Psychological darkness underpins this dark and exciting Western from Mann and Stewart

Director: Anthony Mann

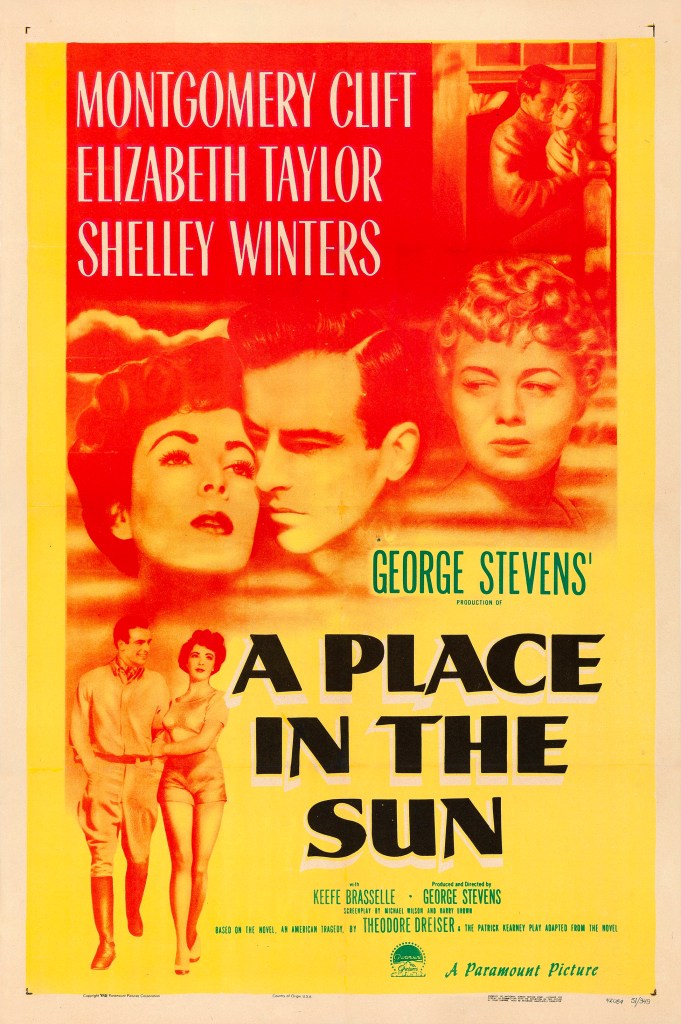

Cast: James Stewart (Lin McAdam), Shelley Winters (Lola Manners), Dan Duryea (‘Waco’ Johnny Dean), Stephen McNally (‘Dutch’ Henry Brown), Millard Mitchell (Frankie ‘High Spade’ Wilson), Charles Drake (Steve Miller), John McIntire (Joe Lamont), Will Geer (Wyatt Earp), Jay C Flippen (Sergeant Wilkes), Rock Hudson (Young Bull), Tony Curtis (Private)

“The Gun That Won the West” was the proud boast of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company of its rifle ((it can fire several shots before reloading unlike normal rifles). As Winchester 73 puts it, such guns built the West and any Indian would give his soul for one. In Anthony Mann’s complex psychological western, it’s also an instrument of death defining a whole era. Winchester 73 follows the path of one ‘perfect’ repeating rifle, won in a shooting competition by Lin McAdam (James Stewart) but stolen from him and passed from hand-to-hand, seeming to curse everyone who touches it to death.

McAdam has his own mission, searching for the man who killed his father, ruthless criminal ‘Dutch’ Henry Brown (Stephen McNally). These two compete for the rifle, in a Tombstone shooting content refereed by legendary Wyatt Earp (Will Geer) whose orders to keep the peace in this town stop the two of them turning guns on each other from the off. Defeated, Dutch steals the rifle (after getting the jump on McAdam), but he doesn’t keep it long as it moves from owner-to-owner. Meanwhile, McAdam purses Dutch, with faithful friend High Space (Millard Mitchell) in tow, encountering war bands, cavalry troops and Lola Manners (Shelley Winters), a luckless woman tied to a string of undeserving men.

Winchester 73 unspools across 90 lean, pacey minutes and gives you all the action you could desire, directed with taut, masterful tension by Mann. It opens with a cracking Hawkesian shooting contest, with the equally matched McAdam and Dutch moving from shooting bullseyes, to dimes out of the sky to through the hoops of tossed rings. Among what follows is a tense face-off between cavalry and Indians, a burning house siege of Dutch’s ruthless ally ‘Waco’ Johnny Dean (Dan Duryea), a high noon shoot-out and a final, deadly, rifle shooting wilderness cat-and-mouse shoot-out between McAdam and Dutch. It’s all pulled together superbly, mixing little touches of humour with genuine excitement.

