Wajda’s masterpiece of subtle but stinging Soviet criticism and one of the great European films

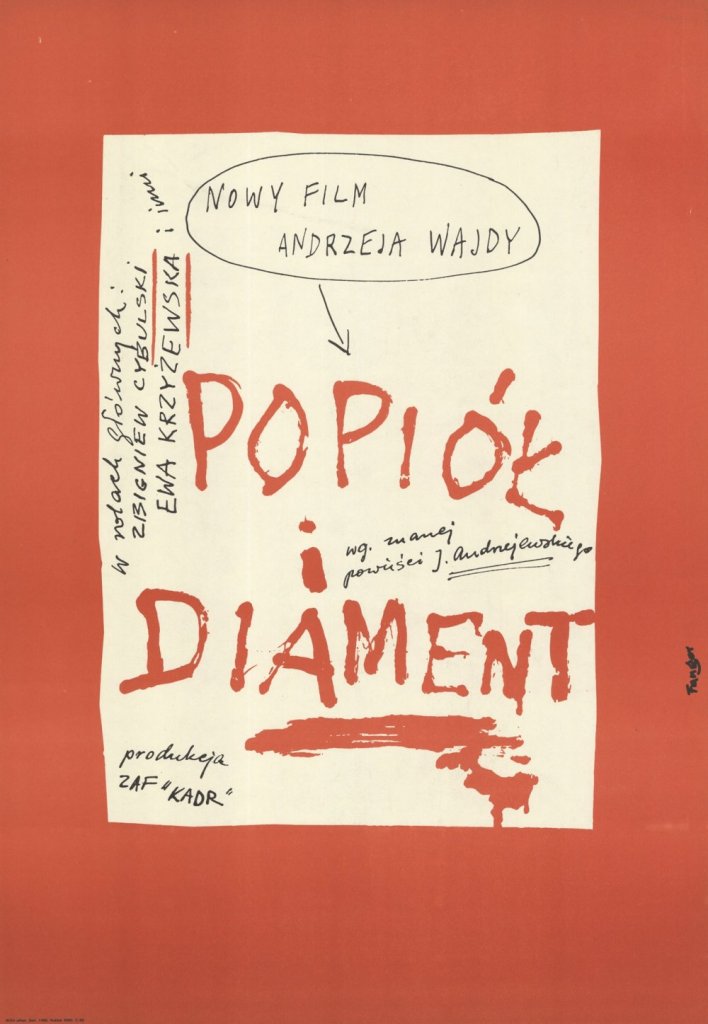

Director: Andrjez Wajda

Cast: Zbigniew Cybulski (Maciek Chełmicki), Ewa Krzyżewska (Krystyna), Wacław Zastrzeżyński (Szczuka), Adam Pawlikowski (Andrzej), Bogumił Kobiela (Drewnowski), Stanisław Milski (Pieniążek). Ignacy Machowski (Waga)

When the dust settles from the chaos of uncertain, terrible times what will we it leave behind: ashes or a diamond? It’s a question Poland is asking on the final day of the war, 8th May 1945 –what fate will come under Soviet rule? Wajda’s War Trilogy comes to its end and, even considering the quality of the first two films in the series, Ashes and Diamonds is a quantum leap in filmmaking, an extraordinary mix of realism and poetic ambiguity. Wajda captures this turning point in Polish history with a series of encounters between a group of characters in a single location on one night. Ashes and Diamonds can lay claim to being one of the greatest films from Eastern Europe in the twentieth century, a breathtakingly rewarding mix of subtle messaging and tragedy.

Home Army fighters – those paying attention to Wajda’s earlier work will be well aware the Polish government strongly disapproved of these forces loyal to a democratic Polish government – Maciek (Zbigniew Cybulski) and Andrzej (Adam Pawlikowski) attempt to assassinate communist leader Szczuka (Wacław Zastrzeżyński). Instead, they accidentally murder two regular workers. They are ordered to take a second attempt on their target after he attends a celebration with a host of Polish and Soviet dignitaries at a local hotel. But triggerman Maciek is torn, trapped in a cycle of war that has killed his friends, uncertain about whether to continue in the crusade that has consumed his youth or explore a life he glances at with barmaid Krystna (Ewa Krzyżewska). Will Maciek complete his mission or accept Poland’s future lies not with the ‘liberating’ Soviets?

