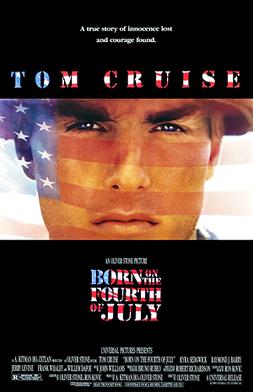

Passionate polemic against Vietnam, with a committed central performance – tough, angry viewing

Director: Oliver Stone

Cast: Tom Cruise (Ron Kovic), Willem Dafoe (Charlie), Kyra Sedgwick (Donna), Raymond J Barry (Eli Kovic), Jerry Levine (Steve Boyer), Frank Whaley (Timmy), Caroline Kava (Patricia Kovic), Cordelia Gonzalez (Maria Elena), Ed Lauter (Commander), John Getz (Major), Michael Wincott (Veteran), Edith Diaz (Madame), Stephen Baldwin (Billy), Bob Gunton (Doctor)

Ron Kovic and Oliver Stone shared the feelings of many of their generation: a deep and abiding feeling of betrayal about the war they were sold in Vietnam. Kovic entered Vietnam a passionate true-believer in the cause; he left a traumatised veteran, paralysed from the waist-down, facing a difficult journey of guilt and discovery that would lead him into a career of anti-war activism. Stone too left Vietnam, wounded and affected with PTSD. The two had collaborated on a screenplay of Kovic’s autobiography in the 70s, before funding fell through: Stone vowed he would make the film when he had the power: the success of Platoon and Wall Street gave him that.

It’s not a surprise, considering the understandable passion that went into it, that Born on the Fourth of July is a polemic. You can argue it’s a heavy-handed and virulent one: but then it’s hard to argue with the catastrophic impact over a decade of American foreign policy decisions had on generations across several countries. Could it have been anything else? Born can be an uncomfortable and relentless watch, and subtlety (as is often the case even in Stone’s best work) can be hard to spot. But is that a surprise when the whole film feels like a ferocious, cathartic cry of pain?

It follows a mildly fictionalised version of Kovic’s life (Kovic’s willingness to adapt his life, drew some fire at the time – particularly as he was considering a run for Congress) starting with his childhood, through his teenage enlistment, the shocking horror of Vietnam, his limited recovery in under-funded veteran hospitals, his growing discomfort with the attempt by some (including his passionately conservative mother) to celebrate sacrifices he increasingly feels were misguided and wrong, culminating in his joining the ranks of the same long-haired protestors he spoke of disparagingly earlier.

Through it all, Kovic is played with a searing intensity by Tom Cruise. Cruise was a controversial choice – seen as little more than a cocky cocktail juggling, jet piloting, superstar (despite measured, subtle turns in The Color of Money and Rain Man). It feels a lot more logical today, now that Cruise’s Day-Lewis commitment to projects is well-known. It’s a raw, open and vulnerable performance with Cruise expertly inverting the cocksure confidence of his persona (and the earlier scenes), to portray a man deeply in denial at his injuries (internal and external), with resentment, anger and self-loathing increasingly taking hold of him.

Kovic is a man who never gives up: be that a misguided (and in the end almost fatal) attempt to defy medical advice that he will never walk again, to embracing the anti-war cause with the same never-say-die attitude he signed up to the military with. What Stone and Cruise bring out, is the huge cost to Kovic of working out the fights worth having: from his student days training days on hand for a wrestling bout he loses, to is military career, to activism, it’s a long, difficult journey.

It’s a performance that understands the crippling burden of guilt. Cruise commits to Kovic’s rage, but always keeps track of the vulnerable, damaged, scared soul underneath. He never allows us to forget this is a man eating himself up, not with resentment at his injury, but guilt at his actions in Vietnam – from being part of a mission that pointlessly machine-gunned women and children, to his own accidental shooting of a fellow marine. As you would expect from Stone, Born’s view of Vietnam is bleak: pointless, disorganised missions, led from the rear by incompetent or uncaring officers, where the only victims are innocent civilians or GIs.

That’s perhaps the key about Born. Kovic is not motivated primarily by his injuries. Those are the results of the risks he chose and, to a certain degree, he accepts them. What motivates him is guilt: throughout he is haunted by the crying of the Vietnamese baby he was ordered to leave in the arms of its deceased mother while also struggling to accept his guilt at his friendly fire killing. These feelings fuel his self-loathing, and his anger rightly develops against the lies he was told that led him to commit those acts.

Stone’s film is unrelentingly critical of the mythologising of armed American intervention, and the assumption (often parroted by those who stay at home) that it can never be anything other than completely righteous. It’s a society where (as happens in the film’s opening) children play at soldiers, watch parades of veterans (the young Kovic fails to clock the flinching of these veterans – one played by the real Kovic – at rifle fire, seeing only what he wants to see) and, as young men, are sold tales of duty, sacrifice and heroism. Kovic is too young and fired-up to notice the reluctant pain of his veteran dad (a superbly low-key Raymond J Barry), clearly struggling with his own trauma.

Much as the film paints one of Kovic’s friends in a negative light – like a young Gecko he heads to college, states all this talk of Communism conquering the world is propaganda bullshit and sets up a burger chain where he brags about fleecing the customers and groping the female staff – it also can’t but admit that when it came to Vietnam, he was right. Similarly, Stone is critical of Kovic’s ambitious, apple-pie Mom (Caroline Kava, in a performance of infuriatingly smug certainty) who won’t hear a word against the war and demands achievement from her son, constantly stressing it must have been worth it.

It’s not a surprise one of Born’s most cathartic moment is when Kovic – Cruise’s performance hitting new heights of unleashed resentment – rails late-at-night at his Mom, calling out her upbringing of unquestioning patriotism and saintly conformity as nothing but an ocean of bullshit. It’s an outpouring that has been welling up since his return, looking for the right direction: snapping at protestors, doctors, his younger brother who dares to oppose the War. Born is about a man coming to terms with why he is so angry and finding the appropriate target: and it becomes the system that sent him on this journey, starting with his mother and onto his own government.

This would be the government that provides shabby hospitals, full of broken-down equipment, whacked out attendants and overworked, underqualified doctors. Stone’s camera pans along wards piled with rubbish and rats. The conditions here are, in many ways, worse than the Mexican villa where Kovic finds himself struggling to re-adjust, surrounded by other paralysed veterans (among them Willem Dafoe, as a seemingly mentor-like figure with uncurdled rage just below the surface). Stone’s film never once loses its righteous fury at how a generation was let down by its leaders on every level.

So it’s not surprising Born is a fiercely polemic work. And, yes, that does sometimes reduce its interest and make it an unrelentingly grim watch (Stone isn’t interested in putting any other side of the argument in here). But it’s extremely well made (Robert Richardson’s excellent photography uses tints of red, white and blue at key points to brilliantly stress mood) and you can feel the heart Stone (who won a second directing Oscar for this) put into it. Its impact comes down to how much you engage with the passionate, furious argument its making: connect with it and it’s a very powerful film.