|

Daniel Day-Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer have a love that cannot survive the morals of society in The Age of Innocence |

Director: Martin Scorsese

Cast: Daniel Day-Lewis (Newland Archer), Michelle Pfeiffer (Countess Ellen Olenska), Winona Ryder (May Welland), Miriam Margolyes (Mrs Mingott), Geraldine Chaplin (Mrs Welland), Michael Gough (Henry van der Luyden), Richard E. Grant (Larry Lefferts), Mary Beth Hurt (Regina Beaufort), Robert Sean Leonard (Ted Archer), Norman Lloyd (Mr Letterblair), Alec McCowen (Sillerton Jackson), Sian Phillips (Mrs Archer), Jonathan Pryce (Rivière), Alexis Smith (Louisa van der Luyden), Stuart Wilson (Julius Beaufort), Joanne Woodward (Narrator), Carolyn Farina (Janey Archer)

In 1870’s New York, Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis), is a fastidious connoisseur of the arts, part of the super-rich elite of New York society. He’s engaged to be married to young May Welland (Winona Ryder), but finds his world view and values turned upside down when he meets May’s cousin, the Countess Ellen Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer). Ellen is a scandalous figure, a woman separated from her philandering European husband, trying to make her way in New York society. Newland and Ellen are irresistibly drawn together, but do they have a chance to be together in the oppressive society of the New York upper classes?

That’s one question. The one more people were asking was: how would Scorsese follow up Goodfellas? Probably very few people would have bet on an adaptation of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence. In fact, in 1993, there was more than a little annoyance among some viewers at the idea of the master of gangster movies, the guy who directed Raging Bull and Taxi Driver, turning his hand to the realm of Merchant Ivory. The film bombed at the box office – but did it deserve that reaction? Was Scorsese a director out-of-place?

Well the reaction is slightly unfair, because The Age of Innocence is a marvellously filmed, exact, brilliantly constructed piece of film-making, that so lays on the opulence and wealth of New York society that it turns everything in the film into feeling like a gilded cage. That’s a cage carefully controlled and monitored by the inmates, with their strict, inflexible rules about every single social interaction, unbreakable rules of decorum and etiquette covering everything, with any deviation from these rules met with instant expulsion. Put it like that, and this doesn’t sound a million miles away from the gangster families Scorsese is more associated with.

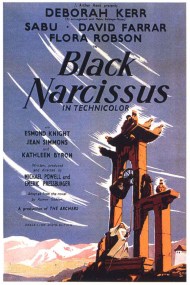

Inspired by the films of Powell and Pressburger in its intricate construction, and flashes of artifice in filming and editing, as well as its rich colour palette, with touches of everyone from Visconte, Ophüls, Truffaut to name but a few, this is a film-maker’s love letter to cinematic classics. A beautiful sequence of Newland watching Ellen from behind and a distance on a jetty, yearning for her to turn around before a boat passes a lighthouse, using that landmark as the point when he will stop looking and accept something is not to be. The scene is bathed in a Jack Cardiff-ish red, with the objects in the light given a sharp definition in contrast to the colours. It’s a beautiful image, and one of several that run through the film. Inspired by paintings of the era, Scorsese also layers in Viscontish scenes of opulence, with The Leopard very much in mind as every detail of the vast wealth, and huge accumulation of objects in every room of these people’s houses, seems to crush and entrap the people in them. The rooms themselves become metaphors of the oppressive, rule-bound society the characters are trapped in, like the people have been designed to fit into the rooms rather than vice versa. The one exception is Ellen’s rooms, which have a sense of personality to them.

This marvellous construction – with its beautiful photography, inspiring design and costumes – contains a storyline of frustrated love, a love triangle between three people where the man has to make a choice between what he wants and what is expected of him. Newland Archer clearly loves Ellen in a way he can never love May – indeed, he is dismissively cruel in his thoughts towards May, who he clearly considers nothing more than an extension of the mindless gilded objects of beauty around him, a woman he sees as lacking an imagination or daring. In Ellen, he sees far more opportunities for a world of change, of difference, or being something he does not expect. She is far more of a free-spirit, a more bohemian figure, confident in herself and something far more modern than May, who is very much a product of her time and place.

