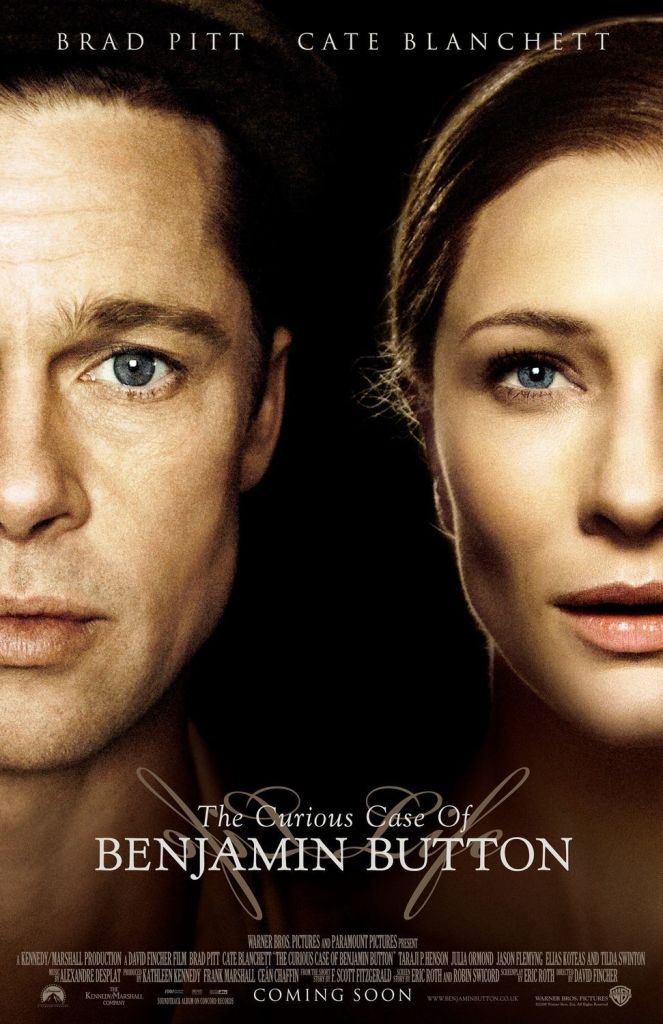

Ageing, romance and sentiment in Fincher’s handsome shaggy dog story

Director: David Fincher

Cast: Brad Pitt (Benjamin Button), Cate Blanchett (Daisy Fuller), Taraji P Henson (Queenie), Julia Ormond (Caroline Button), Jason Flemyng (Thomas Button), Elias Koteas (Monsieur Gateau), Tilda Swinton (Elizabeth Abbott), Mahershala Ali (Tizzy Weathers), Jared Harris (Captain Mike Clark)

As the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918 strikes, a baby boy is born. A baby boy unlike any other, with the appearance and illnesses of a very old man. Discarded by his horrified father (Jason Flemyng), the boy is adopted by Queenie (Taraji P Henson), caretaker of a nursing home. There it becomes clear he is growing backwards: the older he gets, the younger he appears. Young Benjamin will eventually grow into Brad Pitt and spend his life watching those around him grow ever older as he grows ever younger. Most joyful, and painful, of all being his childhood friend Daisy (Cate Blanchett), the woman he will love his whole life.

