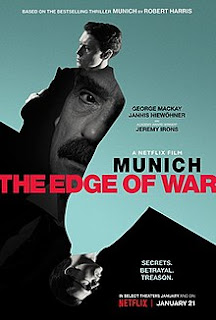

The backstory of history’s most famous empty promise is explored in this solid historical drama

Director: Christian Schwochow

Cast: George MacKay (Hugh Legat), Jannis Niewöhner (Paul von Hartmann), Jeremy Irons (Neville Chamberlain), August Diehl (Franz Sauer), Liv Lisa Fries (Lena), Sandra Hüller (Helen Winter), Alex Jennings (Sir Horace Wilson), Ulrich Mathes (Adolf Hitler), Anjli Mohindra (Joan), Jessica Brown Findley (Pamela Legat), Mark Lewis Jones (Sir Osmond Cleverly)

It’s 1938 and Hitler (Ulrich Matthes) wants the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia. Will the British and French say no? The danger is, if they do, it will lead to a war only Germany is ready for. War is feared by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (Jeremy Irons), who remembers the horrors of the trenches. So, he flies to Munich to make a deal with Hitler. While there, a member of the British legation Hugh Legat (George MacKay) is contacted by an old friend, Paul von Hartmann (Jannis Niewöhner), a German diplomat now extremely disillusioned by the brutal Hitler regime.

Schwochow’s film is a handsomely mounted film version of Robert Harris’ best-selling thriller. Lots of critics called it a “What if” history film, which pretty much suggests people don’t understand what that term means. The film presents a pretty much a faithful (if compressed) version of the Munich talks, rather than some sort of alternative history. What makes it different is the revised angle it takes on Chamberlain – spiced up with a fictional plot about young diplomats trying to bring down Hitler.

Played with an avuncular, praetorian charm by a perfectly-cast Jeremy Irons, Harris book (and this film) presents Chamberlain not as a naïve idiot, duped by Hitler, but a man very much aware of the nature of his opponent, but who felt duty bound to do everything he could to safeguard peace. Chamberlain speaks with real emotion of the loss of a whole generation in the trenches and his fear that Britain is not ready for another war. Sure, Irons’ Chamberlain can also be arrogant and blinkered, convinced of his own cunning shrewdness, but he’s willing to risk his reputation for peace.

What he’s willing to sacrifice of course are the Czechs – and the film doesn’t give a lot of time (if any) to this screwed nation, that saw huge parts of its country split off and handed over to an aggressive power. The film would have been richer with more content around the debates and discussions at the conference and giving more time – as the novel does – to understanding Chamberlain’s strategic thinking. The film implies Chamberlain’s infamous bit of paper was his effort to clarify where blame for eventual war would lie – but it doesn’t allow us to understand more about what Chamberlain initially intended to gain from the conference or when he decided that he was unlikely to win any concessions from Hitler. We never see a moment of the negotiations, which seems a waste for a film that was designed to re-evaluate Chamberlain.

That’s partly because the film, like the book, gives a lot of time to its fictional plot. And like there, never seems to make this seem as vital or interesting as the historical storyline. Perhaps because, while the Munich storyline presents us with something we’ve not seen before, the fictional storyline feels familiar and derivative. George MacKay and Jannis Niewöhner do good work as slightly naïve young men who feel they can change the world, if they find a way to apply pressure at the right moment. But they feel like narrative devices to spice up the history, to throw in a bit of light espionage and peril to stop it being a film about a conference.

But everything feels familiar: clandestine meetings in crowded bars and pubs (surely anyone watching would hear everything?), meetings in parks, document handovers, pacey walks with people looking over their shoulder… It’s all handsomely done but it doesn’t feel fresh. And somehow, since we know (as this isn’t a What if… movie!) that it all end in failure (our heroes spend ages trying to get a copy of the Hossbach memorandum to Chamberlain who basically ignores it immediately) it doesn’t feel urgent enough.

And more interesting personal stories get short-changed. There is more than a hint of sexual chemistry between Hugh and Paul, that the film does more than hint at in performance, but doesn’t explore. Liv Lisa Fries as a young woman both men fall in love with, ends up shifted into a very stereotyped martyr role. There are some interesting ideas touched upon with the growth of a resistance movement to Hitler, but it never quite tells us enough to understand this. And the film shies away from being too bleak in its ending – even though the fates of both our lead characters must surely be a terminal one as they head into the war (given their chosen paths of anti-Nazi resistance cell and the RAF).

I wish the film – just as I felt when reading the book – had dropped most of its standard espionage sub-plot and instead had focused solely on Chamberlain. Especially with an actor as well-suited to the role as Irons. It would have allowed to focus exclusively on re-evaluating and exploring the motivations of those at the conference and the political and military difficulties they faced. Unfortunately, this gets diluted too much, which means we never quite get our perceptions challenged as much as they should. It’s a well-made film, but settles too often for being traditional rather than daring.