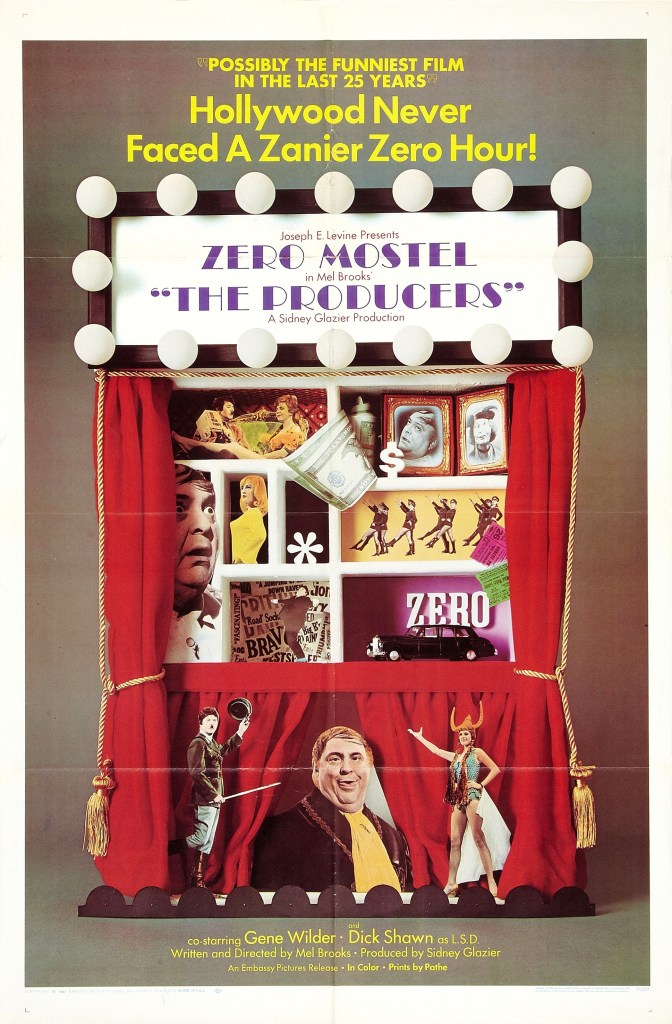

A funny gag sits at the heart of a film that’s more cheeky than really funny or clever

Director: Mel Brooks

Cast: Zero Mostel (Max Bialystock), Gene Wilder (Leo Bloom), Dick Shawn (Lorenzo St. DuBois (L.S.D.), Estelle Winwood (“Hold Me! Touch Me!”), Christopher Hewett (Roger De Bris), Kenneth Mars (Franz Liebkind), Lee Meredith (Ulla), Renée Taylor (Eva Braun), Andreas Voutsinas (Carmen Ghia)

“Don’t be silly, be a smartie/Come and join the Nazi Party!” The cheek of a knockabout musical Hitler musical is the sort of stroke of genius only Mel Brooks might have come up with (and got away with). It’s the saving grace of The Producers, an otherwise rather pleased with itself, slight film whose cheeky gags look like they are taking a pop at sacred shibboleths but actually conform rather neatly with common (at the time) perceptions of women, homosexuals and randy old people. So much so, the film looks more braver and cheekier today when its relatively innocent sexism and homophobia comes across as cheeky tasteless fun rather than pretty much being par-for-the-course.

Max Bialystock (Zero Mostel) is the least successful producer on Broadway. But perhaps he can turn that to his advantage when neurotic accountant Leo Bloom (Gene Wilder) points out that overselling shares of a guaranteed flop can make way more money than a hit. They just need a play that will definitely bomb: what better choice than Springtime For Hitler, a ludicrous musical tribute to Hitler written by dim Nazi Franz Liebkind (Kenneth Mars). Just to make sure they get the bomb they need, the duo hire talentless camp director Roger de Bris (Christopher Hewett) and stoned hippie lead (Dick Shawn). What could possibly go wrong? Or, rather, right?

