Lush romantic adaptation settles for tourism and pretty pictures instead of any emotional or narrative weight

Director: Rob Marshall

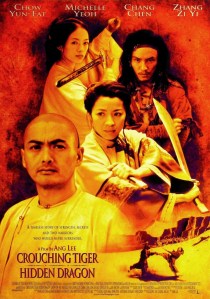

Cast: Zhang Ziyi (Sayuri Nitta/Chiyo), Ken Watanabe (Chairman Ken Iwamura), Michelle Yeoh (Mameha), Gong Li (Hatsumomo), Suzuka Ohgo (Young Chiyo), Kōji Yakusho (Nobu), Kaori Momoi (Kayoko Nitta), Youki Kudoh (Pumpkin), Kotoko Kawamura (Grandmother Nitta), Tsai Chin (Auntie), Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa (the Baron), Samantha Futerman (Satsu Sakamoto), Mako (Mr. Sakamoto)

In 1920s Japan, 9 year old disgraced former geisha pupil Chiyo (Suzuka Ohgo) meets a businessman, Chairman Ken Iwamura (Ken Watanabe), who is kind to her. She resolves to one day become a geisha so she may see him again. As a young woman, Sayuri (Zhang Ziyi), as she is now known, masters the geisha arts under the tutelage of famous geisha Mameha (Michelle Yeoh). She encounters the Chairman again – but can she confess her love? And can she escape the attempts of her rival Hatsumomo (Gong Li) to destroy her?

Arthur Golden’s romantic novel was a major success in 1997, tapping into a fascination with Japanese culture. It was inevitable it would come to the screen. But in the journey, it has been stripped down into a beautiful but basically empty story, that seems trite and shallow and revolves around hard-to-invest in characters. By the time it’s finished you’ll wonder what the fuss was about.

The reconstruction of 1920s-40s Japan does look radiant, even if the film focuses on the most chocolate-box, touristy view of Japan you could possibly imagine (think of a Japanese item, event or object and it’s in the film). But it’s radiantly shot and intricately put together – the geisha costumes are a gorgeous, multi-layered, decorative treat – and it’s not a surprise the film lifted three Oscars for cinematography, production and costume design.

It’s not a surprise as well that it was overlooked in all the majors. It’s well-directed by Rob Marshall (juggling a multi-lingual cast and framing the film beautifully), but fundamentally a mix of the highly predictable and the deeply troubling. It’s basically Geisha Expectations or Jane Geishyre. Our heroine is a poverty-stricken youth who makes a series of key encounters in her childhood that shape her whole personality as she comes into wealth as a young adult. Similarly, this quiet girl’s obsessive love for a distant businessman (whom, yuck, she meets as a child – and he compares her to his own children), suffering quietly while sacrificing everything to help him.

But it’s all much less interesting than either of those novels. Despite the narration by an older Sayuri, we never get inside the young woman’s head. Ziyi Zhang is given very little to work with: she either looks distressed, simpering or sad, and frequently fades into the background of her own story. All we really learn about her is that the Chairman gave her an ice cream when she was 9, and that this event influenced her entire life. Equally dull is the Chairman himself, whom Watanabe struggles to make anything other a mute and inscrutable character, terminally dull.

It’s hard to invest in a love-across-the-ages (in every sense) romance between these two, because the film fails to build them up as characters we care about and gives them hardly any time to be together. By the time we reach a late confession, that the Chairman decided (when Sayuri was 9) to turn her into his ideal geisha (um, grooming anyone? Oh yuck) and they finally kiss each other, they still feel like complete strangers. She never matures into a woman who can fall in love past her childhood obsession and he seems more like an oddly manipulative sugar daddy.

Memoirs of a Geisha flounders on the empty plot and non-characters at its heart. It ends up relying on the visuals and lovely design work, because there is no drive or interest in its plot. The film’s most compelling performance is Gong Li’s Hatsumomo and when she walks out of the picture three quarters of the way through, it never recovers. Gong is superb as an envious, embittered geisha being replaced by younger faces. She snipes and growls like a relic from a Bette Davis Hag-thriller, but in the next scene her face will crumple with fear and sadness. She gets all the best lines and the most interesting scenes, from sniping, to lost love to pyromaniac revenge.

Memoirs of a Geisha disappointed at the box office. It’s clumsy casting didn’t help: fine actresses as Zhang, Yeoh and Gong are, they were all Chinese (in Yeoh’s case Malaysian Chinese) rather than Japanese, and there was an uncomfortable feeling that the producers didn’t think this was really an issue. It opened up a can of worms about lingering Chinese hostility over Japanese war crimes, leading to a ban in China. In Japan, the casting was condemned and the film seen as more interested in a tourist eye on geisha culture than a truly Japanese one (and it does appear the film consulted virtually no Japanese people during its making).

All the glorious design in the world can’t hide the emptiness at the heart of Memoirs of a Geisha. World War Two is skipped over in about two minutes (Sayuri spends the time working in the hills, and sums up her whole wartime experience in a couple of sentences, delivered in voice-over while Zhang looks beautiful and pained washing fabric in a river). Other than their external glamour, we don’t learn much about what being a geisha actually means. Its central romance goes from bland, to anonymous, to deeply troubling. It looks wonderful, but if there was anything deeper to the novel than a luscious, gorgeous setting and a predictable, traditional romance, it’s completely lost in translation.