Wajda’s restructuring of Jerzy Andrzejewski’s novel is the culmination of the entire War Trilogy’s style: a careful criticism of Stalinism, buried behind ambiguous characters and images that provide enough of an interpretative fig-leaf that the Polish authorities could convince themselves his work was politically acceptable. Nearly everything in Ashes and Diamonds is subtly open to interpretation, carefully hiding its message in plain sight: the war is bringing ashes to Poland, not diamonds. Certainly, today, that’s the only interpretation you could take from Wajda’s extraordinary ending: our assassin writhing in painful, fearful death-throws on a rubbish heap while the hotel guests dance slowly and hypnotically into a doorway bathed in light. The beautiful ambiguity though is clear: look, Wajda could say to his political masters, they’re heading into the light while the Home Army soldier literally dies in a pile of rubbish. How more pro-Soviet can you get?

The entire film is a sad poem to a lost Poland with Wajda carefully guiding our sympathy towards Maciek. On paper, there’s plenty to admire in Szczuka, clearly an honest, competent politician – but he’s also uncharismatic and dull, who we may respect but never love. All our sympathies are captured by Zbigniew Cybulski’s extraordinary performance as Maciek. Inspired by James Dean and Marlon Brando (having binged their films while studying in Paris), Cybulski effectively wears his own clothes and gives Maciek the sort of anti-authority cool Dean made his own. Our sympathies lie immediately with this young man turned reluctant warrior, angry and scared.

Cybulski’s performance isn’t just attitude. He makes clear Maciek is deeply traumatised by the things he’s seen and done. Those dark glasses he wears – which make him look both older, cooler and more cocksure (he looks noticeably younger and more vulnerable without them) – are a legacy of damage to his eyesight from the sewers of the Warsaw Uprising. There’s an odd childish vulnerability to him – he’s spooked by ants crawling across his machine gun during their opening botched assassination – along with a surly resentment at the never-ending demands of this war. But he’s also iconoclastic and passionate about the vision he’s been fighting for. All of this is beautifully captured by Cybulski.

Maciek is at the centre of this pained reflection on all that has been lost in the war. Wajda presents this lingering sense with a series of strikingly unforgettable images. Maciek and Andrzej toast their fallen comrades with burning shots of vodka, each lit like a candle as they remember another name. Flames mark death and loss throughout: the innocent man accidentally machine-gunned by Maciek falls with his jacket burning from point-blank gunfire, fireworks fill the sky when Maciek carries out his assassination.

And where is the Church in all this? Ashes and Diamonds come back time and again to the great spiritual guide in Polish lives (before Socialism). The early assassination takes place outside a countryside Church, its locked door failing to save the victims. It’s an ominous sign for a world where God may have fallen silent, or perhaps never spoke at all. In another brilliant touch of Wajda ambiguity, Maciek and Krystyna walk through a bombed-out church, encountering a giant crucifix hanging upside down. This is not only an extraordinary image – the thorns from Jesus’ head either seeming to visually skewer the lovers or pull them in – but also a confirmation or lament for how little God can help Poland. Maciek clearly doesn’t care, since he happily uses altar decorations to fix Krystyna’s shoe. Faith doesn’t matter in this world.

All people have to belief in is what they can muster in themselves. Perhaps that’s why Maciek has filled his life with the longing to keep the good old cause going. He’s lost so much, he can’t actually believe there is anything else he could really do. For all his flirting at the bar, brimming with cocksure cool, does he ever really believe he has any choice but to continue with what he has committed to do? Wajda frames Maciek in his final moments of choice, huddling under stairs, shadows seeming to box and cage him in.

He’s as trapped as the rest of Poland is. Szczuka is a decent man, but he’s also a Socialist fanatic horrified to hear his son fought for the ‘reactionary’ Home Army. Meanwhile, his Soviet paymasters carefully nuzzle themselves into control over the Polish authorities, Wajda presenting them always with a careful political neutrality. Cunningly, all criticism of them is placed in the mouth of a journalist who speaks nothing but the truth about the freedom-crushing Soviets – but he’s made a drunkard sleazeball (more than enough for the censors to dismiss his words).

Ashes and Diamonds is also a beautiful piece of filmmaking, crammed with Wellesian light and shadow. Despite mostly being a film about waiting and decision making, it’s also full of pace, energy and a sense of a world steamrolled out of existence. It has one of the legendary endings, not only the long, lonely death of our hero but also the hypnotic, slow dance of the Polish authorities, disappearing into the sunlight, unknowingly marching into a future that will extinguish them.

Wajda manages to communicate all this in a film which, thanks to its need to slip everything past the censors, is extraordinarily supple and subtle, never over-playing its hand and spreading its humanity. There are no real villains here, only a series of people at a turning point of history, presented with careful even-handedness, but in way that never intrudes on the obvious sympathies of the film. With extraordinary direction and a superb, era-defining performance from Cybulski, it’s a masterpiece of World Cinema.