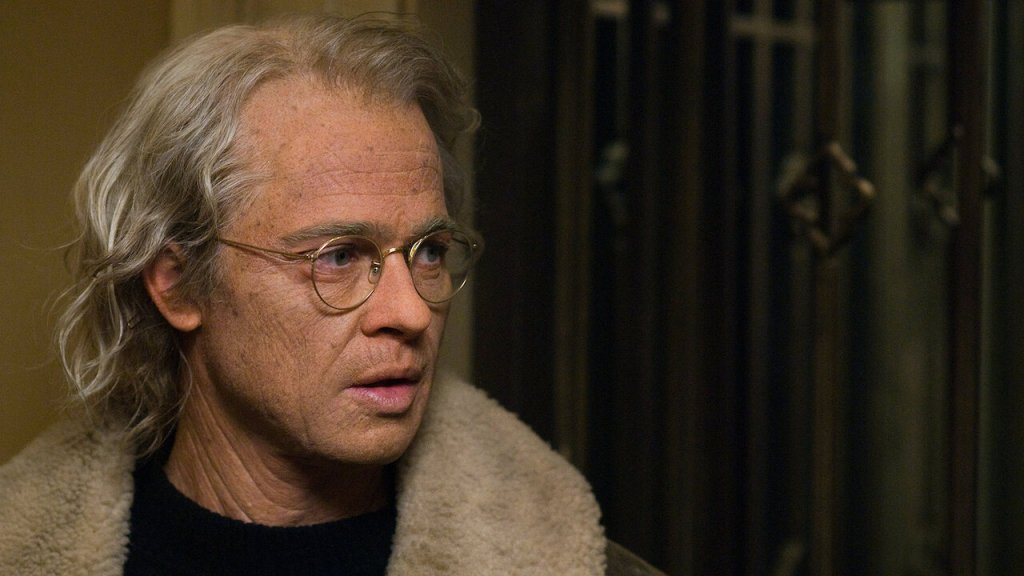

Fincher’s film is a strange beast. A huge technical triumph, that uses cutting edge special effects and astonishing make-up to age – in both directions – Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett throughout the course of the film (both taken from extreme old age to face-lifted youth), it’s also a whimsical shaggy dog story with elements of a fairy tale that does very little with its astonishing concept other than pepper the script with easily digestible homilies about the purity of the simple life, as if screenwriter Eric Roth was still gorging on the same box of chocolates from which he plucked Forrest Gump.

TCCoBB has a lot going for it: you can see why it was coated with technical Oscars. The ageing and deageing special effects are skilfully and even subtly done, the recreation of a host of periods – from the 1910s to the 1990s and beyond – flawlessly detailed. Claudio Miranda’s photography uses a host of film stocks – from sepia, to scratchy home movie footage style, to luscious technicolour beauty – to reflect time and era constantly. The assemblage of the film has been invested with huge care and attention and, despite its great length, Fincher cuts together (with Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall) an episodic film that manages to keep its momentum and drive going.

Also, it’s a far less vomit-inducing spectacle than the manipulative stylings that coat Forrest Gump. This is in part to Brad Pitt’s restrained and contemplative performance in the lead role: Pitt underplays with surprising effectiveness, capturing Benjamin’s “come what may” attitude and eagerness to go with the flow of the opportunities life offers him. He delivers the narration with an authority just the right side of portentous (for all his rather flat, uninteresting voice) and skilfully manages to invest his body with a physicality quite contrary to his physical appearance (his old body moves with a young man’s casualness, while his younger form carries a slightly world-weary hesitancy).

Benjamin’s mantra becomes one of living your life just as suits you best, not as others expect you to and never worrying about leaving it too late to take chances or make changes. Or at least something like that. To be honest, the weakest part by far of TCCoBB is the lightness and breeziness of its thematic impact. I’ve seen this film three times and, other than a slightly charming shaggy dog story, I’m not quite sure what point it is trying to make – other than straining for a star-cross’d romantic sadness.

This feels like a missed opportunity because there is so much that could be explored here. The film is a nearly unique opportunity to explore how much age – either physical or mental – defines us. A chance to see how our perceptions of a person are shaped as much by what they look like or how they sound, as by who they are. What sort of different perspective on humanity might Benjamin have? How might those around him evaluate, their own lives as they see this him getting younger?

Questions such as these are not touched, the film settling for Benjamin’s whimsical, first-do-no-harm philosophy crossed with a sort of saintly non-interference. The closest it gets to dealing with this is in Benjamin’s friendship and later relationship with Daisy. Old/young Benjamin is told off by Daisy’s grandmother for being a dirty old man, when they first met as children (or old man in his case). Later their lives will drift together and apart, until they form a relationship when both are “the same age” physically. But the film shirks really exploring the implications of this – and outright flees the idea of Benjamin as an increasingly younger man in a romantic relationship with an increasingly older Daisy.

Instead, it settles all too often for easy lessons, comforting parables and charming little vignettes. Benjamin grows up cared for by his adopted mother Queenie (an engaging, if straight forward, performance by Taraji P Henson) – but in the sort of 1920s New Orleans where a racial epithet is never even whispered. He travels the world with Jared Harris’ (rather good) salty sea-dog, falling in love briefly with Tilda Swinton’s lonely champion swimmer turned society wife. He reconnects happily with his father (after all it’s much easier to live a life of free choice if you are the heir to a massive button factory empire). Idyllic 1960s love hits Daisy and Benjamin – a brief shot of a cruise missile taking off is the only reference to those troubled times we see.

It’s all very easy, romantically toned, sweet and easily digestible. Even writing it down highlights how these are charming, eccentrically tinged, vignettes. All events and experiences come together with a vague “lessons learned” impact, as old Benjamin regresses into a teenager, a child and then an infant. But it could have been so much more. A real study of what makes us human, a real look at how events and perspectives define us. It isn’t. Heck, other than watching Pitt travel handsomely around the world on a motorbike in a late montage, we don’t really get much of a sense of how being young/old may impact him.

Which isn’t to say it’s not enjoyable. It all proceeds with a great deal of charm and love, much of which has clearly been invested in every inch of its making. The acting from (and chemistry between) Pitt and Blanchett is very effective. But it feels like a slightly missed opportunity, a film that settles for being a warm, reassuring cuddle when it could have sat you down and helped you understand your life. For all its slight air of importance, it’s a crowd-pleasing, if slightly sentimental, film.