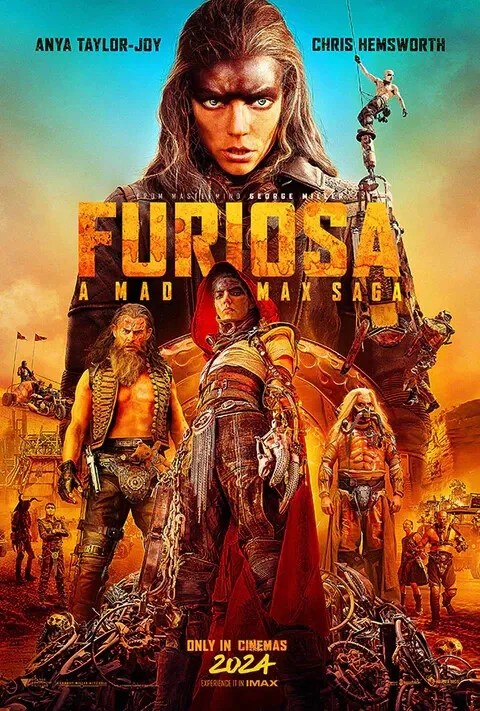

Deliriously overblown and full of demented imagination even if it never quite feels necessary

Director: George Miller

Cast: Anya Taylor-Joy (Furiosa), Chris Hemsworth (Dementus), Tom Burke (Praetorian Jack), Lachy Hulme (Immortan Joe), Alyla Browne (Young Furiosa), George Shevtsov (History Man), John Howard (People Eater), Angus Sampson (The Organic Mechanic), Nathan Jones (Rictus Erectus), Josh Helman (Scotus), Charlee Fraser (Mary Jabassa), Elsa Pataky (Mr Norton)

Is there a more demented mainstream film series than Mad Max? Furiosa follows the balls-to-the-wall excess of Mad Max: Fury Road with more of the same and a mythic atmosphere of Godfather Part II-backstory deepening. What you end up with might feel slightly odd or self-important – over two and a half hours of direct build-up for a pay-off we saw almost ten years ago (perhaps that’s why Furiosa ends with a cut-down play-back of the major events of Fury Road spliced into the credits, so we can all be reassured the villains left alive here got their comeuppance later). Furiosa is frequently overlong, a little too full of its love of expansive world-building and never quite convinces you that we actually need it – but then it’s also so bizarre, Grand Guignal and totally nuts perhaps we should just be happy that, in a world of focus-grouped content, it even exists.

We’re back on the desert wasteland of post-apocalyptic Australia as motorbike riding goons kidnap young Furiosa (Alyla Browne) from the Green Place hoping to use her to persuade crazed war lord Dementus (Chris Hemsworth) to lead his forces there. Despite the heroic efforts of her mother (Charlee Fraser), Furiosa remains a captive with only a secret tattoo on her arm (guess what’s going to happen to that…) to guide her home. Dementus provokes a resources war with cult-leader Immortan Joe (Lachy Hulme), with Furiosa traded, then escaping a hideous fate as one of Joe’s wives, instead growing up secretly-disguised as a boy (becoming Anya Taylor-Joy) as part of Praetorian Jack’s (Tom Burke) War Rig crew. Then the war between Immortan Joe and Dementus explodes again, foiling Furiosa and Jack’s plan to escape and giving Furiosa a change at revenge against Dementus.

That sprawling plot outline hopefully gives an idea of the ambitious bite George Miller is taking out of his world. While Fury Road took place over, at most, a few days, Furiosa stretches well over twenty, so gargantuan in scale and newly invented locations (as well as the mountainous citadel, we get the oil-rig nightmare of Gas Town and the Mordor-like Bullet Town) that it squeezes most of the entire Act Five war between Dementus and Immortan Joe into a brief, tracking-shot, montage. Furiosa is actually rather like a fever-dream Freud might have had after reading an airplane thriller, split into on-screen chapter titles – each with portentous (and sometimes pretentious) names like ‘The Pole of Inaccessibility’ – and a self-important narration dialling up mythic importance. If Fury Road was like someone stabbing an adrenalin-filled syringe straight into your heart, Furiosa is a like being told a detour-crammed story by someone a bit the worse-the-wear after a long night.

