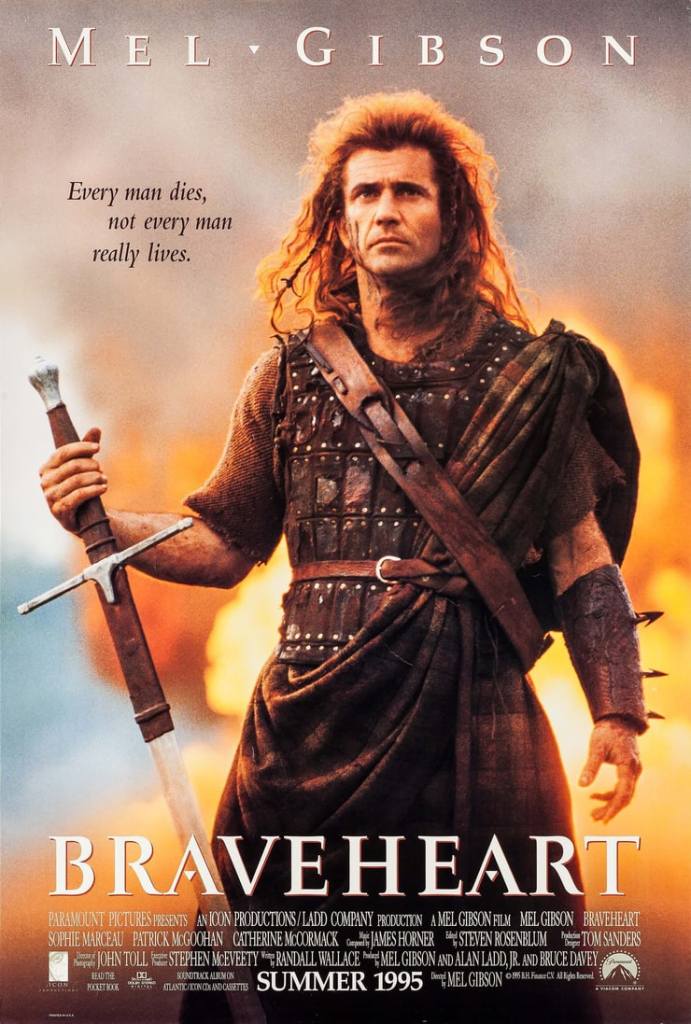

Gibson’s Oscar-winning epic mixes great action and bad everything else – how did it win?

Director: Mel Gibson

Cast: Mel Gibson (William Wallace), Sophie Marceau (Princess Isabelle), Patrick McGoohan (Edward I), Angus MacFadyen (Robert the Bruce), Brendan Gleeson (Hamish), David O’Hara (Stephen), James Cosmo (Campbell), Peter Hanly (Prince Edward), Catherine McCormack (Murron MacClannough), Ian Bannen (Bruce’s Father), Sean McGinley (MacClannough), Brian Cox (Argyle Wallace)

Think back to 1994 and a time when no one really knew who William Wallace was and Mel Gibson was the world’s favourite sexy bad-boy. Because by 1995, William Wallace had become the international symbol of Scottish “Freedom!” and Mel Gibson was an Oscar-winning auteur. Can you believe a film like Braveheart won no fewer than five Oscars, including the Big One? History has not always been kind to it – but then the film was hardly kind to history, so swings and roundabouts.

It’s the late 13th century and Scotland has been conquered by the cruel Edward I (Patrick McGoohan) – a pagan apparently, which just makes you think that Gibson and screenwriter Randall Wallace simply don’t know what that word means. William Wallace (Mel Gibson) saw his whole family killed, but now he’s grown and married to his sweetheart Murron (Catherine McCormack). In secret, as the wicked king has introduced Prima Nocte to Scotland, giving English landlords the right to do as they please with brides on the wedding night. When Murron is killed after a fight to avoid her rape, Wallace’s desire for revenge transforms into a crusade to win Scotland its freedom. A brilliant tactician and leader of men, battles can be won – but can Wallace win the support of the ever-shifting lords, such as the conflicted Robert the Bruce (Angus MacFadyen)? Will this end in freedom or death?

Even in 1995, Braveheart was a very old-fashioned piece of film-making. You can easily imagine exactly the same film being made (with less sex and violence) in the 1950s, with Chuck Heston in a kilt and a “Hoots Mon!” accent. In fact, watching it again, I was struck that narratively the film follows almost exactly the same tone and narrative arc as Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves – with the only difference being if that film had concluded after the Sheriff’s attack on Sherwood Forest with Robin Hood gutted alive in the streets of Nottingham.

