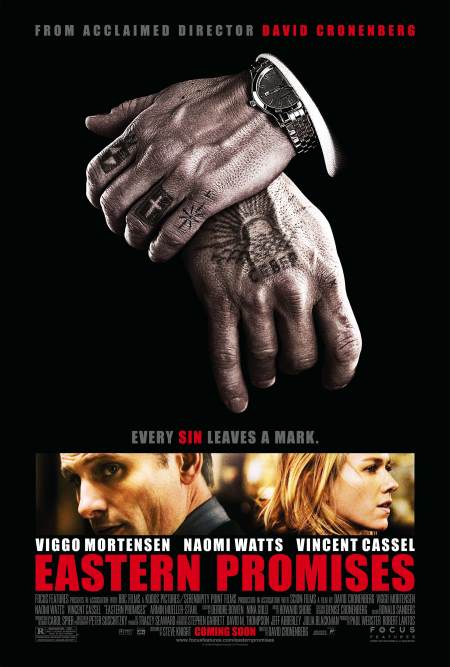

Brutal violence in London’s underbelly in Cronenberg’s formal and chilling dark fairytale

Director: David Cronenberg

Cast: Viggo Mortensen (Nikolai Luzhin), Naomi Watts (Anna Ivanova Khitrova), Armin Mueller-Stahl (Semyon), Vincent Cassel (Kirill Semyonovich), Sinead Cusack (Helen), Mina E Mina (Azim), Jerzy Skolimowski (Stepan Khitrov), Donald Sumpter (Inspector Yuri), Raza Jaffrey (Dr Aziz), Josef Altin (Ekrem), Tatiana Maslany (Tatiana’s voice)

Big promises shipped back to Russian villages, telling women about dreams they can make reality in the bright lights of London. Those are Eastern Promises – but the reality, of sexual slavery and abuse in Russian Mafia controlled houses is horrifyingly different. Set in an underbelly of London just under grand restaurants and red buses, Eastern Promises is a typically tough and bloody gangster fable from David Cronenberg, which plays out like a nightmare fairytale.

It’s the nightmare of midwife Anna Khitrova (Naomi Watts). When a pregnant Russian teenager dies giving birth, the only clue she has to who her daughter’s family might be is a Russian diary and a business card for a Russian restaurant. Anna – whose family are Russian immigrants – is offered help by grandfatherly restaurant owner Semyon (Armin Mueller-Stahl). Seymon is all pleasant insistence that he can help, even as asks after every detail of her life. Because Seymon is a ruthless Mafia kingpin, with a hapless son Kirill (Vincent Cassel) leaning on the emotional and practical support of his imposing, heavily tattooed driver Nikolai (Viggo Mortensen). As Anna is pulled further and further into Semyon’s deadly world of death, could she have a surprising saviour?

Cronenberg’s film, sharply scripted by Steven Knight, is shot with a traditional stillness and a palette of strong colours – all of which reassuring visual language is utterly at odds with the skin-slashing violence at its heart. Eastern Promises opens with a Russian gangster practically having his head sawn off with a switchblade, in the hands of a mentally-handicapped nephew of a minor Turkish gangster. There isn’t a single gun in Eastern Promises – after all that would be breaking British law! – instead violence is meted out with the violent intimacy of a knife across the throat.

The film’s formal structure and framing – angles and cutting are kept simple, almost static – works brilliantly. As we watch throats slashed, grim sexual encounters or moments of imposing menace, the matter-of-fact presentation of these become more-and-more chilling. Eastern Promises feels like a bogey-man fable. Seymon’s restaurant – all class and bright red walls – an ogre’s cavern that leads us into an ever-grimmer world of violence and mayhem.

It’s a world Anna is unprepared for. Determined and resilient, Naomi Watts’ Anna is also undone by her politeness. How can she refuse an offer to help from someone as polite as Seymon? Watts does extremely well with a slightly under-written role, a woman on a quest who slowly realises how terrible the world she is peeking into is, but stop from trying to force through what she believes is right. Her disbelief – and out-of-place semi-innocence and sense of moral duty – make her stand out all the more in this terrible underbelly world, full of ogres and secret codes.

At the centre of is a monster. Armin Mueller-Stahl looks like your favourite uncle, but he quietly exudes cold, remorseless villainy. He’s the sort of man who delights in cooking the finest borsch, playfully teases his granddaughter’s violin playing and doesn’t bat an eyelid about ordering a rival to be dismembered. Mueller-Stahl is terrifying as this man the audience instinctively knows is dangerous and will stop at no moral boundaries to get what he wants (watch the steely eyed kindness he asks Anna where she works, lives and who she knows during their first meeting).

The obvious moral void in Seymon makes the unreadable Nikolai even more intriguing. Played with an extraordinary physical and linguistic commitment by Mortensen, Nikolai’s body is a tattooed walking advert of his past and capacity for violence and he’s the sort of relaxed heavy who is as unfussed with stubbing a cigarette out on his tongue as he is with snipping fingers off a corpse. Mortensen’s skill here is to make us constantly unsure where the moral lines are for Nikolai. He is a confirmed killer, but he takes an interest in Anna. Is this sexual or protective? What does he make of his bosses’ brutality towards women? What does he think of his direct superior Kirill?

Kirill is played with a larger-than-life weakness by Vincent Cassel in a thrilling performance that constantly shifts expectations. At first, he seems like a drunken blow-hard with a capacity for thoughtless violence. But Cassel makes clear he is a weak man with some principles, bullied by his father (to whom he is a constant disappointment), desperate to prove he is more capable than he is. He has an emotional reliance on Nikolai laced with sexual fascination (he can barely keep his hands off him).

Nikolai seems to accept this. But we don’t seem to know why. His actions are constantly open to interpretation. Ordered to have sex with a prostitute, he almost apologises to her after – left alone with her after Kirill has watched their sexual encounter, he’s strangely tender. He urges Anna to keep her distance but follows orders with calm disinterest. How far will he go? What moral qualms does he have, if any? Mortensen’s carefully judged performance is a master-class in inscrutability in a film that plays its cards very close to its chest as to why he (and others) do the things they do.

Cronenberg’s entire film is structured like this. Is the dragon a dragon or a potential knight? Can Anna emerge from this semi-Lynchian nightmare world and return to normal life – or will everything connected to her be destroyed by this world. Cronenberg’s study of this shady, heartless world is masterful. The “rules” and code of this brutal Russian Mafia world are excellently explored. And the film’s formal style culminates in a stunningly violent but beautiful (if that’s the right word) fight between a nude Mortensen and two knife-wielding Checians in a Turkish bath that is a brutal model for how these things can be done.

Eastern Promises resolves itself, after twists and turns, into something more comforting and traditional than you might expect. But is it a fairy tale ending to a nightmare? Either way, Cronenberg’s mix of formality and unflinching gore is masterful and in Mortensen it has a performance both relaxed and full of tightly-wound violence. Tough but essential.