Skolimowski’s passionate call for animal rights is a modern Au Hasard Balthasar

Director: Jerzy Skolimowski

Cast: Sandra Drzymalska (Kasandra), Tomasz Organek (Ziom), Lorenzo Zurzolo (Vito), Mateusz Kościukiewicz (Mateo), Isabelle Huppert (Countess)

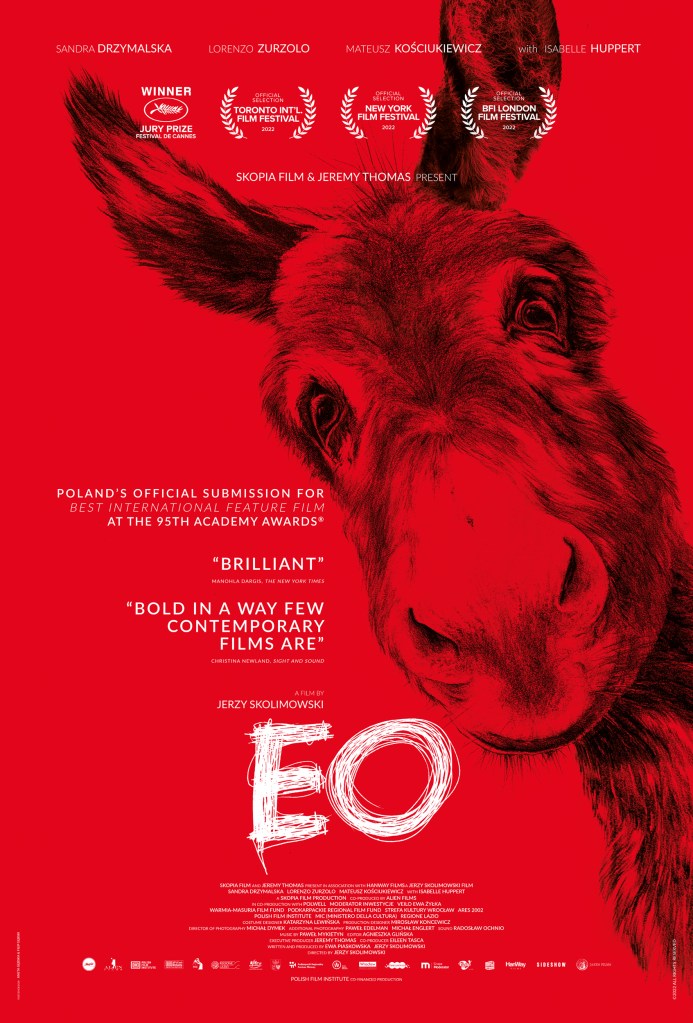

You can make a lot of judgements on humanity, based on how it treats animals. EO, a poetic and deeply heartfelt film, makes a passionate plea for kindness and respect in our treatment of the natural world, qualities it all too often finds lacking. In that sense, it’s surprisingly different from its ancestor Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthasar. Where Bresson turned the rite-of-passage of a donkey into a Calvary-like journey, with the donkey a poetic substitute for Christ, Skolimowski’s film presents a donkey who is nothing more or less than a donkey, but whose experiences become universal for our treatment (and mistreatment) of animals.

We first meet EO as a circus performer, working closely performing tricks with Kasandra (Sandra Drzymalska). When the circus’ finances collapse, under the demands of animal rights activities EO is taken from his home and deposited in a sanctuary where he feels unsettled and uncertain. From there, his life becomes migratory as wanders encountering violent football hooligans, exploitative mink farmers and the odd decent person, progressing towards an abrupt fate that parallels Bresson’s Balthasar.

Even more so than Bresson’s work, Skolimowski’s EO front-and-centres its donkey star. Among many things, EO is a strikingly beautiful art film. The camerawork – shot by two DPs who pull the film together into a beautifully consistent visual style – is radiant, presenting a series of luscious 4:3 images which capture both the beauty of nature and the starkness of man’s presence in it. Several scenes are shot with a slightly frog-eyed lens, its blurred wet-looking edges suggesting EO-perspective POV shots. Skolimowski presents several sequences with a red-tinged dream-like quality, that suggests EO’s own day-dreams – soaring vistas, locations that visually merge together, flashes of his circus life. All this pushes EO himself into the film’s lead role, a real character.

