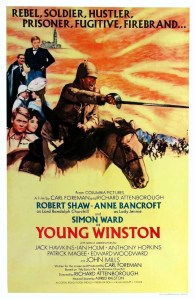

A film of two halves, in more ways than one: the swashbuckling original and its dark sequel

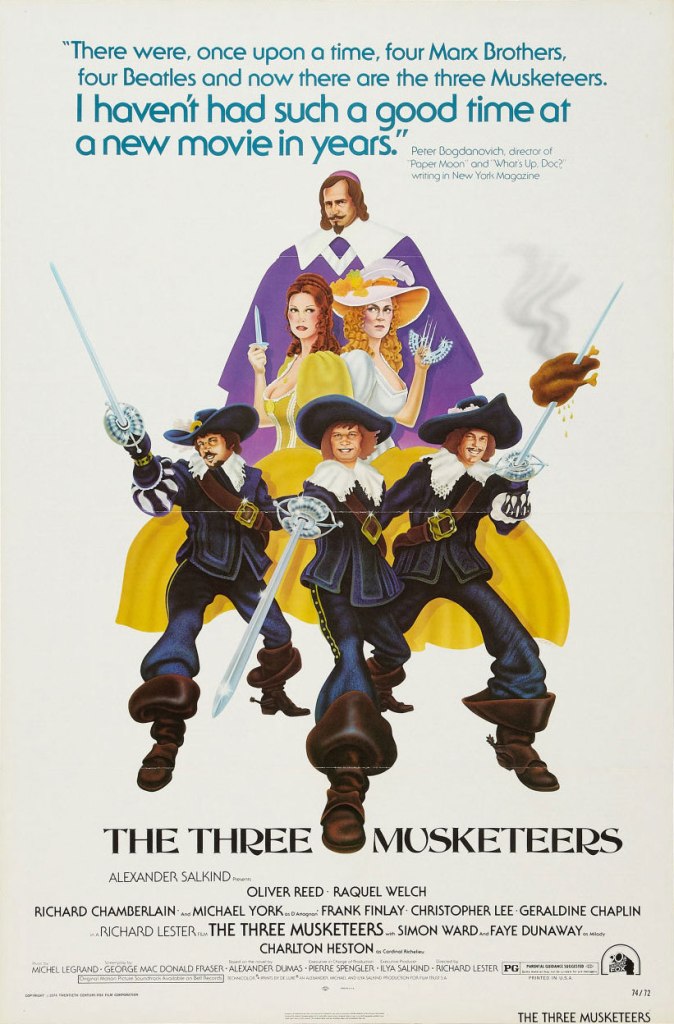

Director: Richard Lester

Cast: Michael York (d’Artagnan), Oliver Reed (Athos), Frank Finlay (Porthos/O’Reilly), Richard Chamberlain (Aramis), Raquel Welch (Constance Bonacieux), Jean-Pierre Cassel (Louis XIII), Geraldine Chaplin (Anne of Austria), Charlton Heston (Cardinal Richelieu), Faye Dunaway (Milady de Winter), Christopher Lee (Count de Rochefort), Simon Ward (Duke of Buckingham), Spike Milligan (Bonacieux), Roy Kinnear (Planchet), Georges Wilson (Captain de Treville)

All for one and one for all! The Three Musketeers is probably the greatest adaptation of Dumas’ rollicking classic, a wonderful mix of swashbuckler, romance and Hellzapoppin comedy, that never takes itself particularly seriously and is crammed with actors having a whale of a time. It’s not quite a send-up, but it’s also not quite a straight re-telling either. Instead, it’s gunning all-out for entertainment – and it succeeds most of the time.

d’Artagnan (Michael York) arrives in Paris in 1625 desperate to join the musketeers. After various adventures along the way – including a rivalry with suavely villainious Rochefort (Christopher Lee) – the impulsive young man forms a friendship (after bumps in the road) with the famed musketeers Athos (Oliver Reed), Porthos (Frank Finlay) and Aramis (Richard Chamberlain). Falling in love with the unhappily married Constance (Raquel Welch), maid to Queen Anne (Geraldine Chaplin), d’Artagnan and his friends are dragged into foiling a plot by the ambitious Cardinal Richelieu (Charlton Heston) to use the ingenious Milady de Winter (Faye Dunaway) to expose the Queen’s infidelity with the Duke of Buckingham (Simon Ward). Will our heroes manage to foil the scheme in time?

