Every parent’s nightmare gets tackled in this efficient, smart (but not quite smart enough) thriller from Ron Howard

Director: Ron Howard

Cast: Mel Gibson (Tom Mullen), Rene Russo (Kate Mullen), Gary Sinise (Detective Jimmy Shaker), Delroy Lindo (FBI Special Agent Lonnie Hawkins), Lili Taylor (Maris Conner), Liev Schreiber (Clark Barnes), Donnie Wahlberg (‘Cubby’ Barnes), Evan Handler (Miles Roberts), Brawley Nolte (Sean Mullen), Paul Guilfoyle (FBI Director Stan Wallace), Dan Hedaya (Jackie Brown)

There is no greater fear for any parent than losing a child. Doesn’t matter if you are prince or pauper, the same heart-pounding dread is there. But sometimes the risks are greater if you a prince. Because the more money you have, the more likely a kidnapper might think you’d be willing to swop that money to get your kid back.

It’s what kidnappers decide when they take the son of Airline owner Tom Mullen (Mel Gibson). The kidnappers want $2million and no questions asked, in return for his son Sean (Brawley Nolte). Tom and his wife Kate Mullen (Rene Russo) are willing to pay – with the advice of FBI Agent Lonnie Hawkins (Delroy Lindo). But after the first bungled handover, Tom becomes convinced the kidnappers have no intention of returning his son alive. So, he takes a desperate gamble to try and turn the tables, much to the fury of secretive kidnapper (and police detective) Jimmy Shaker (Gary Sinise).

Ransom is a change of pace for Ron Howard, his first flat-out thriller. And it’s a very good one. Ransom has a compulsive energy to it, powered by sharp filming and cutting and some impressively emotional performances from the leads. It also takes a number of unexpected narrative twists and turns – before it reverts to a more conventional final act – and manages to keep the viewer on their toes.

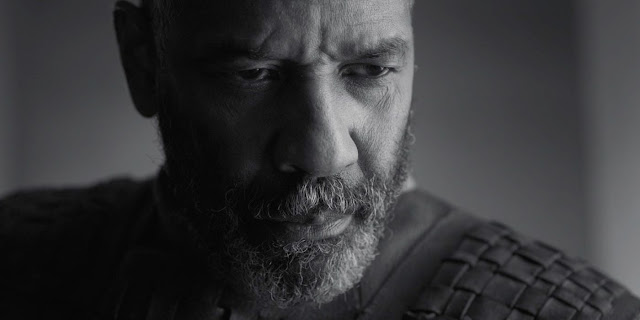

Its main strength is an emotionally committed performance from Mel Gibson. Taking a leaf from Spencer Tracy’s book, this is Gibson at his best, very effectively letting us see him listen and consider everything that happens around him. Mullen is a determined man who plays the odds, and cuts corners only when he must – but is also convinced of his own certainty. He applies his own business learning – of negotiation and corporate deal-making – to this kidnapping, which is an intriguingly unique approach. Gibson’s performance is also raw, unnerved and vulnerable and he plays some scenes with a searing grief you won’t often see in a mainstream movie. Russo does some equally fine work – determined, scared, desperate – and their chemistry is superb.

Howard coaches, as he so often does, wonderful performances from his leads and from the rest of the cast. Gary Sinise turns what could have been a lip-smacking villain into someone chippy, over-confident and struggling with his own insecurities and genuine feelings for his girlfriend (a doe-eyed Lili Taylor, roped into kidnapping). Delroy Lindo is very good as the professional kidnap resolver and there are a host of interesting and engaging performances from Schreiber, Wahlberg, Handler and Hedaya. Ransom turns into a showpiece for some engagingly inventive performances.

Howard also triumphs with his control of the film’s set-pieces. The kidnapping sequence is highly unsettling in its slow build of the parent’s dread. The first attempted exchange is a masterclass in quick-quick-slow tension, with Gibson and Sinise very effective in a series of cryptic phone calls. The ransom phone calls are similarly feasts of good acting and careful cross-cutting, which throb like fight scenes. Howard understands that this is a head-to-head between two men struggling in a game of deadly one-up-manship, both of them constantly trying to figure out not only their next move, but the likely reaction of their opponent.

For much of the first two thirds of the film, Ransom is very effective in its unpredictability. There is a genuine sense of dread for how this might play out and the radical changes of plan both sides of the kidnap play out land events in a very different place than you might expect at the start. The more hero and villain try to out-think each other, the murkier the plot becomes.

It’s unfortunate that the final third devolves into a more traditional goody/baddy standoff with guns, punches and our hero reasserting his control (and the safety of his family) through the fist and the trigger. But then I guess in the 90s you couldn’t have a Gibson film without a bit of action. But when the film focuses on the thinking, talking, slow-burn tension and the sheer terror of parents who have lost a child, it’s a very effective and tense film that stands up to repeat viewings.