Not that Furiosa shirks on the banging madness of Fury Road’s slap-in-the-face action. It features a mid-film War Rig vs motor-bike raiders pitched-driving battle that is so extreme you wonder no one got crushed under wheel while making it, perfectly capturing the addled madness of Fury Road. A Chapter 4 pitched battle at one of Furiosa’s Dystopian-on-speed locations sees destruction, devastation and disaster on an even grander scale than anything else Miller has done before in this series, with an entire mining crater turned into a whirligig of firey destruction. That’s not forgetting three desperate desert chases – the finest of which is the film’s opening sequence, which see Furiosa’s mother track down and ruthlessly dispatch Furiosa’s kidnappers with a velociraptor-like ruthlessness and efficiency. No wonder Miller can put a whole war into a single shot – and why he feels comfortable ending Furiosa with a surprisingly personal and small-scale confrontation.

The main confrontation is between Furiosa and her self-proclaimed warlord – and would-be surrogate Dad – Dementus. Furiosa gives Chris Hemsworth the opportunity he’s been waiting for, allowing to flex his comic muscles, chew hilarious lumps out of the scenery and still show his menace. He makes Dementus an overgrown child, brilliant at stealing but with no idea about how to use them, obsessed with self-improvement (his dialogue is full of verbose, overwritten phrases, like a psychotic thesaurus) and only really happy when he’s smashing something. Introduced framing himself like a zen-like messiah, it doesn’t take long until he’s charging around on a chariot drawn by motorbikes, tasting other people’s tears and giving self-aggrandizing speeches while torturing Furiosa’s nearest-and-dearest. It’s a gift of a part, funny, scary, loathsome but strangely likeable even when he does awful things.

Opposite him, Anya Taylor-Joy actually has less to work with as Furiosa (she only takes over the part almost an hour into the film). Although this is meant to be a Furiosa film, it rarely feels like its telling us much more than we already know, especially since much the skills that ‘makes’ Furiosa what she is in Fury Road takes place in montage and her desire for freedom and to protect others are swiftly established so that any new-comers can unhesitatingly root for her. If Dementus is all talk, Taylor-Joy’s Furiosa is silent and simmering, her humanity either shrinking or quietly growing from moment-to-moment. She has a quiet romance with Tom Burke’s world-weary Praetorian Jack, but this really about converting her into a mythic figure of vengeance rather than making her a personality.

A vengeance we’ve already seen pan-out in Fury Road. I’ll be honest, for all the grand scale of Furiosa, I don’t really feel I learned anything about its central character here I hadn’t already picked up from Theron’s brilliantly expressive performance in the first film. For all the impressiveness of the scale, a lot of Furiosa boils down to physically showing us things that were implied in the first (second?) film – from locations, to the reasons why Furiosa lost her arm to giving us clear reasons for her motivations. But all this is already there – and with brilliant economy – in Fury Road. Telling us all again feels like Miller giving us the footnotes (Furiosa Silmarillon perhaps?) rather than anything truly new and the Homeric backdrop Miller is going for never really clicks into place.

So the most successful swings are not narrative but visual. Furiosa reminds you what an absolutely insane extreme world Mad Max is. Death cults of radiation-deformed albinos? Villains who bottle milk straight from the nipple (not a cow’s), while another obsessively fondles his exposed, pierced ones? A villain who straps a battered old Teddy bear to himself? Action set-pieces that throw in everything – flying bikes, lava lakes and arms stoically lopped off? Even time-jumps are done imaginatively, like a wig, caught in a branch, decaying in front of our eyes. Every single design decision in this – and the gorgeously sun-kissed photography – is dialled up to eleven for George Miller’s very personal vision of pulpy, dystopian chaos.

You can wonder at times – as I did – whether we really needed a two-and-a-half hour film that’s expands the thematic depth of a chase movie which already outlined its characters motivations and personalities with impressive economy. But then, there are moments in Furiosa that just feel like they’ve been pulled out of someone’s crazy dreams. It’s put together with such a good mix of pulp poetry and head-banging craziness by George Miller that after a while you just go with it. And it sticks with you in a way focus-grouped Marvel films never seem to.