Bertolucci’s bloated, self-indulgent and simplistic film is a complete mess

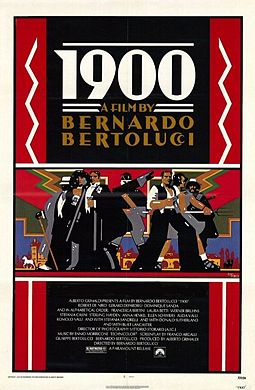

Director: Bernardo Bertolucci

Cast: Robert De Niro (Alfredo Berlinghieri), Gerard Depardieu (Olmo Dalco), Dominique Sanda (Ada Fiastri Paulhan), Donald Sutherland (Attila Mellanchini), Laura Betti (Regina), Burt Lancaster (Alfredo Berlinghieri the Elder), Stefania Sandrelli (Anita Foschi), Werner Bruhns (Ottavio Berlinghieri), Stefania Casini (Neve), Sterling Hayden (Leo Dalco), Francesca Bertini (Sister Desolato), Anna Henkel (Anita the Younger), Ellen Schwiers (Amelia), Alida Valli (Signora Pappi)

After The Conformist and Last Tango in Paradise, Bertolucci could do anything he wanted. Unfortunately, he did. Perhaps the saddest thing about 1900 is that you could watch The Conformist twice with a decent break in-between during the time it would take you to watch it– and get a much richer handle on everything 1900 tries to do. Bertolucci went through a struggle to get his 315-minute cut released: perhaps the best thing that could have happened would have been if he had lost. Not only would the film be shorter, but it would be remembered as a lost masterpiece ruined by producers, rather than the interminable, self-indulgent mess we ended up with.

1900 – or Twentieth Century to literally translate its title Novecento – follows the lives of two very different men. Born minutes apart in 1901, Alfredo (Robert De Niro) is the grandson of the lord of the manor (Burt Lancaster), while Olmo (Gerard Depardieu) is the grandson of Leo (Sterling Hayden), scion of a sprawling dynasty of peasants. They grow up as friends, Olmo becomes a socialist and Alfredo an indolent landlord and absent-minded collaborator with the fascists, embodied by his psychopathic land agent Attila (Donald Sutherland). Their small community becomes a symbol of the wider battle between left and right in Italy.

In many ways 1900 is an epic only because it is extremely long and beautifully shot in the Bologna countryside by Vittorio Storaro. In almost every sense it fails. It offers nominal scale in its timeline, but its attempt to become a sweeping metaphor for Italy in the twentieth century falls flat and it focuses on a small community of simple characters, many of whom are ciphers rather than people. All of Bertolocci’s communist sympathies come rushing to the fore in a film striking for its political simplicity. It never convinces in its attempt to capture in microcosm the forces that divided Italy between the two world wars, nor invests any of its characters with an epic sense of universality.

Instead Bertolucci presents a world of obvious questions and easy answers. Every worker is an honest, noble salt-of-the-earth type, working together in perfect harmony to fight for rights. Every single upper-class character is an arrogant, selfish layabout, caring only about their back-pockets and the easy life. Bertolucci suggests fascism only arose in Italy as a means for the rich to control the poor, and never allows for one moment the possibility that any working-class person was ever tempted to take their side. It never rings true. (Bertolucci skips a huge chunk of the fascist 30s and 40s, possibly because this fantasy would be impossible to sustain if he actually focused on the history of that era.)

Bertolucci uses his two protagonists to make painfully on-the-nose comparisons between working class and rich with De Niro’s weak-willed Alfredo always found wanting compared to Depardieu’s Olmo. Even as children, Olmo is braver, stronger and smarter. Olmo has the guts to lie under the moving trains (Alfredo runs), Olmo stands up for what he believes in (Alfredo looks away), Olmo puts others first Alfredo whines about his own needs. Hell, Olmo even has a bigger cock than Alfredo (something they discover comparing penises as children and re-enforced when as young men they share an epileptic prostitute and she ‘tests’ them both).

The upper classes hold all the power but can do nothing without the working class. During the 1910s, a strike by the workers on the Berlinghieri leaves the clueless rich unable to even milk their moaning cows (they buy milk instead). Sterling Hayden’s peasant patriarch is a manly inspiration to all, while Lancaster’s increasingly shambling noble is literally and metaphorically impotent (Lancaster’s role is like a crude commentary on his subtle work in The Leopard). At one point he even pads around barefoot in horseshit to hammer home his corruption. (Incidentally this is the only film where you’ll ever see a horse’s anus being massaged on camera to produce fresh shit to be thrown at a fascist.)

For the rich, fascism is the answer. Continuing to shoot fish in a barrel, Bertolucci scores more easy hits by presenting our prominent fascist as an out-and-out psychopath. Played with a scary relish by Sutherland – in the film’s most compelling performance – no act of degradation is too far for Attila. Along with his demonic partner-in-crime Regina (a terrifyingly loathsome Laura Betti), he routinely carries out acts of violence, horrific murder and child-abuse, even literally headbutting a cat to death while ranting about the evils of socialism.

The poor meanwhile are all good socialists. Olmo, decently played by Depardieu, and his wife Anita (an affecting Stefania Sandrelli) rally the workers to stand against charging cavalry and protect their rights. Bertolucci even has Depardieu flat-out break the fourth wall for a closing speech, spouting simplistic platitudes direct to camera about the inherent wickedness of the landowner. Depardieu at least seems more comfortable than De Niro among this Euro-pudding (every actor comes from a different country and the soundtrack is a mismatch of accents and dubbing, not least Depardieu himself). Rarely has De Niro looked more uncomfortable than as the empty Alfredo, a role he fails to find any interest in, like the rest of the actors never making him feel like more than a device.

Bertolucci, stretching the run-time out, also embraces numerous tiresome excesses. Rarely does more than 20 minutes go by without a sex scene or a sight of someone’s breasts or sexual organs. From children comparing penises, to Depardieu performing oral sex on Sandrelli (just outside a socialist meeting), to De Niro and Depardieu getting hand-jobs from a prostitute, to Sanda dancing naked and high on cocaine or the revolting exploits of Attila and Regina, nothing is left to the imagination. As each goes on and on Bertolucci ends up feeling more like a naughty boy than an artist, so praised for his sexual licence in Last Tango that he feels more is always more. The excess doesn’t stop with sex either: at one point a worker silently cuts his ear off in front of a landowner to make a point about his stoic nobility.

1900 eventually feels like you’ve stumbled into a student debating club, where a privileged student drones on at great length about the evils of the rich, while quaffing another glass of champagne. It has moments of cinematic skill – some of its time jump transitions, in particular a train passing through a tunnel in one time and emerging at another, are masterful – but it’s all crushed under its self-indulgence. From its length to its sexual and violence excess, to its crude and simplistic politics delivered like a tedious lecture, everything is crushed by its never-ending self-importance.