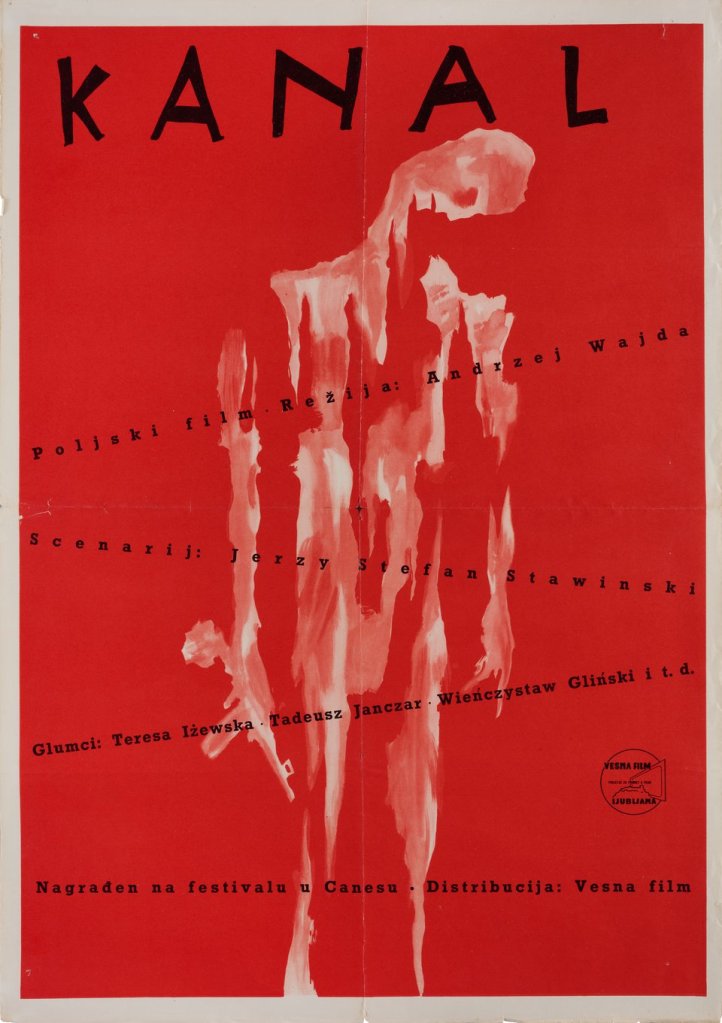

Wajda’s war-epic is a brilliantly filmed, unsettling critique of the truth behind national myths

Director: Andrzej Wajda

Cast: Teresa Iżewska (Daisy), Tadeusz Janczar (Jacek “Korab”), Wieńczysław Gliński (Lt. Zadra), Tadeusz Gwiazdowski (Sgt. Kula), Stanisław Mikulski (Smukły), Emil Karewicz (Lt. Mądry), Maciej Maciejewski (Gustaw), Vladek Sheybal (Michał, the composer), Teresa Berezowska (Halinka)

By 1957, Wajda was working under a very different Polish government from the one in place for his debut feature A Generation. With the fall of Stalinism came an easing on restrictions and controls. Wajda could address themes he couldn’t touch before, helping make Kanał perhaps even more controversial than A Generation, as it explored Polish sacrifices during the Second World War and, by implication, asked what the point might have been. Focusing on the final days of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising – a revolt against the German occupiers which the Soviets effectively stood by and watched the Wehrmacht crush – Kanał gives a Polish National myth a tragic human face of futile effort.

Not quite what Wajda’s bosses in the Polish Film Industry expected. Perhaps the title should have tipped them off: Kanał translates as Sewer, hardly suggesting a heroic tribute to national sacrifice. Starting on the 54th day of the Warsaw Uprising, the Home Army forces are beaten, clinging to a few streets. Introducing a unit commanded by Lt Zadra (Wieńczysław Gliński) in a long tracking shot through a devastated city, an unseen narrator bluntly tells us in the opening moments everyone we see is about to die. But not in a last charge against the Germans: instead it will be in the sewers, while attempting to escape, waist deep in shit, lost in the dark and stumbling into dead ends, madness, exhaustion and booby traps.