There is a wild comic zaniness to The Producers epitomised by Zero Mostel’s manic energy as Max, a sleazy, sweaty mass of greed and self-obsessed vanity, totally devoid of any sense of shame. The Producers gets away with a lot because, like Max, its utterly shameless and frankly doesn’t give a damn what you think. Whether you find it hilarious or not depends on how much you are taken by provocative humour and scattergun cheekiness. There is an end-of-the-pier quality at the heart of The Producers (in the UK it would have been Carry On Up Broadway). Brooks doesn’t miss an opportunity for smutty postcard humour. It’s all so naughty he gets away with the ridiculousness of a Hitler musical.

A Hitler musical that wisely satirises the Nazi’s Riefenstahl showmanship via ludicrous Broadway choreography (including tap dancing stormtroopers forming themselves into dancing swastikas). Of course, Brooks is clever enough to keep the actual content of the musical purely on a surface level (no talk about what the Nazis actually did beyond aggressive militarism) – combined with Hitler portrayed as a bumbling Hippie full of the streetwise slang of pony-tailed sixties counter-culture. At heart, Springtime For Hitler doesn’t really do anything really more shocking or provocative than put blackshirts into 42nd Street. It also carefully distances itself from the antisemitic elephant-in-the-room by having Bialystock and Bloom rip off the swastika armbands they agreed to wear while wooing Liebkind, throwing them in a bin and spitting on them. It’s a neat balance that allows the film to get away with as much as it does, while never touching the nightmareish darkness of the regime.

Of course, it helps that Brooks is one of Hollywood’s most famous Jews – and that Mostel and Wilder delight in leaning into a very Jewish comedy about a couple of shmucks enjoying being rogues. Wilder in particular is fantastic. While Mostel is at times be a bit much, Wilder’s hilarious snivelling childish timidity (he’s obsessed with a comfort blanket, the loss of which turns him into a mass of bleating despair) ‘blooms’ into the delight of an eternal good-boy finally allowed to be naughty. Wilder gets the balance just right between something larger-than-life and something real and when he talks about Bialystock being his first and only friend, it’s strangely moving.

Wilder, alongside the scenes taken from Springtime For Hitler, provides most of the humour. I’ll be brutally honest – I’ve never found much of the rest of The Producers funny. Nearly every other joke in the film relies on smut and cheek. Bialystock makes what money he does from pimping himself to randy octogenarians (never men obviously, that would be too risqué), and The Producers buys heavily into the idea that the sex lives of anyone over the age 60 is hilarious. It’s a cheap and rather repetitive joke, made over-and-over that Zero Mostel just about manages to sell because he embraces Bialystock’s utter lack of restraint. But it’s a one-note joke that outstays its welcome.

The Producers similarly makes rather obvious, one-note, jokes about all its female and gay characters. (Again, at the time much of this would not have been out-of-the-ordinary, so it actually looks more bizarrely more boundary pushing today). Ulla, Bialystock’s Swedish secretary, is a blonde sex-bomb whose recurring joke is her oblivious sexiness and willingness to burst into erotic dancing at the drop of a hat. She’s explicitly hired by Bialystock as a glamourous piece of eye candy ‘toy’ as a reward for his self-pimping and it’s not particularly funny. Also not particularly funny is the play’s director, a cross-dressing, mincing figure of camp satire played by Christopher Hewett, the main joke being he is a ridiculously overblown queer who wears a dress. Kenneth Mars’ Franz Liebkind – a ridiculous relic of the Reich, incompetent at pretty much everything he attempts – is slightly more amusing, if only because he’s utterly oblivious to his complete uselessness.

Brooks’ film is, you suddenly realise, rather slight. At around 80 minutes, it’s heavily reliant on its show-stopping glimpses of the Nazi musical (and even in that Dick Shawn’s Hipster swagger isn’t as funny as the Broadway parody) and aside from that relies on predictable farce, cheek and smut. Only Gene Wilder really transcends the material with a perfectly timed, strangely touching performance. Other than that, it feels like a film trying very, very hard to be a little bit-naughty, like an over-extended student revue sketch. But “Don’t be silly be a smartie/Come and join the Nazi party”? That is funny.