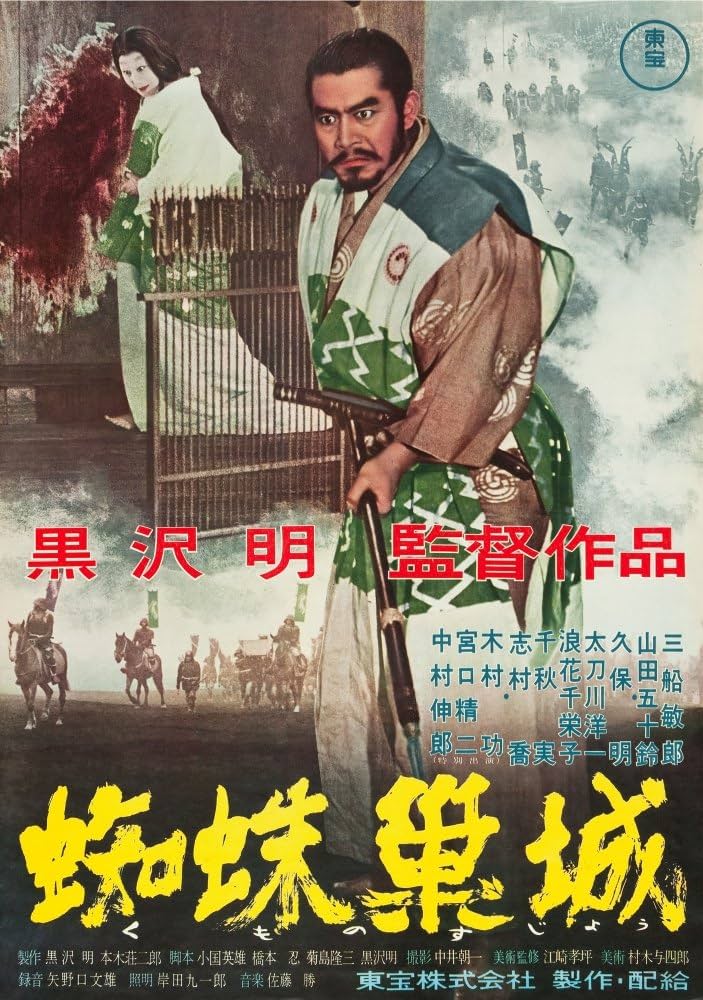

Kurosawa’s Macbeth adaptation beautifully captures much of the spirit of Shakespeare

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Cast: Toshiro Mifune (Taketoki Washizu), Isuzu Yamada (Lady Asaji Washizu), Minoru Chiaki (Yoshiaki Miki), Takashi Shimura (Noriyasu Odagura), Akira Kubo (Yoshiteru Miki), Yōichi Tachikawa (Kunimaru Tsuzuki), Takamaru Sasaki (Lord Kuniharu Tsuzuki), Chieko Naniwa (Forest witch)

Shakespeare is universal. What more proof do you need, than to see Macbeth very much present in Throne of Blood, Kurosawa’s samurai epic version of the Bard’s Scottish play. Kurosawa’s film takes the plot of Shakespeare’s tragedy, with touches of Japanese Noh theatre, told with his distinctive visual eye. It makes for truly great cinema, one of Kurosawa’s undisputed masterpieces – even if it loses some of the greatness of Shakespeare along the way.

You can though see Shakespeare from the beginning in Kurosawa’s mist filled epic (bringing back memories of the Scottish Highlands). A badly-wounded soldier brings news to Lord Tsuzuki (Takamaru Sasaki) of the defeat of his traitorous former friend thanks to the brilliant generalship of Washizu (Toshiro Mifune). Meanwhile, in the forest, Washizu and his fellow general Miki (Minoru Chiaki) encounter a witch (Chieko Naniwa) who prophesies that Washizu will one day be the Lord. When other prophesies proof true, Washizu starts to think how he could make the last true as well. His ambitions are encouraged by his wife Lady Asaji (Isuzu Yamada), who persuades him murder is the best tool for succession. But can they live with the consequences of their crime?

So much, so Shakespeare right? Throne of Blood ingeniously translates Shakespeare’s plot to an entirely different setting, one of feudal Japan. It also translates some of the Bard’s most striking verbal imagery into visuals: the strange mixture of rain and sunshine (‘so foul and fair a day’) that Washizu and Miki wade through before they meet the witch; Miki’s horse thrashing wildly through the courtyard like Duncan’s; the lamps that light the way to Tsuzuki’s chamber (like Macbeth’s dagger). Kurosawa’s visual transformation of the play’s imagery is breathtakingly original.

On its release Throne of Blood was savaged by Western critics for its cheek, before critical consensus shifted to proclaim it one of the greatest of all Shakespeare adaptations. But do you still have Shakespeare without the language (and by that, I don’t mean from English into translation, but its complete removal). Kurosawa’s film makes no attempt to replicate the poetry of Shakespeare (most strikingly, its equivalent of the “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” speech is Washizu shrieking “Fool! Fool” as he sits in frustration, a neat image but one where you’d wish Mifune had been given more to play). But Throne of Blood may not be a complete Shakespeare adaptation, but it’s possibly one of the greatest adaptations ever made of a Shakespeare story.

