Early talkie gives a melodramatic insight into a Victorian stateman, with an Oscar-winning star turn

Director: Alfred E. Green

Cast: George Arliss (Benjamin Disraeli), Doris Lloyd (Mrs Travers), David Torrance (Lord Probert), Joan Bennett (Lady Clarissa Pevensey), Florence Arliss (Lady Beaconsfield), Anthony Bushell (Lord Charles Deeford), Michael Simeon Viscoff (Count Borsinov)

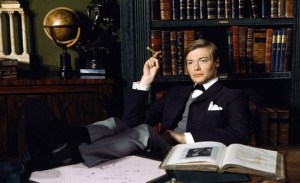

Based on an Edwardian melodrama, Disraeli was the sound debut of George Arliss, a highly acclaimed British actor with a successful silent career. Unlike other silent actors, Arliss’ theatre training made him ready made to have his voice be heard around the world and his Oscar for Best Actor saw him ride the crest of the sound wave. Today, the film looks inevitably quite primitive, so careful to get the sound recorded that its camera barely moves from its fixed position in the ceiling-free sets. But Disraeli, for all this, is rather entertaining if you settle down to it despite its stodgy set-up still deeply rooted in its Edwardian melodrama roots.

It’s odd to read some reviewers describing Disraeli as a dry history lesson: there is almost nothing historical about the plot of Disraeli. While Disraeli did arrange the purchase of a controlling share in the Suez Canal, I can assure you he did not do it while dodging Russian spies in his own home, balancing a series of daring financial moves, laying cunning traps for scheming Russian agents or playing match-maker for his young protégé. Far from a history lesson, Disraeli is really a sort of Sherlock Holmesish thriller, with Disraeli recast as a twinkly wise-cracker constantly several steps ahead of everyone else. It’s a playfully silly set-up rather disconnected from history – and certainly far more fun than the actual dry history of financial and diplomatic negotiations.

Disraeli is a surprisingly well-scripted (as far as these things go) play, which mixes some decent jokes and creative set-ups with a liberal use of phrases from the eminently quotable Disraeli himself. You can’t argue with the wit of Disraeli (the man famously had dozens of entries in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations) and the film bounces several bon mots around (‘That’s good. Perhaps I’ll use it with Gladstone’ Disraeli even comments on one of his own lines). There is wit in other moments, not least Lord Charles’s (Anthony Bushell) proposal to Lady Clarissa (Joan Bennett) which dwells so much on his charitable good works rather than any affections that Lady Clarissa is moved to comment she expected a proposal “not an essay on political economy”.

You can see its melodramatic roots all the way through. Secret talks about the canal are held in Disraeli’s house, in open earshot of a Russian spy Lady Travers (Doris Llloyd), who we later discover Disraeli is carefully leading on. Like a cunning Edwardian detective, Disraeli role-plays illness at one point to delay Lady Travers and resolves a last minute disastrous collapse in his payment scheme for the Suez shares with a swaggering bluff that he delightedly tells his amazed allies about the moment the duped Governor of the Bank of England (forced against his will to back the scheme) leaves the room. All this in a largely single-room setting: this is pure Edwardian theatrical melodrama bought to screen, not history.

It’s similar in its picture of history, here re-worked to position Disraeli as the sort of maverick hero we can immediately recognise from films. Disraeli is established as an outsider who no one in the establishment trusts (never mind he was the leader of the firmly establishment Conservative party, or that his rival Gladstone was seen by the crusty banker types in this film not as their saviour but as a dangerous radical). Despite being referred to as Lord Beaconsfield several times, he sits in the commons to face down Gladstone (an uninspired cameo by an unbilled actor). He is displayed as the sort of negotiating and diplomatic genius whose insights can only be responded to in wonder by Lord Charles, his dim Watson.

Like Sherlock Holmes, he lavishes Charles with backhanded compliments (specifically that his rigid honesty makes him the perfect agency for a secret mission because no one could believe he was up to lying). Like many Edwardian theatrical leads, he’s also an intense romantic. Not only deeply in love with his wife (played by Arliss’ wife Florence) but also at least as interested in making sure Charles and Clarissa end up happily married. Arguably none of that relates to the real Disraeli, a largely scruple and principle free opportunist with more than a few similarities to Boris Johnson (but with a sense of personal honesty and decency, Boris can only dream of).

The main point of interest today is George Arliss’ performance. For all its clearly a version of his stage performance, it’s still very engaging and charismatic. Arliss may deliver some of his lines like they are theatrical asides, and his mugging to a non-existent audience in Disraeli’s fake fitness is (while funny) clearly something that worked much better on stage. But he is twinkly, captures the shrewd intelligence of Disraeli and utterly convinces as a man who could run circles around everyone else. Arliss invests both the speeches and the dialogue with a genuine playful wit and a heartfelt honesty which works very well.

It’s entertaining and he looks very comfortable in front of the camera and he’s head and shoulders above the rest of the cast in terms of the light-and-shade he gives the dialogue. While the rest of the cast deliver their lines with the sort of forced formality that focuses on making sure the mic picks up every word, Arliss performs his lines. He’s got a sharp sense of comic timing, wheedles and boasts with real energy and isn’t afraid to chuck the odd line away. It’s a sound performance probably years ahead of its time.

The rest of the film is very much of its era. Green’s direction is incredibly uninspired. The camera set ups are very basic. The problems of sound can be seen throughout: from the awkward positions and formality of the camerawork to the occasional line flub that creeps into the soundtrack. Disraeli can look a lot like a filmed play, largely because it’s been set-up with such little focus on visuals. It’s reliance on title cards between scenes shows how fixed it still is on the clumsier parts of silent film-making. You could say, without Arliss, there would be very little to actually recommend it, for all there is the odd good line. But with him, it manages to be a little bit more than just a historical curiosity.