Unsettling dread abounds in this beautiful, terrifying collection of ghost stories

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Cast: The Black Hair – Rentarō Mikuni (Samurai), Michiyo Aratama (First wife), Misako Watanabe (Second wife); The Woman of the Snow – Tatsuya Nakadai (Minokichi), Keiko Kishi (Yuki-Onna); Hoichi the Earless – Katsuo Nakamura (Hoichi), Tetsurō Tamba (Warrior), Takashi Shimura (Head priest); In a Cup of Tea – Osamu Takizawa (Author), Noboru Nakaya (Shikibu Heinai), Seiji Miyaguchi (Sekinai)

What is horror? For many people, it’s guts and gore. But I’ve always found far more unsettling the creeping terror of the unnatural, the unsettling dread of the unknown. The best ghost stories do this: the horror of encountering something that, by all logic, shouldn’t be there. The paralysing fear of coming face-to-face with something that surely cannot be real. The MR James style of ghost stories, where supernatural powers are unknowable and unrelenting. Kwaidan, Kobayaski’s collection of Lafcidio Hearn’s Japanese ghost stories, trades brilliantly in this – each of the stories contains moments of real spine-tingling dread that sent goosebumps racing over my body.

Kwaidan is built around four short stories, each separate but thematically linked. In The Black Hair, a samurai (Rentarō Mikuni) leaves his faithful first wife (Michiyo Aratama) for a loveless marriage with the daughter of a rich man. Realising his mistake, he finally returns to her but he stumbles into a haven that becomes a nightmare. In The Woman of the Snow, woodcutter Minokichi (Tatsuya Nakadai) encounters a terrible spirit (Keiko Kishi) in the forest who swears him to secrecy on pain of death – can he keep his silence from Yuki (Kishi again), the woman he marries? In Hoichi the Earless, Hoichi (Katsuo Nakamura) a blind ballad singer, is unwittingly hired by the spirits of a dead warlord. And in In a Cup of Tea, a samurai (Seiji Miyaguchi) is horrified when he sees a reflection that is not his own in a cup of tea.

Simple concepts – and in many cases you can see where this might be going just from the description – but the unnerving sense of dread and the uncontrollable inevitability of the supernatural horrors are what makes this truly terrifying. Kobayashi’s film is slow, careful, precise, and it is this very quality that contributes most effectively to its terror. As the camera moves slowly through unnaturally still and quiet locations, with a soundtrack made of a mix of silence and deeply unsettling, jarring chords and discordant sound from Toru Takemitsu, you actually feel like you want nothing more than to turn and run. Whatever Kobayashi’s camera is slowly edging towards showing us, we know it can’t be anything good. The expectation is a large part of the terror.