But yet no attempt is made to anthropomorphise this animal. Although the camera lingers over EO’s face, his emotions are left entirely for us to interpret. In many ways, EO is a proof for that old editing test: show the same neutral face followed by a series of contrasting happy and sad events, and the mind will interpret that neutral face as holding different emotions. That is what EO does marvellously. Perhaps we just imagine EO’s joy at seeing Kasandra again (she is certainly moved – drunk, but moved). Perhaps his fear and discomfort in his new animal shelter home is us reading in what we might feel in his place. When EO kicks a mink battery farmer in the face, do we feel he’s angry because we are? There are no answers from EO: he’s just a donkey.

Nevertheless, he is a donkey on a journey and Skolimowski’s film is a surprisingly sharp-edged fable, deeply critical about our unthinking, brutal exploitation of animals. To too many of us, the film argues, their rights are not worth considering – they are dumb creatures good to work until they are too difficult to keep alive or we wish to use their bodies for something else, from clothing to food. EO’s encounters with humans invariably see him being used for their own needs, rarely considering what the desires of the donkey might be.

Skolimowski establishes from the film’s opening, with its animal rights activists who are (surprisingly considering the film itself is an act of animal rights activism) smug, self-righteous and so convinced they know what is best for EO that they are crucial in separating him from the only human in the film who cares for him. Far from ill-treated in the circus, it gives EO a home, love and a purpose. The instant he is removed from this circus, all three of these elements disappear from his life.

Not that Kasandra is an unequivocally positive influence in EO’s life. Settled onto a farm – again we read depression into his refusal to eat, although maybe EO’s just not hungry – EO’s new surroundings are not unpleasant (in fact, the farm seems to be partly about helping disabled children connect with animals, in a sweetly touching sequence). Kasandra gate-crashes one night, drunk, feeds EO a muffin and then disappears over the horizon. Her presence does enough to cause EO to follow her, escaping from his pen and walking out into the Polish countryside.

This pilgrimage through a forest and shooting range (laser guided hunters track wolves, EO at one point starring at a dying wolf, left to bleed out from the hunt), leads eventually to a village football game where EO’s braying causes one side to miss a crucial penalty. Suddenly EO is flotsam in a hooligan-tinged battle between rivals. The winners adopt him as a sort of comedy mascot, before forgetting him in their drunken haze. Hooligans from their rivals beat EO nearly to death, in a twisted act of revenge. EO has no say in either side of this war, merely becoming a passive and innocent war-ground that humans can exact their primal instincts on.

Treatment of animals is increasingly, cruelly, exposed. Nursed back to health by a vet (a worker at the hospital matter-of-factly asks why they don’t put EO down), he is sold to a mink farm that feels like nothing less than a brutal prison, where animals live in misery until their inevitable skinning to make a scarf. Trafficked across countries with horses, EO is again adopted by a stranger who uses him as a sounding board for his own concerns (this happens arguably three times: Kasandra arguably sees EO’s as a sentimental toy, a drunk unties EO before the fateful football ground because he wants his “friend” to be free and Vito uses him to stave off loneliness). This is as nothing compared to the film’s bleak ending – a terrifying view of the ruthlessness we push animals towards their fate.

EO is so masterful at front-and-centring the experience of an animal, and investing it with immense interpretative empathy, that it means the film actually drags when humans enter the frame. The film feels like it has to include scenes with humans in to bulk up it up to feature length (a better EO would surely be about 60 minutes long). A Polish truck-driver (Mateusz Kościukiewicz) playfully flirts before discovering man is just as inhuman to man as he is to animals. Vito and his mother-in-law, Isabelle Huppert’s countess, play out a small-scale human drama which seems trivial and uninteresting compared to the animal message that dominates the film.

Perhaps this is because EO succeeds so utterly in making us care and even (perhaps) understand the perspective of an animal. It’s a superb act of interpretative art – filmed with an astonishing visual beauty and with a gorgeous score of Pawel Mykietyn – and warm empathetic understanding. It also builds into a surprisingly moving and powerful message on the importance of treating animals with the same dignity and kindness that we would expect to be treated with ourselves. It makes for a thought-provoking and immersive film, that emerges successfully from the shadow of its forbear.

One word. Brutal. But it’s an extraordinary film nonetheless. Great write up.

LikeLiked by 1 person