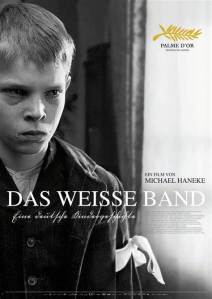

Haneke’s fascinating puzzle is a profound and challenging modern masterpiece

Director: Michael Haneke

Cast: Daniel Auteuil (Georges Laurent), Juliette Binoche (Anne Laurent), Maurice Bénichou (Majid), Lester Makedonsky (Pierrot Laurent), Walid Afkir (Majid’s son), Annie Girardot (Georges’s mother), Daniel Duval (Pierre), Bernard Le Coq (Georges’s boss), Nathalie Richard (Mathilde)

Is any film more aptly named than Caché? Haneke’s film keeps its cards so close to its chest, it’s entirely possible revelations remain hidden within it in plain sight. Caché famously ends with a final shot where a possibly crucial meeting between two people we’ve no reason to suspect know each other plays out in the frame so subtly many viewers miss it. It shows how Haneke’s work rewards careful, patient viewing (and Caché is partially about the power of watching and being watched), but also how unknowable the past can be. It’s a chilling and engrossing film that fascinates but never fully reveals itself.

Georges Laurent (Daniel Auteuil) lives a life of success. A wealthy background, host of a successful TV literary debate show and living in an affluent suburb of Paris, he’s married to publisher Anne (Juliette Binoche) and father to young champion swimmer Pierrot (Lester Makedonsky). But there’s a serpent in his Garden of Eden. Georges and Anne are plagued by a stream of videos arriving at their house. These show long, static shots of their home and are accompanied by crude, graphic drawings. Someone is watching their house and the dread that this could escalate at any time is consuming them. But does Georges know more – do the messages chime with guilty memories in his past?

Haneke’s film is a multi-layered masterpiece, a haunting exploration (free of clear answers) into the things we prefer to forget, the hidden horrors we supress. It’s a film all about the shame and guilt buried amongst the everyday. Haneke even shoots the film on hi-definition video so that the surveillance footage of Georges and his home visually merges with the ‘real’ images of the couple. Within that, Caché starts to unpack the hinterland we hold as individuals (and, quite possibly as entire nations) of the guilts of our past that keep bubbling to the surface to bite us.

Caché is shot through with Haneke’s genius for menace and veiled threat. Can you imagine anything creepier than a camera set up outside your home, filming everything you do – but never knowing where it is? It’s an invasion of privacy that is insidious and covered in the additional menace that, at any time, it could escalate to something worse. The creeping, invasive tyranny of surveillance is in every inch of Caché, its omnipresence giving every interaction the feeling of being watched (something Haneke plays up – watch a man watching Anne when she sits in a café with a friend).

So gradually the book-lined world of the Laurents becomes a base under siege, a feeling amplified by Haneke’s mix of smooth camera movements adrift from establishing shots: constantly the camera glides through a space where we feel we neither truly understand the geography or are confident about the time. It’s accentuated by the window-free room the Laurents largely inhabit. In fact, their whole home feels window free, with curtains frequently drawn and rooms plunged into darkness, the family throwing up a shield to protect them from the outside world.

Or is it to cut them off from the unpleasant facts of life? It becomes clear Georges has built a world around himself, where he is the hero and all traces of the unpleasant or disreputable in his past have been dismissed to the dark recesses of memory, never to be accessed. Played with a bull-headed arrogance by Daniel Auteuil, under his assurance Georges is prickly and accusatory, liable to lash out verbally (and perhaps physically, considering the threat he carries in two key scenes). Auteuil masters in the little moments of startled panic and stress that cross Georges’ face, a man so used to a world that matches his needs, that anything questioning that is met with rejection.

It’s why he lies to Anne about his growing suspicions about the source of the tapes. The cartoons hint at a series of (deeply shameful) interactions, when he was a child in the 60s, with a young Algerian boy, Majid, who his parents considered adopting after the death of Majid’s parents. It was Georges lies that forced this boy out of his perfect farm-house into the cold-arms of the unfeeling French orphanage system. This is the original sin of Georges’ life, arguably the foundation of his success – a guilty secret that so haunts and disgusts him, even the slightest mention of it brings out the muscular aggression he otherwise keeps below the surface.

Of course, it’s hard not to see an echo of France’s colonial past. One of the things that works so well with Caché, is that this subtext is there without Haneke ever stressing it. Just as Georges’ lies forced Majid into a life of depression and misery, so France’s treatment of Algeria is the terrible shame the nation would rather forget. Majid’s parents died in a famously brutal stamping out of an Algerian protest in Paris in October 1961 (the deaths of over 200 people at the hands of French government forces only came to light decades later). The anger many show when presented with inconvenient, horrible past deeds (both personal and national), only feels more relevant today with our culture battles over history.

Georges sees himself as a victim of a vicious campaign. But, when Georges meets Majid, played with startling vulnerability by Maurice Bénichou, he seems light years away from the sort of man who could possibly be capable of such a campaign. Indeed, when a video of Georges encounter with Majid is widely shared, it is Georges (as even he admits) who appears the bully and aggressor. Majid has been demonised in Georges’ memory – in his nightmare he becomes an axe-wielding monster-child – but he’s an innocent, who had everything taken from him in a micro-colonialist coup carried out by a 6-year-old Georges. A coup the adult Georges has let himself forget, making him little different from France itself. (We are reminded the cycle continues, with constant background news footage of Iraq, ignored by the Laurents.)

The mistakes repeat themselves, but they don’t trouble the complacent middle-classes who benefit from them. Georges will even use his influence to have Majid and his son bundled into a police van. Of course it leads to an outburst that will shake this world up. Haneke’s films have always been realistic when it comes to the visceral horror of violence, and Caché contains an act of such shocking violence that it will leave the viewer as speechless and distressed as the witnesses.

And still the question hangs: who? It could be anyone. At one-point Georges storms out of his front door to confront the mystery video-sender, only to return to find a video wedged in the door. It’s literally impossible for this video to be placed without him seeing it done. Haneke is so uninterested in the whodunnit part that, perhaps, he’s implying the perpetrator is the director himself, using the mechanics of film-making to entrap the guilty parties. It fits with the coldly intellectual steel-trap part of Haneke’s mind, the part that uses films (like Funny Games) to tell off and preach. What other director would be more likely to set himself up as unseen antagonist in the film?

And does Georges learn anything? He will continue to confront characters who challenge his world view and dispatch (like nations) his guilt to the recesses of memory. His begrudging peace with his wife – a superbly restrained Juliette Binoche, increasingly resentful at her husband’s secrets – seems built on the shaky ground of their continuing mutual comfort. And suspicions linger over his son, an increasingly hostile figure who (just perhaps) is learning more about the flaws of his parents than they would be comfortable with.

Of course, this might all be open to interpretation from multiple angles. After all the film is called Caché. Haneke has hidden enough subtle implications in it that it can reward analysis from multiple angles. Shot with his characteristic discipline that suggests a dark, creeping fear behind every corner, it’s a masterclass in suggestion and paranoia. Brilliantly unsettling and constantly reworking itself before your eyes, it’s a masterpiece.