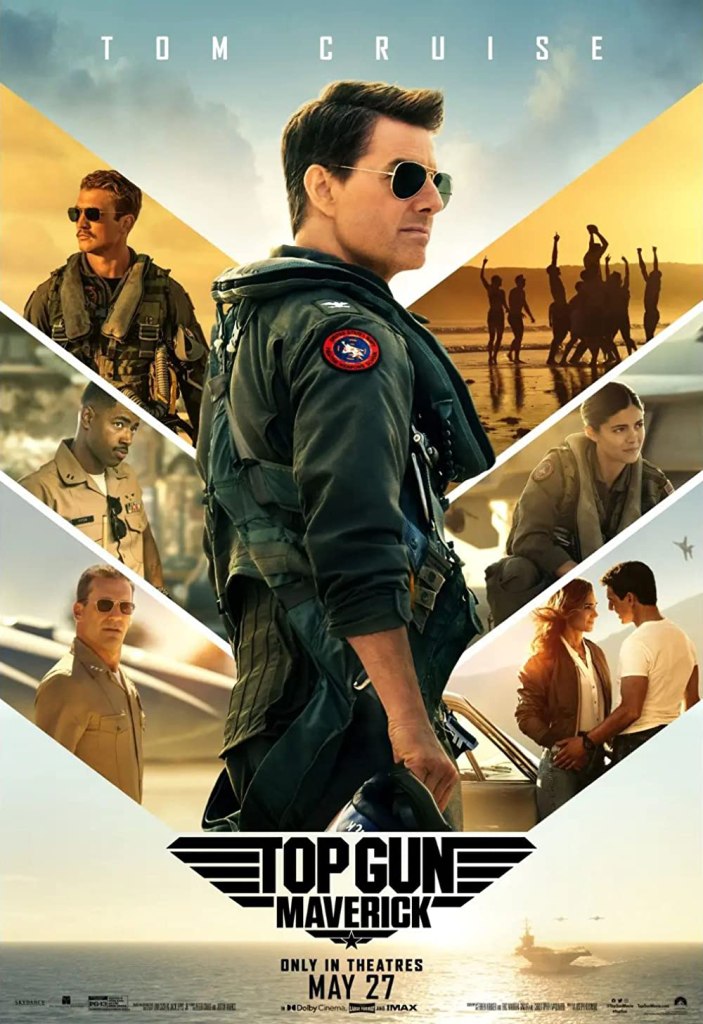

You’ll feel the need for speed in this triumphant better-than-the-original sequel

Director: Joseph Kosinski

Cast: Tom Cruise (Captain Pete “Maverick” Mitchell), Miles Teller (Lt Bradley “Rooster” Bradshaw), Jennifer Connelly (Penny Benjamin), Jon Hamm (Vice Admiral Beau “Cyclone” Simpson), Glen Powell (Lt Jack “Hangman” Seresin), Monica Barbaro (Lt Natasha “Phoenix” Trace), Lewis Pullman (Lt Robert “Bob” Floyd), Ed Harris (Rear Admiral Chester “Hammer” Cain), Val Kilmer (Admiral Tom “Iceman” Kazansky), Charles Parnell (Rear Admiral Solomon “Warlock” Bates)

It’s been 38 years since Tom Cruise last felt that need for speed. Top Gun is a sentimental favourite, partially because its the ultimate brash, loud, Reaganite 1980s Hollywood film. But (whisper it), it’s not actually – and never has been – a very good film. Perhaps though that’s all for the best: Top Gun has so little of merit in it, it offers an almost completely blank canvas for a sequel. It helps the team create Top Gun: Maverick, a film so insanely entertaining it should carry some sort of health warning.

Decades have passed and Pete “Maverick” Mitchell (Tom Cruise) is pretty much the greatest pilot in the world, deliriously skilled at everything in the cockpit and pretty much hopeless at anything outside it. He’s distrusted by all his superiors except his old wingman Iceman (Val Kilmer). Thanks to Iceman he is selected to train the next generation of pilots at TOP GUN for an impossible mission to take out a nuclear plant in a “hostile nation” (clearly Iran). One of that next generation is Bradley “Rooster” Bradshaw (Miles Teller), son of Maverick’s late best friend “Goose”, the guilt for whose death Maverick never recovered from. After Maverick tried to prevent Rooster from following in his father’s footsteps – not able to stand the thought of being responsible for the deaths of both his surrogate brother and son – can the two overcome their problems?