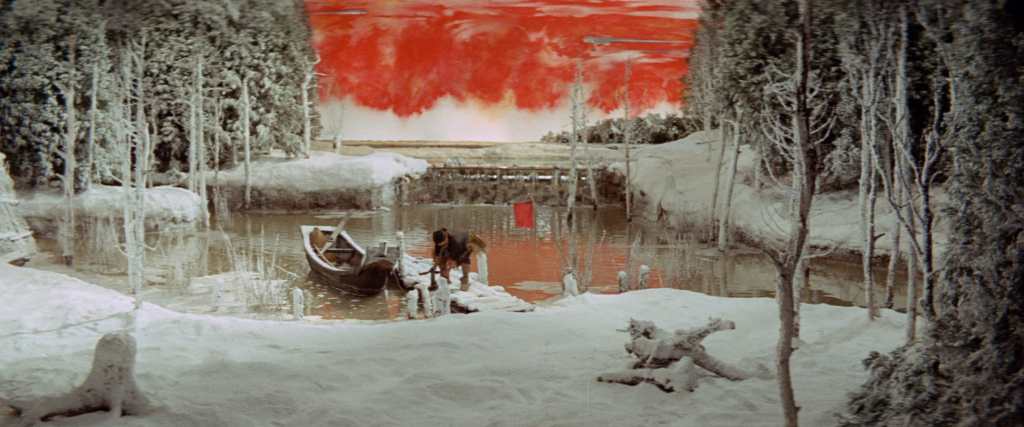

The unsettling world of Kwaidan is magnified by Kobayashi’s desire to control every element of the world he constructed. Bar a few shots of wave-lashed coasts and a Samurai riding competition (presumably too difficult to recreate inside), every scene was filmed inside a massive air-hanger studio. No attempt is made to disguise this. Instead, this exquisitely beautiful film makes a virtue of this to add to the unnerving sense of unreality. Skylines and backdrops are swirling whirlpools of paint and colour, never once trying to suggest a reality. Buildings, fields and even lakes subconsciously feel hemmed in by massive walls of painted unreality. It adds a terrifying fable quality – a nightmareish unreality – to the entire film.

It also makes Kwaidan a uniquely beautiful film. Not since Jack Cardiff’s work with Powell and Pressburger have scenery and backdrops looked as beautiful as this. Kwaidan is an explosion of gorgeous colours, used vividly and imaginatively to suggest mood, themes and threats. In The Woman of the Snow, the spirit seems to suck everything but blues and whites out of the palette – something we notice even more from the orangey skies that surround the woodcutter at every other point. The faded, paler colours in The Black Hair when the samurai returns to his first wife clue us in that all is surely not well. Splashes of red throughout spell danger – a coat, the lining of a pair of sandals, a torn flag, the lining of a cup, all of which the characters ignore.

They ignore these dangers at their peril. One of most dreadful things about the unsettling terrors of Kwaidan is that we can see the outcomes of their mistakes long before the characters do. The stomach-churning dread is waiting for it to happen. It’s executed to perfect effect in The Black Hair. The pompous samurai (a fine performance by Mikuni) is naturally due to be punished for abandoning his wife – and the faded home but unchanged wife he visits after years warn us well before him that horrors will follow. But Mikuni’s horrified shriek when confronted with the truth – and the staggering, nightmare-like, lack of control he seems to have over his body when he realises it (like a dream where you need to run but can’t) – makes this short chapter honestly one of the most unsettling things I’ve ever seen, a true Japanese MR James classic.

Equally fine is the second story The Woman of the Snow. It’s the most lusciously filmed of the four – its painted backdrops are Van Goghian works of art and the colour contrast between the warm summer and terrifying, pale blue winter is extraordinary. Its story is slight, but its spirit – Kishi moving with, again, a nightmarish precision that is deeply unnatural – is terrifyingly relentless. It offers no plot shocks, but the terror of inevitability, to excellent effect.

Kwaidan’s two final stories are less satisfying than these two masterpieces. Hoshi the Earless is very long – almost half the run time alone – and the story most dependent on an understanding of Japanese history. It recreates with a deliberately artificial beauty an ancient Japanese naval battle – clearly taking place in a water tank before a painted backdrop, but dreamlike in its execution, like a half-remembered vision, crammed with striking colours and images. The actual story of Hoshi is the least haunting, but provides Kwaidan’s most lingering cultural image, of a body covered (almost) from head to toe in writing to ward off spirits. Kwaidan concludes with a curiosity In a Cup of Toe a deliberately un-finished story – although the reason it remains unfinished provides Kwaidan with its final burst of shocking horror and another striking, unforgettable image of nightmarish dread.

Images of nightmarish dread abound in a film constructed intricately and deliberately artificially to heighten its sense of horror. The inevitability of many of the outcomes in its story detracts not one jot from the terror – if anything they add to it. Kobayashi’s direction is detailed, controlled, perfectly paced and wrings every last drop of unease from the audience. It’s a film that is long and slow, because the best terror often comes from the lingering slow-build – and its world of disjointed noises and sounds works perfectly to never allow the audience to relax. Kwaidan is an essential and masterful horror film, a collection of the sort of ghost stories that would make you run from the campfire.