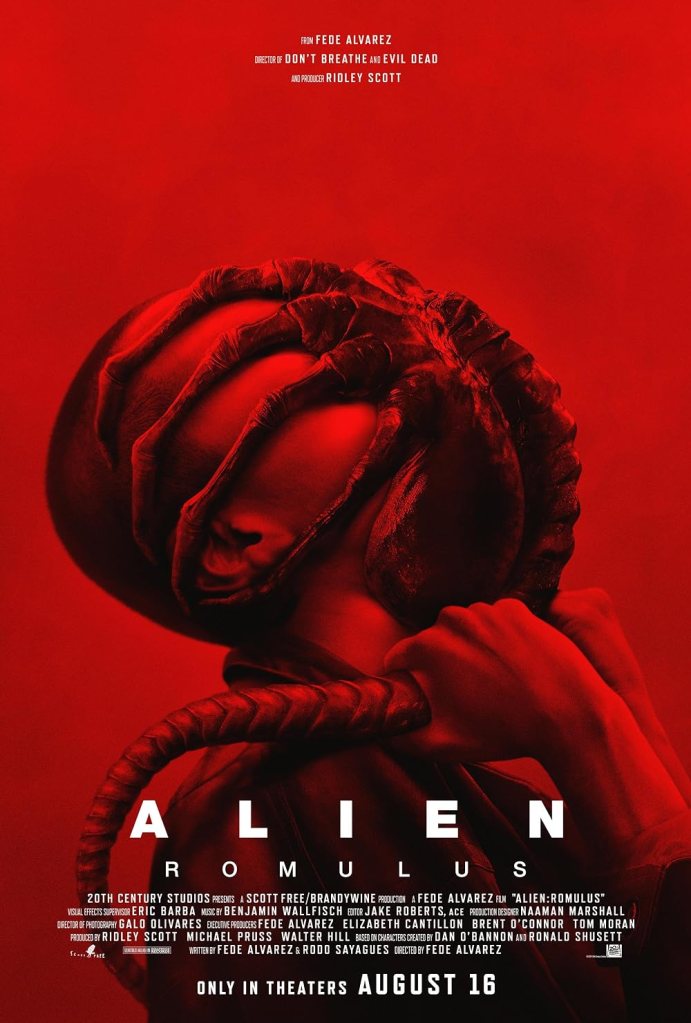

Starting as a cleverly structured homage, it becomes increasingly more nostalgia driven as it goes on

Director: Fede Álvarez

Cast: Cailee Spaeny (Rain), David Jonsson (Andy), Archie Renaux (Tyler), Isabela Merced (Kay), Spike Fearn (Bjorn), Aileen Wu (Navarro), Daniel Betts / Ian Holm (Rook)

It’s always a surprise how many Alien films there actually are (at least nine if you count all the Alien vs Predators). Perhaps we forget because so many of them have been less than great. So, saying Alien: Romulus is the third best Alien film isn’t exactly high praise. After all, beyond Alien and Aliens the bar is pretty low. Alien: Romulus has a lot going for it, not least the fact it’s clearly been made with love by a director who adores the series. It makes it all the sadder that, the longer it goes on, the more it becomes a fan-boy remix of a elements from the other films. It ends up as much of a nostalgia obsessed, easter-egg piece of fan bait as any recent Marvel film, but at least entertaining.

Set some time after Alien – it opens with a mysterious Weyland-Yutani ship plucking the original Xenomorph (wrapped in a protective cocoon) from the Nostromo’s wreckage– ourhero is Rain (Cailee Spaeny), a young worker in a grim mining facility planet. Working for credits for passage home – a target the company constantly changes – she lives with her adoptive ‘brother’ Andy (David Jonsson), a gentle, glitchy synthetic reprogrammed by her late father. They have a chance for freedom when her ex-boyfriend Tyler (Archie Renaux) and his crew asks her and Andy’s help to plunder cryostasis chambers from an abandoned ship so they can survive the nine-year journey to another world. But the ship (Romulus and Remus) is, of course, the one we saw earlier – and on board are a host of facehugger experiments, leading inevitably to Xenomorph slaughter.