The film, carefully demonstrates the growing unease and unsettlement of Archer as he begins to feel things he has never done before, to start to react and aim for a style of living he would never previously consider. All his life before now is a careful studying and collection of moments, or savouring experiences in the way that a collector would place them in a glass box. From seeing only the moments of plays he wishes to see, to carefully collecting shipments of books from London and reading the choice moments, Archer is a coldly controlling figure who believes he guides and directs his own life. Ellen not only demonstrates to him that in many ways he is as conventional as anyone else, but also that there are other options in his life. Archer struggles to build the emotional language that he needs in order to express these feelings bubbling in him – key moments indeed seem reminiscent of the operas that this New York society spends so much time watching, and it is only late in the film in little, genuine moments of affection can he find something real.

Scorsese’s film artfully and carefully shows this developing affection between the two, a love that the two of them speak of surprisingly early, but fail to find a genuine way of expressing it. The film captures the attempt by New York society at the time to be more British than the British, and the hidebound restrictions this brings. Scorsese uses cinematic tricks to show Archer’s striving to escape. Spotlights zero in on Archer and Ellen in the middle of society, as if to drain out all other moments. Letters from his respective love interests are delivered with the actors addressing the camera, as if speaking to Archer direct. Flashes of screen colour cover key cuts, as if all this colour was just on the edges of his life but he is unable to access them. He is a man who feels himself trapped and committed to one form of life, but who still feels the longing for another.

The Age of Innocence is a beautifully made film, but there is a coldness to it. Perhaps this is why it doesn’t quite capture the heart in the way of other films. So much as Scorsese captured the cold and restrictive world of this society, that it seems to permeate the film and make the whole thing somehow colder and more restrictive. There is such artistry and effort in the film-making, that the film seems a coldly detailed piece of art. Perhaps this is why the use of narration – beautifully spoken by Joanne Woodward – becomes overbearing here in the way it doesn’t in other Scorsese films. It’s another distance from the entire experience, as if the film is keeping the audience at arm’s length as much as society is.

Daniel Day-Lewis’ performance is expertly assembled, a masterful, brilliantly observed, intricately detailed masterclass in micro-expression, of layered frustrations and repression. But it’s such a marvellously constructed, detailed and well observed performance that it feels a masterful piece of art to be admired rather than loved. For all the film centres Archer in the story, he is a hard man to care for or invest in. Pfeiffer gives a wonderful performance as the far freer, intelligent and daring Ellen – but there is a slight lack of spark between them, for all the brilliance of both actors the feeling of an overpowering, obsessive love just doesn’t quite come out of the picture.

This coldness of the construction, carries through every frame. It is perhaps an easier film to admire than love, for all its brilliant construction. It is perhaps too successful in establishing the sharp rules of its society, and does not invest enough time in looking at the raw passions that bubble under the surface of its characters. It never quite explores the inner life of its characters, and they remain slightly distant objects from us. To be fair, this works very well in some cases: Winona Ryder as May carefully plays her hand throughout the film, so that it is a shock in the final scenes where she reveals depths of determination, strength of character and manipulation that far dwarf anything Archer is capable of. Where he is a man with a wistful longing for what he wants, but lacks the will to take it, she knows what she wants and is determined to take it.

The film uses its mostly British cast very well, their understanding of period and these sort of society rules crucial to its success. Margolyes, Wilson and McCowen in particular are very impressive as very different types of society bigwigs. Scorsese’s film contains many other things to admire, but it’s such a wonderfully made piece of film-making, so overburdened with intelligent interpretation of the novel that it fails to make a real emotional connection with the viewer. You will respect and enjoy scenes from it, but perhaps find its running time as overbearing as the characters find the society they are in, and eventually find yourself needing to come up for air.