Top Gun: Maverick was delayed from hitting cinema screens for nearly two years thanks to Covid. Cruise resisted all opportunities to sell it to streaming: a decision vindicated by the supreme big-screen entertainment it offers. This one you really do need to see on the big screen. Its aerial footage is so stunning it makes the original look like tricycles on training wheels. Combined with that though, and unlike the original, Maverick has a thoughtful and engaging emotional storyline, with characters who change through well thought out emotional arcs.

But I’ll be honest, the staggering, visceral enjoyment of these plane sequences is probably the principal thing you’ll immediately take out of the film. Working from a training programme partly devised by Cruise, the film shows the impact of punishing G-forces by… actually putting the actors in planes travelling at these huge speeds. Unlike Top Gun, with its blue-screen cockpit shots, there is no doubt Cruise, Teller et al are actually in the planes as they bank at impossible speeds. Partially shot by the actors themselves – sitting the camera up in their cockpits – the film literally shows you the scenery flashing by. It’s Cruise’s mantra of doing it for real taken to a stunning degree. It’s the simple old-fashioned joy of knowing almost everything you see is real.

The mission this time is far more detailed: effectively it’s a steal from Star Wars, our heroes required to fly through a narrow ravine (below the radars of surface to air missiles) before climbing a steep bank and using their laser targeting to successfully blast a small access port. (It won’t surprise you to hear that on the final mission one character has to “use the force” when their targeting laser fails). Maverick’s training programme pushes the pilots to the limit, while his extraordinary flight skills quickly win their awe (in the first session he challenges all the pilots to take him down in a simulated dogfight, with everyone shot down doing 200 press-ups – Maverick does zero, everyone else 200+). Kosinski shoots with a cool clarity that makes you feel you are being punched by G-force.

But Top Gun: Maverick would just be a showcase for cool planes without its emotional heart. And it’s the intelligent and involving story that makes it work. Cruise is at his charismatic movie star best as Maverick – he knows exactly how to win the audience over – but his cocksure confidence is underpinned by a growing sense of fear at the risks he puts others through. Unlike the navy, his main concern is to get the pilots back alive and his guilt-ridden treasured memory of Goose is the hallmark of a man who never managed to put ends before means. He’ll take any risk himself, but balks at taking chances with anyone else’s life.

It’s what drives his troubled relationship with Rooster. The two have a surrogate father-son relationship, fractured by Maverick’s attempt to keep Rooster safe out of the cockpit. (Pleasingly, Rooster does not hold Maverick responsible for his father’s death, only for derailing his career.) The relationship between these two – Cruise’s Maverick quietly desperate to rebuild some sort of familial connection and Rooster shouldering resentment for a father-figure he clearly still loves – is handled with a great deal of tact and honesty. It really works to carry a wallop.

It’s also part of how Maverick’s place in the world, and decisions in life, are being questioned. As made clear in a prologue where he thumbs his nose at a sceptical Admiral (no one scowls like Ed Harris) by taking a prototype jet out for test run, he’s both a relic and a guy who doesn’t know when to stop (he wrecks the jet by pushing past the target of 10 Mach by trying to go another .2 faster). Unlike Iceman – a touching cameo from a very ill Val Kilmer that leaves a lump in the throat – Maverick never fit in within a military organisation (“They’re called orders Maverick”). He’s lonely, his past failed relationship with Jennifer Connelly’s Penny just one of many roads-not-taken. (There is no mention of Kelly McGillis’ character.) In a world of digital drones, he’s an analogue pilot flying by instinct: his days are numbered.

This is proper, meaty, thematic stuff explored in a series of involving personal arcs which by the end not only leaves you gripped because of the aerial drama, but also genuinely concerned about the characters. I can’t say that about the original. Top Gun: Maverick is not only a thematically and emotionally richer story – carried with super-star charisma by Cruise – than the original, it’s also more exciting and more punch-the-air feelgood. This sort of thing really is what the big screen is for.