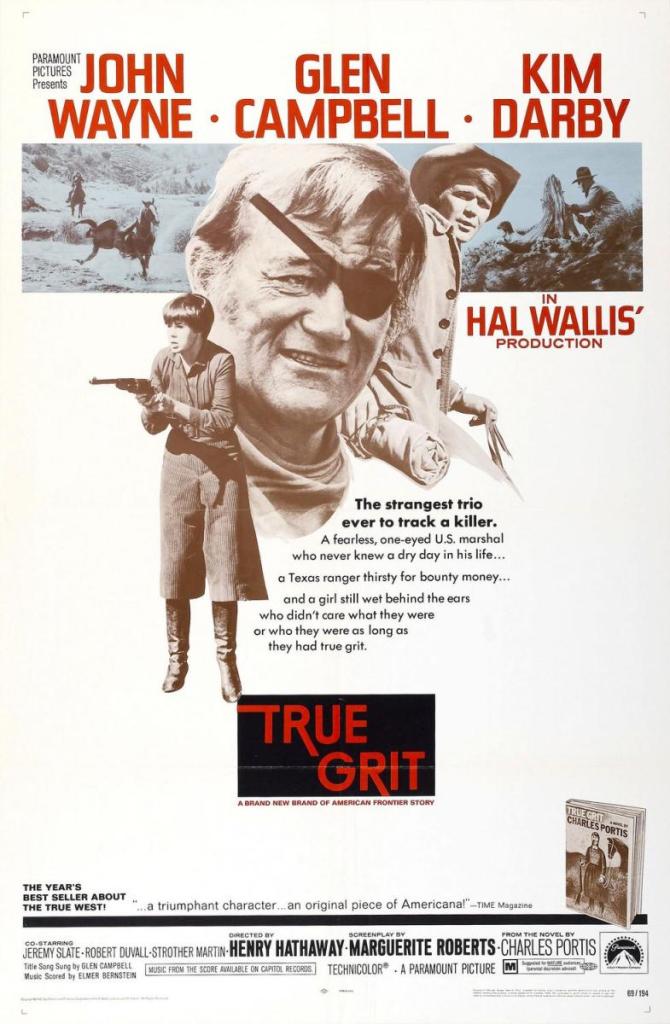

The Duke wins an Oscar in this solid Western (already old-fashioned in 1969) put together with a professional solidity

Director: Henry Hathaway

Cast: John Wayne (Reuben “Rooster” Cogburn), Glen Campbell (La Boeuf), Kim Darby (Mattie Ross), Jeremy Slate (Emmett Quincy), Robert Duvall (Lucky Ned Pepper), Dennis Hopper (Moon), Alfred Ryder (Goudy), Strother Martin (Colonel Stonehill), Jeff Corey (Tom Chaney), John Fiedler (Daggett)

By 1969 John Wayne had been pulling his six shooters against rascals and rapscallions for thirty years, ever since making one of the all-time great entries in Stagecoach. He’d been an American icon, box-office gold and practically the Mount Rushmore of Hollywood. What he never really had was recognition that, underneath the drawl, he was a fine actor who knew his business. He’d only had the single Oscar nomination in 1949, so by 1969 there was a sentimental urge to correct that – especially since illness had already seen the Duke (one of the first major stars to be open and frank about his cancer and urge others to get checks) lose a lung a few years previously.

And correct that they did, as Wayne beat out two respected thespians (the perennially unlucky Burton and O’Toole) as well as the whipper-snapper stars of Midnight Cowboy (the sort of cowboy film the Duke would never even consider making!) to scoop the Best Actor prize for taking a character-role lead (all Wayne roles are lead roles) in True Grit. Wayne was “Rooster” Cogburn, a hard-drinking but hard-riding, always-gets-his-man US Marshal, hired by Mattie Ross (Kim Darby) the teenager daughter of a murdered father to track down his killer Tom Chaney (Jeff Corey). Rooster develops an avuncular relationship with Mattie, despite his penchant to get pissed and (of course!) eventually proves he has the ‘true grit’ that made Mattie hire him in the first place.

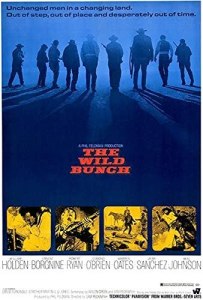

True Grit is a traditional yarn, directed with a smooth competence (but lack of inspiration) by Henry Hathaway. It must have felt quite a throwback in 1969: you could imagine it pretty much would have been shot-for-shot identical if it had been filmed in 1949 (especially since Wayne had been playing the veteran since at least Fort Apache). Compared to other major Westerns made that year – Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and, especially, the grim nihilism of The Wild Bunch – True Grit looks like the cosiest film imaginable. It even shies away from the book’s ending where Mattie loses an arm after a snake bite (something the, frankly superior, Coen Brother’s remake would not do 40 years later).

It does feel odd to see Wayne, that bastion of old-school Hollywood, sharing the screen with New Hollywood icons like Dennis Hopper (playing a yellow-bellied squealer at the baddies hideout) and Robert Duvall (a belated villain, looking uncomfortable in this genre saddle-flick as a bad-to-the-bone gang leader). But Hathaway makes sure it’s The Duke’s show. Which it is from start-to-finish.

Rooster isn’t really a stretch for Wayne. Compared to his work in The Searchers and Red River, Cogburn is a cosy and straight-forward hero, a straight-shooter who always holds to his word. But it’s a perfect showpiece for his charisma. Wayne shows a decent comic-timing (he has a nice line in deadpan reactions, particularly when he meets Mattie’s famed lawyer Daggett for the first time, discovering far from the imposing figure he imagined he’s actually the mousy John Fiedler) and there’s just a little hint of lonely sadness in Rooster as he talks about the family who left him or the homes he’s never known.

Wayne also has a lovely chemistry with Kim Darby, the relationship flourishing in a rather sweet big-brother-“little sister” (as Rooster calls her) way. Although of course it takes time to form: Rooster spends most of the first half of the film trying his best to shrug her off so he can hunt down the gang Tom Chaney runs with (and collect the bounty for them) unencumbered. The two of them form a tenuous alliance with Texas Ranger La Bouef, who is far keener to deliver Chaney to another state for a higher bounty than that offered for the killing of Mattie’s father.

La Bouef is played with try-hard gameliness by singer Glen Campbell, largely hired to commit him to singing the film’s best-selling theme tune. To be honest, he makes for a weak third wheel – but it’s hard not to hold it against Campbell when he charmingly later said he’d “never acted in a movie…and every time I see True Grit I think my record’s still clean!”. Far better is Kim Darby, who gives a spunky tom-boyish charm to the shrewd and persistent Mattie who is far too-smart to either by cheated by short-changing landlords or to be ditched from the trail by Rooster and La Bouef.

It’s Wayne’s film though, and a final act face-off with the villains shows that there were few people better with a gun on screen (his one-handed shotgun twirling reload while riding a horse is surely the envy of Schwarzenegger’s similar move in Terminator 2). The whole enterprise is carefully framed to showcase Wayne and he rises to the occasion. Think of it like that, and it hardly matters that Hathaway offers uninspired work behind the camera and fails to provide either any moments of visual interest or dynamism (or work effectively with the weaker actors).

True Grit is an entertaining, second-tier Wayne film, lifted by his charisma and enjoyment for playing a larger-than-life gravelly cool-old-timer and cemented in history by his reward with that sparkling gold bald man. Compared to other Westerns – both before and at the time – it’s traditional, straight-forward and unchallenging. But it’s fun, has some good jokes and offers decent action. And it’s a reminder that no one did this sort of thing better than the Duke.