Alien: Romulus starts very strongly, carefully reconstructing the stylistic look and feel of the original (right down to the spot-on sound design of all those 70’s future computers blinking into life, chuntering old fax machines). The crapsack colony feels perfectly in-tune with Aliens, as a mix of Western frontier town and industrial hellscape. Álvarez’s film brings the franchise back to its roots, after the mystique-shattering of Ridley Scott’s prequels. Romulus is a haunted house in space, a psychopathic alien lucking around every corner. As the tension slowly builds – helped by the fact we, obviously, know a lot more about what those odd spidery-things suspended in animation are – Alien: Romulus feels like a return to the factors that made the series work in the first place.

Álvarez dials up the sexualised body horror of this revolting creature and its unstoppable relentless cunning. Alien: Romulus is full of the revolting invasiveness of these animals, the icky body horror of creatures hatching inside you, with the nightmare-fuel monstrosities getting worse as the film goes on. Playing out in a poorly lit ship, the creatures scuttle from the corners of the screen to impregnate or dissect their victims. He also has some neat original ideas, including deducing the face-huggers detect body heat and movement (having no eyes) so the only way to evade them is to raise the room temperature and move slowly (such a good idea, you wish he made more of it).

It’s also a film that looks at the all-round weapon nature of these creatures, specifically their acid blood. The team can’t shoot the things – they’ll melt through the decks and cause instant decompression – and when one does die, its blood floats through zero-gravity as an almost impossible to evade thread. One character dies not from the jaws of the xenomorph, but from sticking a cattle prod into its cocoon, acid spilling out into his eyes, hands and chest (not pretty).

It’s opening act also offers an intriguing relationship between its two leads, one a potential proto-Ripley with a strong moral compass, the other a very different type of synthetic. Andy, well-played by David Jonsson, is gentle, clumsy and naïve, a vulnerable people-pleaser who loves cringy Dad jokes, prone to the android equivalent of epileptic fits under pressure. By establishing the closeness between these two characters, Alien: Romulus explores a new angle of the series study of the relationship between humans and their creations: are these synthetics people or property?

Rain clearly loves Andy: she may resent the bullying he receives from some of the anti-synthetic crew, but also willingly reprograms him when needed and plans to leave him behind so as not to fall foul of anti-synthetic laws back home. Reprogramming Andy drastically alters his personality – David Jonsson does a great job switching his body language, demeanour and accent (back to his native British) – as Andy becomes a more familiar Alien electric reflexes and ‘needs-of-the-many’ andriod. What’s intriguing here is its implied part of this is due to Andy’s own suppressed resentment at his treatment by the humans as somewhere between a child and a screwdriver.

The complex relationship between these two is the heart of Alien: Romulus and its most original element. It’s a shame the film loses focus on this the longer it goes on. As Romulus hits it’s second half, Álvarez succumbs to fanboy temptation until finally he can’t go more than thirty seconds without referencing an line or scene from an earlier Alien film. Slowly the parade of painfully recognisable features (even an utterly out-of-character reprise of ‘Get away from her you bitch’) begins to depress you as Alien: Romulus gives up the idea of being something fresh and settles for being a passionate piece of fan-fiction, unable to imagine anything beyond the scenarios it’s already seen play out somewhere else.

Alien: Romulus becomes as much a nostalgia trip as anything else Hollywood makes these days. Right down to recreating a digital version of the late Ian Holm as ‘Rook’, Romulus and Remus’ version of Nostromo’s Ash, for a prominent role. The recreation is pretty good, Rook is an interesting character – sympathetic to the heroes at first, but increasingly reverting to form – but there is something uncomfortable about it. This is, after all, a recreation for nostalgia of a dead actor, without his consent (though with his families) not as a visual cameo but as a crucial character. How long before we get more and more of this?

It’s a slightly unsettling note, even if I ended up enjoying Alien: Romulus more than a should have. Part of me liked seeing Ian Holm again. Hypocritically I don’t mind quite so much riffs on films I like –hypocritical since I was annoyed by the same thing in Deadpool & Wolverine. But I wish Alien: Romulus had settled for subtle recreation of details while striking out somewhere unique. What it actually ends up doing is suggesting that, once you strip it down to its roots, there isn’t much to Alien beyond slasher-in-space. Which makes you think, for all its flaws, perhaps Prometheus was a braver movie for trying to do something that wasn’t that.

But then I’ll also definitely watch it again. So maybe that makes me part of the problem.