This is because Throne of Blood captures so many of the core thematic concepts of Macbeth, not least its destructive, nihilistic force and the terrible, crushing burden self-imposed destiny and ambition sets. Toshiro Mifune’s Washizu may more of a brute than Macbeth, but his blustering, aggressive exterior hides a weak man, insecure and dependent on others. His weakness is in fact a lack of imagination, his inability to picture a life outside of the tracks laid down before him by the witch. His lack of independent thought is recognised by his wife, Asaji who nudges and pushes Washizu in the direction she (and he, deep down) wishes at every opportunity.

Washizu is soon trapped in a cycle of murder and disgrace he can’t escape. The walls of the room where he and Asaji plot the murder of Lord Tsuzuki is still smeared with the blood from the seppuku of its former owner who also betrayed Tsuzuki. Whenever he enters the forest, Washizu seems almost wrapped inside its branches, unable to find his way. Before a dinner to host the murdered Miki, Washizu listens (like Claudius) to a noh actor recount details of a crime all too similar to his own. As Lord, Washizu cowers powerlessly in it just as its previous owner did. Even the film itself is a grim cycle of the inevitability of destruction: Kurosawa’s open mist rolls away to reveal a monument to the castle before the castle itself emerges to take its place, the film returning at its end to the same mist-covered monument. These bookends also stress how transient (and pointless) this grappling for power is – nature will eventually claim all.

But it also suggests a world where death is so inevitable, that you might as well seize what power you can when you can. Even Miki – the film’s finest performance from Minoru Chiaki, full of subtle reactions of resignation and disgust – turns a blind eye (despite his sideways glances of disgust at key moments) to Washizu’s crimes, to further his son’s promised hopes for the throne. Asaji is motivated by her belief that there is no sin in seizing what you can from our brief time in this world, firmly telling Washizu that not only is it his duty to deliver the prophecy but – in a world where Tsuzaki gained power by murdering the lord before him – he would hardly be the first and that no previous killer trusts a potential new rival in any case.

Asaji is strikingly played by Isuzu Yamada, a quiet, scheming figure who sees everything and has an inner strength her husband lacks. Like Mifune, she uses the striking poses of Noh theatre to fabulous effect – Asaji herself moves, on the night of the murder, in a noh dance craze – and to communicate the dance of power between them throughout that long night. Kurosawa also uses silence beautifully with Asaji, most strikingly of all her silent, almost supernatural, collecting of drugged saki for Tsuzaki’s guards: as she walks into, disappears into darkness, then reappears carrying the drink all that is heard is the squeak of her robes across the floor. Yamada’s controlled, Noh-chill makes her brief collapse into futile hand-washing madness all the more striking.

After the long night of the murder, Kurosawa presents a world that grows more and more uncontrolled. In a brilliant innovation, Asaji provokes the murder of Miki by lying (perhaps?) about being pregnant, making Washizu desperate to protect the chance of a royal line. Miki’s murder leads to his terrifying pale ghost silently challenging an increasingly wild Washizu, who thrashs weakly around the room seemingly without any control. Mifune’s powerfully gruff Washizu becomes increasingly petulant and desperate, lambasting his troops and clinging to the letter of the prophecies rather than their more detailed meaning. Mifune’s striking poses – inspired by noh theatre – seems to trap him even more as hyper-real passengers in a pre-determined story. If Kurosawa’s adaptation has rinsed much of their complexity out, he firmly establishes the couple at its centre as trapped souls in an inescapable cycle.

Kurosawa innovates further by introducing a sort of Greek chorus of regular soldiers, ordinary warriors under Washizu’s command whose faith in their commander (they clearly know he murdered Tsuzaki) shrinks as Washizu’s grip on the situation fails. Washizu clings to belief in his invulnerablity – even after the prophecy about the impossible circumstances needed for his defeat (as if a forest can ever move!) is told to him in a fit of mocking laughter by the androgynous witch and a string of suspicious woodland spirits.

It culminates in Washizu instigating his own destruction, bragging to his men about the obscure circumstances that will lead to his defeat – leading to his own disillusioned men fragging the panicked lord the second the situation comes to pass. Kurosawa’s ending is visually extraordinary, Washizu pierced with so many arrows he resembles a human porcupine (Mifune’s terror was real, the actor dodging real arrows). Just as Asaji collapses into madness, Washizu’s fate is ignoble – Kurosawa doesn’t even afford him Macbeth’s brave duel against Macduff, this great warrior instead going down without so much as inflicting a scratch on Throne of Blood’s Malcolm and his forces.

Throne of Blood focuses beautifully on some (not all) of the key themes in Macbeth. It presents a fatalistic world where choices are few and the deadly cycle of death never seems to stop. Kurosawa interprets this all beautifully, transferring Shakespeare’s verbal imagery into intelligent, dynamic imagery. Sure, in removing the text it removes the core thing that makes Shakespeare Shakespeare – and also leads to the simplifying of its characters, in particular its leads who lose much of their depth and shade. But as a visual presentation reinvention of one of Shakespeare’s stories, this is almost with parallel, a triumphant and gripping film that constantly rewards.