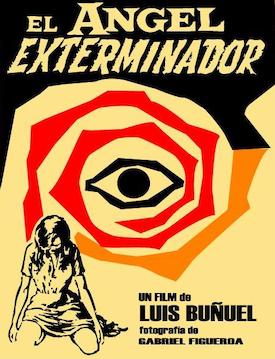

Buñuel’s unique party-gone-wrong is a fascinating mix of comedy, surrealism and satire

Director: Luis Buñuel

Cast: Silvia Pinal (Leticia, “The Valkyrie”), Jacqueline Andere (Alicia de Roc), José Baviera (Leandro Gomez), Augusto Benedico (Dr. Carlos Conde), Enrique Rambal (Edmundo Nóbile), Luis Beristáin (Cristián Ugalde), Antonio Bravo (Sergio Russell), Claudio Brook (Julio), César del Campo (Colonel Alvaro Aranda), Rosa Elena Durgel (Silvia), Lucy Gallardo (Lucía de Nóbile), Enrique García Álvarez (Alberto Roc)

Imagine a party so good, you couldn’t bear to leave. Sounds great, right? Now imagine a party that wasn’t even that good, but you couldn’t leave anyway. A dinner party with the hoi polloi that locks you into a seemingly never-ending parade of days (or weeks) where you and everyone else were physically incapable of stepping over the threshold of the room you’re in. All of you forced to live in a tiny space, on top of each other, none of you having a clue why you can’t leave or why this is all happening. Imagine that, and you’ve got Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel, a surrealist-tinged, open-ended mystery of a film that presents its situation and leaves you to make of it what you will.

Returning to Mexico after comprehensively incinerating his nascent re-alignment with Spanish cinema with Viridiana (a film made in Catholic Fascist Spain that mocked both the fascists and the Church), Buñuel creates a haunting elliptical masterpiece by harnessing an idea so compelling it’s been recycled, reframed and reexplored by countless films after. It’s an idea that has soaked into horror, of being trapped by some unknown force in a single place, unable to break free. It’s also sparked satire with its depiction of the thin veil of smug self-satisfaction over the bourgeoisie that collapses under the strain of covering primitive, violent instincts.

The Exterminating Angel tips us off from the start that we won’t be settling down to watch any old dinner party. As the guests assemble, the staff at the grand town house are practically falling over themselves to flee, as if subconsciously aware there is something wrong in the house. Buñuel throws the viewer off from the start by deliberately repeating scenes – a repetition so on-the-nose, that when watching I actually doubted myself about whether I had just seen what I thought I saw. We see the guests arrive – and make a forlorn call for their coats to be taken – twice in quick succession. It’s so blatant, even Buñuel’s editor gave him a panicked phone call about the ‘error’ just before the film’s opening!

Later the micro-repetitions of scenes, interactions and lines will pile up (it’s a film that rewards constant reviewing) making the whole set-up even more disconcerting. Two characters introduce themselves to each other three times, each time with a different emotional mood (from friendly to outright hostile). The same dinner toast will be greeted with rapture then complete indifference. Two couples will echo the same conversation. Oblique points about freemasonry and current affairs will be made over and over. Is Buñuel suggesting the whole whirligig of the social situation is just a slightly pointless merry-go-round where the same old bullshit happens over-and-over again and essentially means nothing? Sure, the characters notice they are literally trapped in the same room, but really aren’t they just metaphorically trapped in the same old rooms all the time?

Nevertheless, as the dinner party winds down, everyone is far too polite (or far too concerned with appearances) to openly say they feel like its physically impossible for them to cross the threshold and leave. Instead, the hosts quietly grumble that no-one seems to know when to go as the clock ticks into the wee small hours and the middle-class types here settle down in armchairs, on sofas or even on the floor to sleep. Come the next morning, polite embarrassment prevents anyone from saying exactly why they are still here. In fact, everyone promptly makes politely meaningless excuses about why they aren’t quite ready to leave yet: they’ve not had breakfast, nanny will look after their children, they don’t need to be anywhere quite yet.

In fact, I’m not sure anyone openly says they ever feel trapped. It’s like social faux pas everyone is horrified of pointing out. Not a surprise really as everyone here is from the height of professional society: doctors, conductors, army officers, businessmen, society grande dames. None of them wants to stand out like some panicked rube thrown by odd sensations. Instead, everyone slowly settles down into working around this bizarre situation no one wants to talk about. A cupboard is tacitly turned into a toilet. The food is carefully rationed. A water pipe is tapped into so everyone can drink. Sleeping areas are claimed. No one tries to solve the problem, because even acknowledging the problem feels like a cheeky liberty.

It leads into an increasingly fascinating blend of horror, dark satire and surrealist black comedy that Buñuel skilfully builds. A few shots show us the threshold of the room from the next room (a lush ballroom), and there are cuts to a crowd of rubber-neckers outside the house) who also cant enter. But otherwise, it’s all in this one room and as time – and the guests lose all track of that – drags on, the bonds of society both loosen under the polite instincts. Tempers fray, but there remains a formality even as the ravenous guests rip apart (off camera) and cook a sheep that wanders into the room. Some guests take advantage of the proximity to indulge in voyeuristic perversions, but when arguments erupt they are resolved with a Victorian duel mind-set. Only towards the end, as the world really fragments, does the danger of real violence (a suggested lynching of those judged responsible) flare up.

Buñuel would criticise himself later for not going far enough (if you want an idea of relatively tame he later thought it was, he argued cannibalism was one of the things he should have explored). But the fact that much of the behaviour remains grounded, recognisably stuck in a rut of upper-class restraint makes the film more effective. (Or as restrained as a party, where the cancelled ’entertainment’ at the original dinner was an unspecified event involving a tame-ish bear and three sheep, can be). Somehow, if the guests had regressed into the most animalistic behaviour possible, the film might have lost some of its enigmatic quality. As it happens, the fact the guests can never quite escape the trappings of their social rules makes it even more unsettling. It means that threats – such as the ferocity behind the ‘I’ll kill you’ response to a joke about someone being pushed out of the room – carries even more of a shock.

Buñuel throws in the odd surrealistic touch – after all he always claimed a dream sequence was in there when he had run out of ideas. We get two, one revolving about a nightmare of a disembodied hand moving freely around the house (it must be some sort of joke from Buñuel that the hand itself is the least convincing rubbery affair you can imagine) and later a sequence of disconnected images superimposed over a cloud filled sky. The film’s conclusion suggests a deadly, ever-expanding loop, based around the fact the characters suffer but learn nothing from it.

You can argue that The Discreet Charms of the Bourgeoisie, by allowing more physical freedom to its characters, allowed even more surreal, fascinating and intriguing exploration of the repressions, lies and hypocrisies of bourgeoisie life. But The Exterminating Angel has a claustrophobic horror to it, and the pressure cooker bubbling just below the surface of these trapped characters exposes class tensions in superbly unnerving ways. It makes for an expertly executed, shrewdly vicious social satire that lifts a lid on the many petty behaviours that govern so much of our lives. And it’s a mark of genius that you cannot imagine anyone other than Buñuel making it.