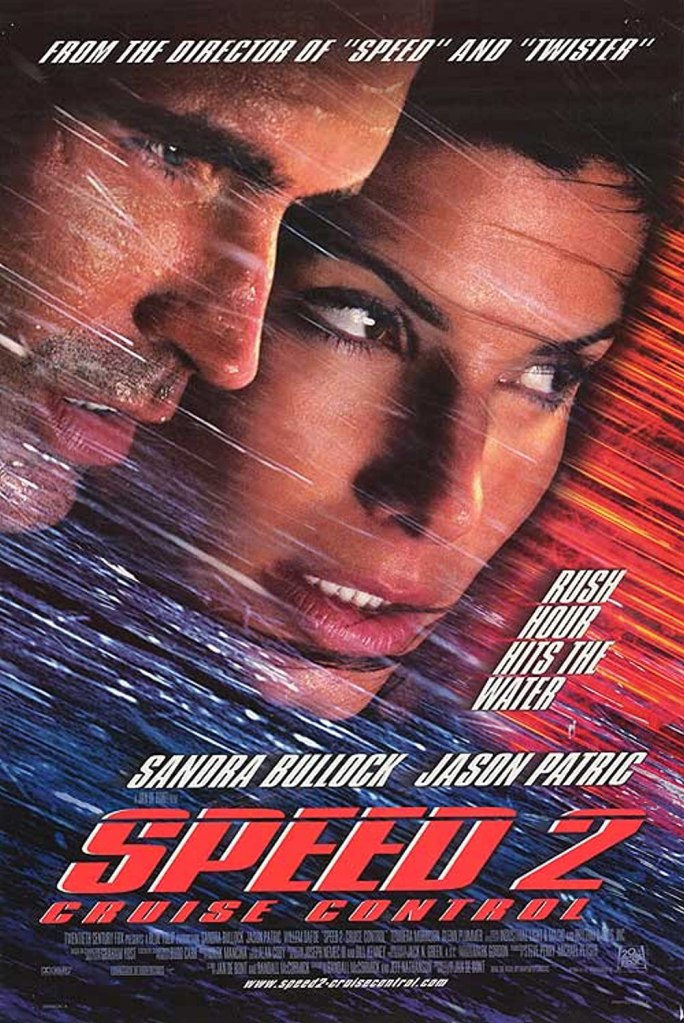

It seemed like such a good idea at the time… Keanu Reeves wisely passed on Speed 2 – so should you

Director: Jan de Bont

Cast: Sandra Bullock (Annie Porter), Jason Patric (Alex Shaw), Willem Dafoe (John Geiger), Temuera Morrison (Officer Juliano), Glenn Plummer (Maurice), Brian McCardie (Merced), Christine Firkins (Drew), Mike Hagerty (Harvey), Colleen Camp (Debbie), Lois Chiles (Celeste), Royale Watkins (Dante)

In 1996 Keanu Reeves turned down a huge salary for Speed 2. Everyone in Hollywood thought he was mad. On June 13th 1997, Speed 2 was released. On June 14th everyone thought Keanu Reeves was a genius. It’s quite something when one of your best ever career moves was not doing a movie. But God almighty Keanu was right: time has not been kind to Speed 2 – and even when it was released it was hailed as one of the worst sequels ever made. It’s like de Bont and co sold their souls for Speed and in 1997 the Devil came to collect.

Keanu’s Jack Traven is clumsily replaced by Jason Patric’s Alex Shaw – although the dialogue has clearly only had the mildest tweak as Shaw has inherited Traven’s job, friends, personality and girlfriend Annie (Sandra Bullock – elevated to top billing but even more of a damsel-in-distress than in the original). Alex and Annie are wrestling with making a long-term commitment – see what I mean about this script only be mildly tweaked? – when they decide to take an all-or-nothing cruise. Shame the cruise liner is hijacked by deranged computer programmer turned bomber Geiger (Willem Dafoe). With the boat powering through the water towards a collision on shore, can Alex save the day?

You’ve probably noticed the disparity between the title Speed and the setting: a slow-moving cruise liner. At one point, Alex asks how long it would take an oil tanker to move out of a collision course with the liner – “At least half hour – that’s not enough time!” he’s told. The very fact that a debate whether 30 minutes will be enough time in a flipping film about speed shows how far this sequel has fallen. How did anyone not notice this?

Pace is missing from the whole thing. The script is truly dreadful. Paper-thin characters populate the cruise liner, none of whom make even the slightest impression. At one point a character breaks an arm and then immediately shrugs off the injury to steer the ship. The script is crammed with deeply, desperately unfunny “comedy” beats. Bullock’s character seems to have transformed into a ditzy rom-com wisecracker – with a “hilarious” running joke that she’s a terrible driver (geddit!??!) – and, instead of the charming pluck she showed in the first film, is now an irritating egotist. She still fares better than poor Patric, who completely lacks the movie star charisma of Reeves and utterly fails to find anything that doesn’t feel like a low-rent McClane rip-off in his character.

It’s like de Bont forgot everything he knew about directing in the three years between the two films. If anything, this feels like a well below average effort from a novice director. The humour is dialled up with feeble sight gags and the film takes a turgid 45 minutes to really get going (most of which is given over to derivative romantic will-they-commit banter between Patric and Bullock).

de Bont basically flunks everything. He fails the basic directing test of confined-spaces thrillers like this by never making the geography clear to the viewer. I challenge anyone to really understand how characters get from A to C on this boat. The long introductions are supposed to establish these basics (see Die Hard for a masterclass in this), but here you haven’t got a clue about what’s where or why some locations are more risky than others. There is a spectacular lack of tension about the whole thing – it’s not really clear what Dafeo’s lip-smacking, giggling, leech-using (yes seriously) villain actually wants or how his scheme works, and the momentum of the boat towards unspecified destruction is (a) hard to see on the open water with no fixed point to compare the speed with and (b) even when we get that, not exactly adrenalin fuelled anyway.

de Bont’s comedic approach to much of the material might have worked if he had any sense of wit or comic timing in his direction. Or if Patric had been more comfortable with the wit the part requires. Bullock instead feels like she has to joke for all three of them, to disastrous effect. There are a couple of semi-comic sidekicks sprinkled among the supporting players, but none of them raises so much as a grin. The film can’t resist implausible in-jokes, like bringing back Glenn Plummer’s luckless character to have his boat swiped by Alex (they even leave in a mildly altered “what are you doing here?” line, as if they didn’t realise until shooting it that Keanu wasn’t going to be there).

It ends with a loud crash of a boat into the shore which cost tens of millions of dollars (at the time one of the most costly stunts ever) but just looks like a fake boat ripping through a load of backlot buildings. It’s a big, loud, dull, slow ending to a film that looks like it was made by people who had no idea what they were doing but enough power to ignore anyone who might have been able to point out what they were doing wrong. Speed 2 remains the worst sequel ever. Reeves went off to make The Matrix. Who’s the idiot?