I Love Lucy is bought to life in this behind-the-scenes drama that bites off more than it can chew

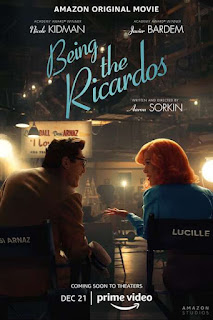

Director: Aaron Sorkin

Cast: Nicole Kidman (Lucille Ball), Javier Bardem (Desi Arnaz), JK Simmons (William Frawley), Nina Arianda (Vivian Vance), Tony Hale (Jess Oppenheimer), Alia Shawkat (Madelyn Pugh), Jake Lacy (Bob Carroll), Clark Gregg (Howard Wenke), John Rubenstein (Older Jess Oppenheimer), Linda Lavin (Older Madelyn Pugh), Ronny Cox (Older Bob Carroll)

A film about I Love Lucy is always going to lack cultural cache outside of the US: it would be the same if a British film about Dad’s Army or Hancock’s Half Hour played there. Without a legacy of growing up on endless re-runs, I think a lot of British audiences (like me) will be left playing catch-up working out who the stars are and what the show is about.

Sorkin’s Being the Ricardos follows one week in the making of I Love Lucy in 1952. It’s a big week. There are rumours of infidelity (from him) in the lives of the married co-stars Lucille Ball (Nicole Kidman) and Desi Arnaz (Javier Bardem). On top of that, the media is running stories that Ball is a card-carrying communist (not completely true). And finally, she’s pregnant, something the network can’t imagine would be acceptable to include in a family show. All these problems come to a head as that week’s show is finalised, rehearsed and shot.

Sorkin’s film is by far and away at its best when dealing with the backstage mechanics behind bringing a TV show to the screen. Which perhaps isn’t a surprise, as that is obviously material he’s very familiar with. The film is fascinating at showing the technical side of things like rehearsals, and it’s very illuminating on the dedicated perfectionism Ball bought to making the comedy work. We see every single gag being worked on over and over to mine the maximum number of laughs from it. There are long back and forth conversations on timing, positioning and nuances of line delivery.

There are similarly fascinating ideas during scenes in the writers’ room. A huge board maps out the details of future episodes. The writers – a neatly squabbling but fundamentally loyal Alia Shawkat and Jake Lacy, headed up by executive producer Tony Hale – are constantly pushed to fine-tune their ideas, while passionately defending many of their own jokes to the sceptical stars.

A sequence essentially showing Ball and the writers spit-balling ideas that will develop into future set-pieces is particularly well done. Sorkin also comes up with a neat visual concept showing how Ball considers the impact of the gags: events from the show play out in black-and-white then switch to colour as the action pauses and Ball considers what to do next to get the most laughs. It’s all part of the film’s primary strength: a fascinating look at the energy and passion required to produce a half-hour sitcom, be it arguing over camera placement to a sleepless and worried Ball calling her co-stars to the studio in the wee small hours to fine-tune a pratfall.

Where the film is less certain is all the other stuff it tries to cover. Being the Ricardos is almost the dictionary definition of a film biting off more than it can chew. It tries to cover: the making of a TV show, McCarthyism, a biography of the marriage of the two stars, the sexism of network TV, racial unease at the Cuban Arnaz playing Ball’s husband, the sexual prudishness of the 1950s, and expectations around gender roles. On top of which, Sorkin’s film trumpets continuously that this was the “most difficult week ever”. It’s an onslaught of stakes the film finds hard to deliver on.

For starters, most of the action focuses on the mechanics of making the show – mechanics that surely would be the same every week. The communist plotline is introduced then largely dropped for most of the film until the final rousing hurrah. McCarthyism is barely tackled, other than a new perspective from Arnaz, who remembers being forcibly driven from Cuba by Communists. Awkward flashbacks fill in some of the backstory around Lucille and Desi’s meeting but end up feeling like superfluous additional information that adds nothing to anything other than the runtime.

Tensions in their marriage bubble away before finally coming to a head, as if Sorkin didn’t want to spoil the rat-a-tat dialogue with some deeper content. The film is very good at showing what a great team they made: Ball’s creativity and comic genius matched with Arnaz’s business-sense and ability to plan every aspect of the show’s technical and financial set-up. But again, more could have been made of this – too often it’s an idea crowded in amongst others, with a tone that can’t decide how it feels about Arnaz’s possible betrayal or Ball’s fixation on it.

More could have been made about the prudish and sexist struggles Ball and Arnaz went through to get her pregnancy integrated in the show. It’s a fascinating realisation that the implication that a happily married couple must have had sex to produce a baby was anathema to TV networks in the 50s. A film that focused on the battle to get this integrated into the show – and the impact that doing so had on America and television – would not only have been more focused, it would also have played into the film’s real strengths: the mechanics of actually making television. As it is, this sense of the struggle Ball had to get due recognition in a male-dominated industry is lost.

As the two stars Nicole Kidman (under layers of latex to transform her facial features into Ball’s) and Bardem are very good, Kidman in particular brilliantly conveying Ball’s comedic genius as well as her self-doubt and insecurity, expressing itself in worries about her marriage to making sure her female co-star looks less attractive than her on the screen. Kidman pounces on Sorkin’s fast-paced dialogue and provides much of the film’s drive and focus. There are also neat supporting turns by JK Simmons and especially Nina Arianda as their co-stars.

In the end though, yet again, it feels like Sorkin the writer is ill-served by Sorkin the director. While the film is more sharply directed than his others, it lacks focus, discipline and drive, like Sorkin can’t bear the idea of cutting some of his own words and ideas so tries to include them all. It ends up meaning nearly all of them lack the impact they should have.