|

Max von Sydow carries a heavy burden in Steven’s far-from The Greatest Story Ever Told |

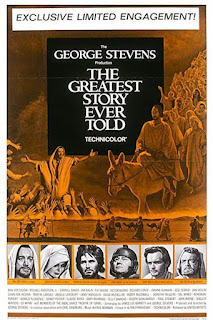

Director: George Stevens

Cast: Max von Sydow (Jesus), Dorothy McGuire (The Virgin Mary), Charlton Heston (John the Baptist), Claude Rains (Herod the Great), José Ferrer (Herod Antipas), Telly Savalas (Pontius Pilate), Martin Landau (Caiaphas), David McCallum (Judas Iscariot), Donald Pleasance (“The Dark Hermit”), Michael Anderson Jnr (James the Less), Roddy McDowell (Matthew), Gary Raymond (Peter), Joanna Dunham (Mary Magdalene), Ed Wynn (Old Aram), Angela Lansbury (Claudia), Sal Mineo (Uriah), Sidney Poitier (Simon of Cyrene), John Wayne (Centurion)

You could make a case to prosecute The Greatest Story Ever Told under the Trade Descriptions Act. In a world where we are blessed (cursed?) with a plethora of Biblical epics, few are as long, worthy, turgid or dull as George Stevens’ misguided epic. Just like Jesus in the film is plagued by a Dark Hermit representing Satan, did Stevens have a wicked angel whispering in his ear “More wide shots George, and even more Handel’s Messiah. And yes, The Duke is natural casting for a Roman Centurion…”. The Greatest Story Ever Told has some of the worst reviews Christianity has ever had – and it’s had some bad ones.

The plot covers the whole life of the Saviour so should be familiar to anyone who has ever seen a Gideon’s Bible. It was a passion project for Stevens, who spent almost five years raising the cash to bring it to the screen. When he started, the fad for self-important Biblical epics was starting to teeter. When it hit the screen, it had flat-lined. It didn’t help that The Greatest Story Ever Told was first released as an over four-hour snooze fest, laboriously paced, that managed to drain any fire or passion from one of (no matter what you believe) the most tumultuous and significant lives anyone on the planet has ever led. The film was cut down to about two hours (making it incomprehensible) and today exists as a little over three-hour epic that genuinely still feels like it’s four hours long.

Stevens gets almost nothing right here whatsoever. Self-importance permeates the entire project. The film cost $20million, double the largest amount the studio had ever spent. Ordinary storyboards were not good enough: Stevens commissioned 350 oil paintings (that’s right, an entire art gallery’s worth) to plan the picture (which probably explains why the film feels at times like a slide show of second-rate devotional imagery). The Pope was consulted on the script (wisely he didn’t take a screen credit). Stevens decided the American West made a better Holy Land than the actual Holy Land, so shot it all in Arizona, Nevada and California. It took so long to film, Joseph Schildkraut and original cinematographer William C Mellor both died while making it, while Joanna Durham (playing Mary Magdalene!) became pregnant and gave birth. Stevens shot 1,136 miles of film, enough to wrap around the Moon.

There’s something a little sad about all that effort so completely wasted. But the film is a complete dud. It’s terminally slow, not helped by its stately shooting style where the influence of all those paintings can be seen. Everything is treated with crushing import – Jesus can’t draw breath without a heavenly choir kicking in to add spiritual import to whatever he is about to say. Stevens equates grandeur with long shots so a lot of stuff happens in the widest framing possible, most ridiculously the resurrection of Lazarus which takes place in a small part of a screen consumed with a vast cliff panorama. Bizarrely, most of the miracles take place off-screen, as if Stevens worried that seeing a man walk on water, feed the five thousand or turn water into wine would stretch credulity (which surely can’t be the case for a film as genuflecting as this one).

What we get instead is Ed Wynn, Sal Mineo and Van Heflin euphorically running up a hilltop and shouting out loud the various miracles the Lamb of God has bashfully performed off-screen. Everything takes a very long time to happen and a large portion of the film is given over to a lot of Christ walking, talking at people but not really doing anything. For all the vast length, no real idea is given at all about what people were drawn to or found magnetic about Him. It’s as if Stevens is so concerned to show He was better than this world, that the film forgets to show that He was actually part of this world. Instead, we have to kept being told what a charismatic guy He is and how profound His message is: we never get to see or hear these qualities from His own lips.

For a film designed to celebrate the Greatest, the film strips out much of the awe and wonder in Him. It’s not helped by the chronic miscasting of Max von Sydow. Selected because he was a great actor who would be unfamiliar to the mid-West masses (presumably considered to be unlikely to be au fait with the work of Ingmar Bergman), von Sydow is just plain wrong for the role. His sonorous seriousness and restrained internal firmness help make the Son of God a crushing, distant bore. He’s not helped by his dialogue being entirely made-up of Bible quotes or the fact that Stevens directs him to be so stationary and granite, with much middle-distance staring, he could have been replaced with an Orthodox Icon with very little noticeable difference.

Around von Sydow, Stevens followed the norm by hiring as many star actors as possible, some of whom pop up for a few seconds. The most famous of these is of course John Wayne as the Centurion who crucifies Jesus. This cameo has entered the realms of Filmic Myth (the legendary “More Awe!”exchange). Actually, Stevens shoots Wayne with embarrassment, as if knowing getting this Western legend in is ridiculous – you can hardly spot Wayne (if you didn’t know it was him, you wouldn’t) and his line is clearly a voiceover. In a way just as egregious is Sidney Poitier’s wordless super-star appearance as Simon, distracting you from feeling the pain of Jesus’ sacrifice by saying “Oh look that’s Sidney Poitier” as he dips into frame to help carry the cross.

Of the actors who are in it long enough to make an impression, they fall into three camps: the OTT, the “staring with reverence” and the genuinely good. Of the OTT crowd, Rains and Ferrer set the bar early as various Herods but Heston steals the film as a rug-chested, manly John the Baptist, ducking heads under water in a Nevada lake, bellowing scripture to the heavens. Of the reverent, McDowell does some hard thinking as Matthew, although I have a certain fondness for Gary Raymond’s decent but chronically unreliable Peter (the scene where he bitches endlessly about a stolen cloak is possibly the only chuckle in the movie).

It’s a sad state of affairs that the Genuinely Good actors all play the Genuinely Bad characters – poor old Jesus, even in the story of his life the Devil gets all the best scenes. That’s literally true here as Donald Pleasence is head-and-shoulders best-in-show as a softly spoken, insinuating but deeply sinister “Dark Hermit” who tempts Jesus in the wilderness and then follows Him throughout the Holy Land, turning others against Him. Also good are David McCallum as a conflicted Judas, Telly Savalas as weary Pilate (he shaved his head for the role, loved the look and never went back) and Martin Landau, good value as a corrupt Caiaphas (“This will all be forgotten in a week” he signs the film off with saying).

That’s about all there is to enjoy about a film that probably did more to reduce attendance at Sunday School than the introduction of Sunday opening hours and football being played all day. A passion project from Stevens where he forgot to put any of that passion on the screen, it really is as long and boring as you heard, a film made with such reverent skill that no one seemed to have thought about stopping and saying “well, yes, but is it good?”. I doubt anyone is watching it up in Heaven.