The Three Musketeers adapts the first third or so – the most famous and by far the most enjoyable part – of Dumas’ novel. With an irreverent script by Flashman author George MacDonald Fraser, its framed as a rollicking romp with a tongue-in-cheek humour. Richard Lester, famed for his cheeky Beatles comedies (and the film was originally envisaged as a vehicle for the Fab Four), added his trademark scruffy, opportunistic comedy.

The film is awash with muttered asides – many of them well delivered by Roy Kinnear’s exasperated servant Planchet – that are only just picked up by the sound mix. My favourite? d’Artagnan bursting into a room full of guards, yanking a rug with a yell in an attempt to upend them, succeeding only in tearing the corner off it, then immediately jumping out of a window, leaving the bemused guards one of whom plaintively mutters “He’s torn our carpet” – I find this funny on multiple levels, from York’s all-in energy to the stillness of the shot, to the underplayed sadness of the punchline.

Lester’s film is full of long-shot gags – passengers in litters being dropped in a lake, d’Artagnan swinging on a rope to knock someone off a horse, missing and falling in the mud or his jump from a third storey window only to immediately reappear having landed on a (anachronistic) window cleaner cart. While the film does have its moments of drama, danger and intensity, it doesn’t ease up on visual humour, or gags (“This ticket is for one man” “I am one man. This is a servant”). It’s all part of Lester’s plan to make a fast-paced, pantomimic entertainment in which nothing is intended to ever be too serious.

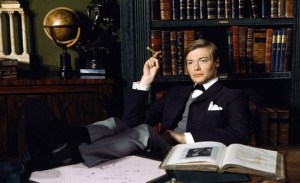

It’s all played with maximum commitment by the cast, all of whom buy into the films’ tone. Michael York leaves very little in the locker-room with a performance full of youthful bravado, lusty hurrahs and naïve, winning eagerness. It’s a very hard balance to get right but he is never overbearing, but provides a relatable, likeable lead. He’s physical commitment to a series of Buster Keaton style gags is also commendable. He sparks a rather sweet romance with Raquel Welch, who is not the world’s strongest actress, but gamely delivers a series of pratfalls as the eternally clumsy Constance.

Around these two, a series of experienced actors delight in larger-than-life roles. Reed brings a surly intensity to Athos, a reminder of how great a career this charisma laden actor could have had. Finlay gives a Falstaffian joie de vivre to Porthos. Chamberlain (with little to do) strikes a gamely romantic figure as Aramis. As the baddies, Heston clearly enjoys subverting his grandiosity as the scheming Cardinal, Dunaway has a kittenish sensuality as Milady and Christopher Lee is so perfect as the debonair Rochefort that his eye patch (unmentioned in Dumas) has become de rigour for every Rochefort performance afterwards.

The Three Musketeers is crammed with swashes being buckled. The sword fights come thick and fast and are all shot in a series of impressive locations (the camera work of David Watkin, design of Brian Eatwell and costumes of Yvonne Blake do a wonderful job creating a sumptuous period setting). At times they do look a little ragged today – producers the Salkinds ran a tight budget, and there are multiple reports of the slightly-under-rehearsed fights leading to near-serious injury (this slapdash preparation would lead to tragic consequences when Roy Kinnear was killed on the belated second sequel 15 years later). But the actors enter into them with a firey commitment (a little too much so in Reed’s case according to the terrified stuntmen) and rumbunctious energy that really sells these as gripping action. They are also give a certain air of peril that gives just enough weight to the film.

The Three Musketeers has moments of dated clumsiness – the bizarely arty slow-mo opening with blurred motion feels totally out-of-keeping with the rest of the film – and not all the jokes land (Spike Milligan in particular is completely over-indulged in the film’s least successful comic moments). Not every performance works – Chaplain in particular is weak as Anne of Austria – and not all the jokes pay off. The musical score by Michael Legrand, catchy as it is, sometimes overeggs the “isn’t this all such fast-paced fun” angle. But the stuff that lands, really does well and there is more than enough fun, action, adventure and rollicking good humour to keep you entertained on a weekend afternoon.