However, what makes Winchester 73 really stand out is the psychological depth it finds. Audiences were sceptical of James Stewart – George Bailey himself – as a hard-bitten sharp-shooter out for revenge. But Stewart – deeply affected by his war service – wanted a change and Mann knew there was darkness bubbling just under the surface. McAdam is frequently surly, moody and struggles to express warmth and kindness. He can only confess his fondness for High Spade while glancing down at the rifle he’s cleaning and the most romantic gesture he can give Lola is a gun when they are caught up in a cavalry siege, wordlessly suggesting she save the final bullet for herself. McAdam is driven and obsessively focused, stopping for nothing and no-one on his manhunt, a manhunt High Spade worries he is starting to enjoy too much.

And he’s right to worry. In hand-to-hand combat, Stewart lets wildness and savagery cross his face, his teeth gritted, eyes wild. Scuffling for the rifle with Dutch, there is a mania in his eyes that tells us he is capable of killing with his own hands, a look that returns when he later savagely beats the cocky Waco (it’s even more shocking, as Waco’s ruthless skill is well established, before McAdam whoops him like an errant child). Stewart plays a man deeply scarred by the loss of his father, his emotional hinterland laid waste by a burning need for revenge to fill his soul.

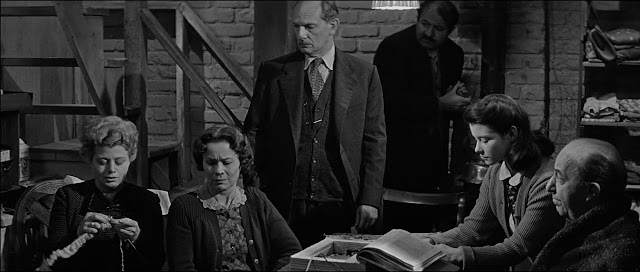

This is the West Winchester 73 sees, one of anger, self-obsession and lies. Seemingly charming trader Joe Lamont (John McIntire, very good) is a shameless card sharp who cheats everyone left-right-and-centre. Waco is perfectly happy to sacrifice his own gang so that he can escape the law – just as he’s perfectly happy to use women and children as human shields and provoke a hapless Steve Miller (Charles Drake), Lola’s luckless lover, into out-matched violence. Steve is hard to sympathise for, having left Lola in the lurch without a second thought when they are caught in the open by a war band (he rides off shouting ‘I’ll get help’ and only returns after finding it by complete fluke).

In this West, a gun is the ultimate symbol. Mann opens every section of the film with a close-up shot of the gun itself, this most prized of possessions, each time in the hands of a new owner. Earp keeps his town strictly gun-free, and both McAdam and Dutch instinctively reach for their holster-less waists when they first meet. (Will Geer does a fine line in avuncular authority as Earp, treated with affectionate patience which becomes quiet fear when he smilingly reveals who he is). The cursed rifle, like Sauron’s ring, seems to tempt everyone and then betray anyone who touches it. Of all its owners, only Dutch and McAdam seem to understand how to use it: and of course, McAdam is the only man with the determination to truly master it.

There isn’t much room for women in all this. Much like the rifle, Lola herself is passed from man-to-man. Played with a gutsy determination by Shelley Winters, she’s first seen thrown out of Tombstone on suspicion of being a shameless floozy, before passing from the useless Steve (who Winters wonderfully balances both affection and a feeling of contempt for) to the psychopathic Waco (few people did grinning black hats better than Dan Duryea). It’s been argued that Lola fills all the traditional female Western roles in one go – hooker, faithful wife, independent women, damsel-in-distress, redemptive girlfriend – and there’s a lot to be said for that. So masculine and violent is this world, women constantly need to re-shape and re-form themselves for new situations.

Fascinating ideas around violence, obsession and sexuality underpin a frontier world where, it’s made clear repeatedly, life is cheap make Winchester 73 really stand out. Led by a bravura performance by James Stewart (who negotiated the first ever ‘points deal’ for this film and made a fortune), with striking early appearances from Rock Hudson (awkwardly as a native chief) and Tony Curtis (as a possibly too pretty cavalry private), it’s both exciting and thought-provoking in its dark Western under-currents