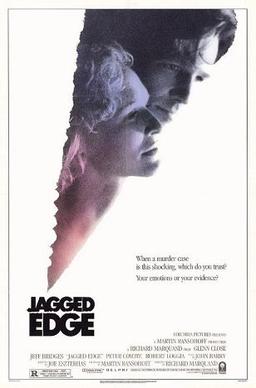

Exploitation and barmy courtroom and steamy romantic couplings abound in this silly but fun mystery

Director: Richard Marquand

Cast: Glenn Close (Teddy Barnes), Jeff Bridges (Jack Forrester), Peter Coyote (DA Thomas Krasny), Robert Loggia (Sam Ransom), John Dehner (Judge Carrigan), Karen Austin (Julie Jenson), Guy Byd (Matthew Barnes), Marshall Colt (Bobby Slade), Louis Giambalvo (Fabrizi), Lance Henricksen (Frank Martin), Leigh Taylor Young (Virginia Howell)

Teddy Barnes (Glenn Close) is done with criminal law after her time at the DA’s office, working under ambitious, unscrupulous Thomas Krasny (Peter Coyote). But she’s dragged back in to defend handsome newspaper editor Jack Forrester (Jeff Bridges), accused of brutally murdering his wife and her maid (for the money naturally). Teddy takes the case and soon crosses that line marked “personally involved” as she and Jack swiftly move from riding horses to riding each other. But what if Jack is really guilty after all?

Jagged Edge is a big, silly courtroom drama, a sort of erotic thriller B-movie that got some serious notice because two critically-acclaimed, three-time Oscar nominated actors fleshed out the cast. Written by Joe Eszterhase (for whom this was the springboard for a career of sex-filled, murder-and-legal dramas that would culminate, via Basic Instinct, with Striptease), Jagged Edge is full of pulpy, super-tough dialogue that its cast loves to chew around their mouths and spit out. It’s got the sort of courtroom dynamics that would see a case thrown out in minutes and would make its lead character unemployable in seconds. It’s daft, dodgy and strangely good fun for all that.

What it is not, really, is either any good or in any way surprising. One look at rugged, casually handsome Jeff Bridges and sharp-suited, charming-but-whipper-smart Glenn Close and you just know its only a matter of time before they end up in bed together. This leads to all sorts of unprofessional sex-capades and legal decisions, not to mention the sort of pathetically readable poker-faces in courtrooms that I would definitely not want from my lawyer.

Jagged Edge makes no secret of its hard-boiled, pulp roots. It opens with a POV home invasion as the killer breaks into his victim’s house that is only barely the right side of exploitative. Marquand doesn’t shirk any opportunities to chuck crime scene photos up on the wall. Peter Coyote’s uber-macho DA loves to say lines like “he has a rap sheet longer than my dick”. Best-in-show Robert Loggia (Oscar-nominated) is the sort of grimy flatfoot investigator who has a fridge full of booze and can’t go more than five words without cussing (when asked if his mother ever washed his mouth out with soap he simply responds “Yeah. Didn’t do no fuckin’ good”).

It’s similarly open about its sexy energy. Close and Bridges have a blue-filtered, late-night roll in the sheets, made even more exciting (perhaps) by the fact she spends half the film suspecting he did the deed. That’s the question the film challenges us with. On the one hand, Bridges seems far too boyish and aw-shucks to have slaughtered two women with a jagged knife. He sure looks upset when he visits the crime scene. Problem is there doesn’t seem to be any other possible suspect, and all that circumstantial evidence just keeps stacking up around him.

Close plays all this with a great deal of force and emotional intelligence, far more than the part (or the film) really deserves. She’s amicably separated from her husband (a very decent guy) and the film even finds a little ahead-of-its time space to make clear that Kransky’s animosity for her (and her loathing of him) is based on his sexual harassment of her as much as his flexibility with courtoom rules. Close balances the whole B-movie set-up with a real dedication – it’s effectively a warm-up (in a way) for the nonsense she’d play in Fatal Attraction.

Bridges is also pretty good, always keeping you guessing from scene-by-scene. How bothered is he when he spreads his wife’s ashes off his yacht? But then how affronted and hurt he looks when he is accused of the crime? It’s a tricky part, but he does a great job of constantly shifting the audience viewpoint and his relationship with Close’s Teddy is just smooth enough to have you guessing how genuine it is.

Wisely – perhaps – he doesn’t hit the stand during the trial. It would probably lead to drama meltdown. The courtroom is full of unbelievable curveballs, witnesses crumbling in a way they never do in real life. Every single disaster for each case is signposted by the fixed horror on the faces of the lawyers. Revelations fly-in and a new suspect effectively incriminates himself mid-trial to the delight of all (this suspect even enforces his caddishness by threatening Teddy in a car park in another moment where the film tries too hard).

The film culminates in the inevitably silly reveal, with plot twists abounding, where we are asked to believe that a killer who has ingeniously considered every single angle of his crime casually leaves incriminating evidence hanging around waiting to be discovered. Its final scene, where the killer is revealed, is either tense or unbearably, ridiculously stupid, depending on your viewpoint (everyone behaves ludicrously out-of-character and takes stupid, unnecessary risks). But for the bulk of its runtime, Jagged Edge is dirty, cheap fun.