And then there were two (or rather four)

There is always a twist in the tale. At some point while making The Three Musketeers the Salkinds realised they would never get it ready for the Paris premiere. But they could get half the film ready. So, they released that and cheerily announced at the end a sequel was already in the can. Problem was no one had mentioned it to the cast, who discovered they had shot an entire movie for free. A court case exploded, which the Salkinds lost, settling with actors and leading to a new clause being inserted into all contracts for actors preventing such a dodge happening again.

The Four Musketeers covers the second, less famous, much less fun part of Dumas’ novel. Rather like novel, it’s a rambling affair that lacks the compelling narrative thrust (We’ve got to get those diamonds and save the Queen!) which made The Three Musketeers so entertaining. It doesn’t help that its also considerably darker, serious and bleaker as bodies pile up and things get serious.

This makes the sequel a very different beast to the first. Energetic heroism prevented villainy in the first film, but here it often fails . Milady (Faye Dunaway) has sworn revenge and is ordered by Cardinal Richelieu (Charlton Heston) to assassinate Buckingham (Simon Ward). Along the way she kidnaps Constance (Raquel Welch) and seduces d’Artagnan (Michael York) seduced. The Musketeers rescue Constance, fight at La Rochelle and do their best to defend Buckingham – but nothing goes to plan, especially after Athos (Oliver Reed) realises Milady and his criminal ex-wife (thought dead) are one-and-the-same.

The Four Musketeers keeps up the humour, but it is frequently at odds with the darker film it sits in. Gone is the high-paced musical score of Michel Legrand, replaced with a lyrical series of melodies by Lalo Schifrin. It’s telling that Welch – whose comic clumsiness was a large part of the first movie – appears only briefly here. Similarly, Cassell’s shallow monarch (dubbed by Richard Briers) pops up just once, Roy Kinnear’s Planchet isn’t in the first hour and Spike Milligan’s free-wheeling improvisation is missing completely (in that case, no bad thing).

The film feels tonally at odds with the first film and even, at times, with itself. The Three Musketeers was full of sword fights but no deaths – here sword strokes are lethal. As the Musketeers comically bounce around at La Rochelle sight gags abound – but it feels at odds with a film where the death is very real. The more realistic feel means some set pieces – such as Rochefort and d’Artagnan fighting on an inexplicably frozen lake in the height of Summer – become harder to swallow.

Some performers do flourish. Oliver Reed comes into his own as an increasingly dark and vengeful Athos, giving into temptations of shocking revenge. Faye Dunaway laces her role with cold, murderous fury. They have most of the film’s most compelling scenes – but the incredibly dark ending (which involves our heroes actively perpetrating judicial murder with a terrified victim) while loyal to the book, feels far too heavy for a pair of films that started with Buster Keatonish comedy.

The loyalty to the book and the commitment to follow it is partly to blame. There is a reason why most adaptations chuck away this section of the book. It lacks a clear narrative line for emotional connection and is highly episodic. d’Artagnan, in the book, does indeed sleep around after Constance disappears – but when the film requires their relationship to be the emotional heartbeat, is it a good idea to have him jump into bed with two women within days of her disappearance?

Lester announces the more sombre parts by filming them in a very framed, artful way inspired by the old masters, with a static camera and medium shot, reliant on Schifrin’s maudlin music. He’s far more at home with the comic business delivered by Finlay (very good) and Chamberlain (still with nothing to do). At other points he surrenders initiative to legends like Heston (suavely menacing), Lee (whose Rochefort steps up a level in lip-curling contempt) and Dunaway.

The finest thing on display are the sets and the sword fights, which are even more desperate, ragged and violently dramatic than last time (when Rochefort and d’Artagnan stop in one to take a breath, you are not remotely surprised given the total commitment we’ve seen). The action set pieces all look really impressive and staged with confidence and brio. It’s just a shame that much of the rest of the story feels like its being told by a natural comic trying hard to be King Lear, but not able to resist throwing a few gags in. It makes for an entertaining, but tonally messy film that feels it has come from a totally different place than its flawed but fun predecessor.