For many Poles this didn’t fit with the idea of the Warsaw Uprising being a heroic, necessary battle for the nation. It’s rather like in the 1950s, a British film studio had made a film about the Battle of Britain in which the pilots got tanked up on booze then took to the skies to be pointlessly shot down by the Luftwaffe over the channel. At least Wajda this time could present the Home Army – who, following the government line, A Generation had condemned as bourgeoise, fusspot cowards – as heroes. And Kanał is mercifully free of blunt political messaging: no one has time for any of that when they are simply desperate to survive.

What it’s also free of though is any tangible achievements from the Polish Resistance forces. Zadra’s unit holds onto a trashed district, under heavy fire, taking more and more casualties for about a day before being ordered to withdraw through a city pounded by shells through desperate civilians. During the entire course of Kanał the Poles inflict three casualties on the Germans: one tank is hit (but not destroyed), one unmanned motorised mine is stopped and one German soldier who falls into a defensive trench is beaten to death with a stone. Other than that, this is a one-sided curb-stomp where the Germans are hardly even seen and the Poles take huge casualties without even the most basic, morale boosting minor victory.

Kanał’s first half, which covers the war up-top is gritty, immediate and a truly scintillating piece of brutal combat. Wajda’s cinematic confidence is clear from the start with that long Wellesian tracking shot introducing all the characters as they move from one ruined district to another. His combat scenes take place on a wasteland of smashed buildings and have a panicked pointlessness to them – confused and desperate soldiers responding rather than planning anything proactive. The one undeniably heroic act we see – Jacek’s (Tadeusz Janczar, once again Wajda’s complex sacrificial lamb) taking down of the motorized mine – sees him near-fatally wounded, reducing him to a limping, slowly dying passenger for the rest of the film.

The atmosphere behind the lines is already tipping into desperation: number two soldier Mądry (a swaggering Emil Karewicz) is bedding young fighter Halinka (a fragile Teresa Berezowska) openly, while composer Michal (Vladek Sheybal, excellent as a haunted outsider) attempts to call through to his wife and children on the other side of the city, only to listen in on their deaths over a phone line. Any sense of chain of command is crumbling, and the soldiers are already hardened to death and destruction: retreating through the city, none of them can muster even a flicker of interest in a desperate mother begging for news of her lost child.

That’s nothing though compared to the bleakness of the film’s second half as the unit piles into the sewer. Here, time and space start to lose all meaning. The film’s timeline becomes as unclear for us as it does for the characters as they trudge through this Dantean sludge (Wajda makes sure we don’t miss the point, in a slightly clumsy touch, by having Michal quote the poet at length). With limited light, no real idea where they are going, low motivation and toxic gases being stirred up from the excrement they are crushing under their feet, slowly sanity slips, people revert to their worst instincts and selfish, unheroic decisions are made.

There is little to build a national myth on here. An incoherent colonel is left to die in the mire. Mądry and record keeper Sgt. Kula (a comradely Tadeusz Gwiazdowski) decide their own lives are more important than those of the company. Zadra clings to his duty, but lost and confused utterly fails to maintain any duty of care to his men. Michal, teetering already with the loss of his family, disappears into his own world. Their guide Daisy (a brilliantly humane Teresa Iżewska) abandons her duty in what we already know is going to be a futile attempt to keep Jacek alive. There is no dignity or final heroic act of death, with people meeting the end with stunned silence, clumsy tiredness or panic.

And over it all is the statement Wajda implies: since the Uprising achieved nothing but the massacre of its fighters, to a Wehrmacht driven out months later with ease by the Soviet forces, what was the point? That, however much the Communist state chose to praise the bravery of the soldiers, was it brave or foolhardy to single themselves out as targets in a one-sided battle that achieved nothing? Watching the fighters of the Uprising wade through excrement towards a lonely, uncelebrated death with nothing to show for it, makes you consider the complex feelings that lie behind National myths of sacrifice. And it’s a powerful and haunting message for this mesmerising sophomore effort.