This is a big, silly cartoon of a movie, that serves up plenty of moments of crowd-pleasing violence, low comedy, heroes we can cheer and villains we can hiss. Mel Gibson, truth be told, sticks out like a sore thumb with his chiselled Hollywood looks and defiantly modern mannerisms. The film takes a ridiculously simplistic view of the world that categorises everything and everyone into goodies (Wallace and his supporters) and the baddies (almost everyone else).

It’s also far longer than you remember it being. It takes the best part of 50 minutes to build up to Wallace going full berserker after the death of his wife. A later section of the film spends 30 minutes spinning plates between Wallace being betrayed at the Battle of Falkirk and then being betrayed again into captivity (you could have combined both events into one and lost nothing from the film). There is some lovely footage of the Scottish (largely actually Irish) countryside, lusciously shot by John Toll and an effectively Celtic-influenced romantic score by James Horner. In fact, Toll and Horner contribute almost as much to the success of the film as Gibson.

Gibson is by no means a bad director. In fact, very few directors can shoot action and energy as effectively as the controversial Australian. The best bits of Braveheart reflect this. When he’s shooting battles, or fights, or brutal executions he knows what he’s doing. Even if I’d argue that Kenneth Branagh managed to make much less than this look more impressive in Henry V. The battles have an “ain’t it cool” cheek to them, that invites the audience to delight in watching limbs hacked off, horses cut down and screaming Woad-covered warriors ripping through stuffy English soldiers. It’s probably not an accident that the film channels more than a little bit of sport-fan culture into its Scottish warriors.

Where Gibson’s film is more mundane is in almost everything else. The rest of the film is shot with a functional mundanity, mixed with the odd sweeping helicopter shot over the highlands. Its similarities to Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves are actually really strong, from the matey bonhomie of the gang at its heart, its pantomime villain, the moral certainty of its crusades and the fact that Mel Gibson is no more convincing as a 13th-century Scot than Kevin Costner was as Robin Hood. But at least Prince of Thieves knew it was a silly bit of fun. Braveheart thinks it’s got an important message about the immortality of Freedom.

Alongside that, it’s a film that focuses on giving you what you it thinks you want. Gladiator – in many ways a similar film – is a richer and more emotional film, not least because it has the courage to stick to being a film where the hero is faithful to his dead wife and whose triumph is joining her in death. In this film, there are callbacks throughout to the dead Murron – but it doesn’t stop Wallace banging Princess Isabelle, or the film using the same sweeping romantic score to backdrop this as it did for the marriage of Murron and Wallace. What on earth is it trying to say here?

It goes without saying that the real Wallace did not have sex with Princess Isabelle and father Edward III – not least because the real Isabelle was about ten when Wallace died and I’m not sure putting thatin the film would have had us rooting for Wallace. Almost nothing in the film is historically accurate. Wallace is presented as a peasant champion, when he in fact was a minor lord (the film even bizarrely keeps in Wallace travelling Europe and learning French and Latin – a big reach for a penniless medieval Scots peasant). Even the name Braveheart is taken from Robert the Bruce and given to Wallace. The Bruce himself – a decent performance by Angus MacFadyen – is turned into a weak vacillator, under the thumb of his leprous Dad (a lip-smacking Ian Bannen).

The historical messing about doesn’t stop there. Even Wallace’s finest hour, the Battle of Stirling Bridge, is transformed. The film-makers apparently felt the vital eponymous bridge “got in the way” – a sentiment shared by the English, who in reality were drawn into its bottleneck and promptly massacred. Instead we get a tactics free scrap in a field – fun as it is to watch the Scots lift their kilts, it hardly makes sense. The Scots culture in this film is a curious remix of about five hundred years of influences all thrown into one. Prima Nocte never happened. The real Edward II was a martial superstar – but here is a fey, limp-wristed sissy (the film’s attitude towards him stinks of homophobia). Almost nothing in the film actually happened.

But the romance of the film made it popular. It’s a big, crowd-pleasing, cheesy slice of Hollywood silliness. The sort of film where Wallace sneaks into someone’s room at the top of a castle riding a freaking horse and no-one notices. It tells a simple story in simple terms, using narrative tricks and rules familiar from countless adventure films since The Adventures of Robin Hood. It looks and sounds great, enough to disguise the fact that it isn’t really any good. Because it has a sad ending, scored with sad music, it tricked enough people to think it had depth and style. In fact is a very mediocre film, hellishly overlong, that turns history into a cheap comic book. It remains in the top 100 most popular films of all time on IMDB. It’s about as likely an Oscar winner as 300.