Director: George Roy Hill

Cast: Paul Newman (Henry Gondorff), Robert Redford (Johnny Hooker), Robert Shaw (Doyle Lonnegan), Charles Durning (Lt William Snyder), Ray Walston (JJ Singleton), Eileen Brennan (Billie), Harold Gould (Kid Twist), John Heffernan (Eddie Niles), Robert Earl Jones (Luther Coleman), Jack Kehoe (Erie Kid), Dimitra Arless (Loretta Salino), Sally Kirkland (Crystal)

From its opening, to the ragtime charm of Joplin’s The Entertainer, it should be pretty clear what you are in for with The Sting. A nostalgia-tinged star-vehicle, The Sting is gloriously unpretentious, a film that means only to entertain. Charming and good-natured, you can forgive it an awful lot because it wants so little from you: other than to put a smile on your face (a real “aw shucks I never saw that coming!” grin). A slice of pure entertainment, with more than a hint of nostalgia, it hoovered up seven Oscars (in an admittedly weak year – its nearest competitor was The Exorcist and it says something for how eclectic American cinema can be that those two films hailed from the same year) at a time when the nation needed a lift.

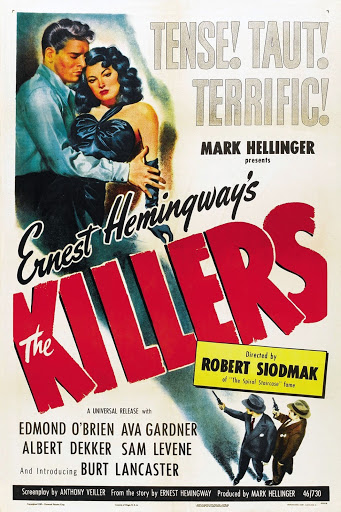

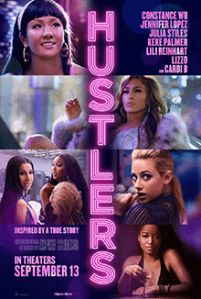

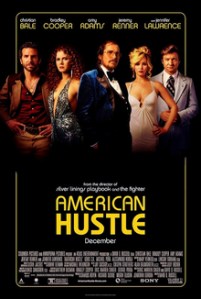

The Sting is perhaps the ultimate confidence-trick, caper movie. It’s been effectively remade so many times (it’s basic plot was copied exactly for the first episode of BBC’s confidence trick dramedy series Hustlers among others) it’s likely that you will recognise some of its tricks long before viewers at the time did. But that doesn’t really matter, because like all tricksters, it tells a great story. In 1930s Illinois Johnny Hooker (Robert Redford) is a grifter who makes a score off the wrong guy: a courier for vicious crime boss Doyle Lonnegan (Robert Shaw). In the violent aftermath, his partner and mentor Luther (Robert Earl Jones) is murdered. Hooker heads to Chicago to partner up with famous grifter Henry Gondorff (Paul Newman) to get his revenge. The plot comes together – but can they stay ahead of Lonnegan, the cops (led by Charles Durning’s Lt Snyder) who are after Hooker and the FBI who are hunting Gondorff? Or will they fool everyone?

Well what do you think? Directed with a professional (Oscar-winning) smoothness by George Roy Hill, this is basically Butch and Sundance Go Grifting. The film follows pretty much exactly the same nostalgia soaked journey following two charming Hollywood mates thumbing their nose at authority. The recreation of the period is extremely detailed (it won Oscars for production design and costumes), but above all safe and cosy. For all that it grifts in the rough-end of town, it’s a very clean and uncrowded world (the street scenes are notably empty) and very little reality is allowed to get in the way of what is effectively a shaggy-dog story.

The vision of the past it presents is designed from top-to-bottom to be comforting and the film is devoid of any sense of danger connected with grifting, or any sense of moral complexity around people who make their living from conning others. It’s a world where the only people conned are them-what-deserves-it and the conmen are plucky underdogs, making a buck off the crooked big man while fighting the corner of the little guy. It basically repackages conmen as fairytale heroes – and does so, so successfully most conmen films since have followed its lead.

It’s fairy-tale style is carried across in the chapters (with some lovely nostalgic hand-drawn chapter opener pages) that the film is split into, not to mention the structure of a callow youth, a rough but wise mentor, a hissible villain and righteous mission. The only thing it really misses is a princess to save (although there is the gentlest femme fatale you’ll ever see). But then there isn’t really room as, even more so than Butch and Cassidy this is a bromance played out in the same sepia-toned “good-old-days” warmth.

Newman and Redford are of course huge fun, using every inch of star-power gusto and cool. Newman has great fun as the sort of cigar-chomping, hard-drinking maverick only ever seconds away from bounding up from a scruffy sleep to perform all manner of tricks with assured cool. Newman generously cedes most of the richer material to Redford, but he can hardly have minded when he gets such glorious set-pieces as his faux-drunken card-sharp routine when he muscles in on Doyle’s cross-country train card game. I’ll also give a shout out to a wonderful moment when Gondorff goes through an elaborate show-off run-through of his card-sharp skills – only to get over-confident and spill the deck. It’s a good laugh, but also adds a little beat of tension (needless to say he performs flawlessly on the night).

Redford got his only acting Oscar-nomination here and, while it’s not his most challenging role, it’s certainly one where his magnetic Hollywood charm was used to its best effect. He gets the meat of the plot, walking a difficult line between being both an audience surrogate and keeping us uncertain about how much of what we are seeing is true. Redford’s handsome boy-next-door charm works perfectly for Hooker – and he’s got a sweet shocked horror at violence when it comes – and he has a rather winning naivety mixed in with a youthful energy. Sure, it’s hardly Hamlet, but as a riff on his WASPY version of counter-culture cool, it’s pretty much spot-on. (Redford is also of course a very safe presence – there’s nothing dangerous to him, which is of course perfect for the film’s tone.)

These two energetic and charismatic performers – both having a whale of a time – are the main selling point of a movie that rattles through fun set-pieces. Like all the best con movies, it lays out all its pieces and only assembles them all into a picture right at the very end. It makes for something little more than a fairground entertainment – Marvel as Gonrdorff and Hooker Hoodwink a Man Before Your Very Eyes! – but when it’s told with such zip, charm and lightness as this it hardly matters. Even the heavy – a growling Robert Shaw – gets a bit of light-banter under the menace (“What was I supposed to do” he bemoans after Gondroff swops out the crooked cards he’s dealt him “call him for cheating better than me?”).

The Sting isn’t trying to reinvent the wheel or tell you anything serious. It just wants you to grin. While we might be told grifting can be dangerous, the main impression of the film is that it’s matey boys-own blast. And it wants us to enjoy the entertainment as much as the conmen do. It knows that, like a good magic trick, we love to see how the illusion works and there are few things more engrossing than watching professionals execute a difficult task flawlessly. It’s one of the lightest Best Picture winners, but then it’s also one of the most purely enjoyable.