Tolstoy is boiled down in this epic and luscious but soapy adaptation of the greatest novel ever

Director: King Vidor

Cast: Audrey Hepburn (Natasha Rostova), Henry Fonda (Pierre Bezukhov), Mel Ferrer (Andrei Bolkonsky), Vittorio Gassman (Anatole Kuragin), Herbert Lom (Napoleon Bonaparte), Oskar Homolka (Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov), John Mills (Platanov), Anita Ekberg (Hélène Kuragina), Helmut Dantine (Fedor Dolokhov), Tulio Carminati (Vasily Kuragin), Barry Jones (Mikhail Rostov), Milly Vitale (Lisa Bolkonskaya), Lea Seidl (Natalya Rostova), Anna Maria Ferrero (Mary Bolkonskaya), Wilfrid Lawson (Nikolai Bolkonsky), May Britt (Sonya Rostova), Jeremy Brett (Nicholas Rostov)

Let’s just say it right from the start: you can’t do Tolstoy’s War and Peace in three hours. All you can hope for is the little chunk of it you’ve bitten on is the most succulent part. King Vidor’s War and Peace zeroes in on the elements of the book Hollywood is most comfortably reproducing: a golden-tinged romance between Natasha and Pierre and the sweeping epic spectacle of Napoleon’s soldiers surging towards Moscow and limping home in the snow. While War and Peace, bravely, barely cuts a single major character or development, almost every other theme Tolstoy attempted gets shoved to the margins. This makes it both a SparkNotes version of the Greatest-Novel-Written, but also a very earnest attempt to do the impossible.

Tolstoy’s story stretched over seven years. The great Russian struggle against Napoleon is a backdrop to the lives of dilettante-turned-thinker Pierre Bezukhov (Henry Fonda), vivacious and impulsive Natasha Rostov (Audrey Hepburn) and stolid-but-thoughtful Andrei Bolkonsky (Mel Ferrer). Around them swirl other characters: Natasha’s warm-but-useless family, worthless womaniser Kuragin (Vittorio Gassman), his sister and Pierre’s faithless wife Hélène (Anita Ekberg), heartless roister Dolokhov (Helmut Dantine) and of course Napoleon (Herbert Lom) and his military antagonist, the pragmatic Kutuzov (Oscar Homoloka). Natasha falls in love with Andrei, betrays him then finds maturity caring for soldiers retreating from Napoleon, all while silently loved by Pierre.

This is compressed together into a film that certainly doesn’t feel like it is covering seven years despite its epic run-time. No one seems to age (just as well since everyone starts the film far too old) and the attempt to cover as much of the plot as possible means the film is moving forward so swiftly any sense of time is lost. It also means that the script frequently has to fill in the dots, communicating vital information that alters the lives of characters – major figures often die or are married off in short, easy-to-miss, sentences – and the ideas Tolstoy masterfully expounded about spirituality, destiny, fate, the quest for a life of meaning, are pretty much rinsed out in the plot focus.

War and Peace effectively reduces Tolstoy down into a sudsy romance against an epic backdrop. The romance is handled reasonably well, even if there is very little chemistry of any sort between any of the three protagnonists. Tolstoy’s rich leads, with the fascinating inner lives, are reduced to pen-portraits. There are odd moments where we have access to the inner thoughts and voices – sprinklings of voiceover dot around the picture – but they never feel real. Andrei has been robbed of the decency and warmth behind his thoughtfulness that attracts Natasha, while Pierre feels more like a second father or benevolent uncle than a soul mate.

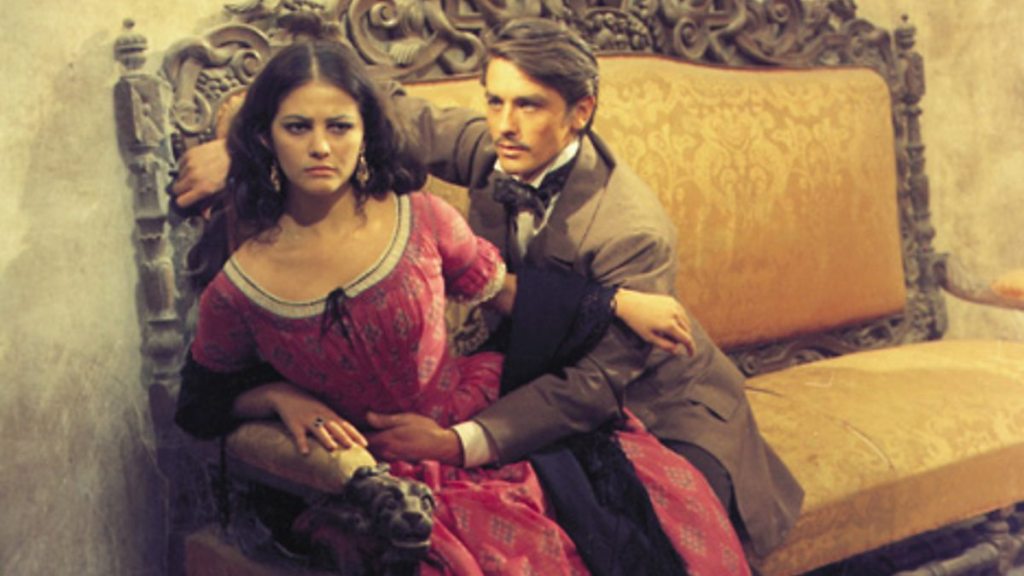

This stripping down of Tolstoy’s complex characters to their bare principles fatally compromises all three lead performances. Hepburn comes off best, making a decent fist of Natasha Rostov. This is, after all, a character who embodies in her mix of passion, loyalty, fecklessness and self-sacrifice the very nature of Russia itself. No adaptation has ever managed to translate Tolstoy’s unplayable creation, but Hepburn has all the radiance and self-sacrificial guilt down pat. The film has to rush through her foiled elopement with Kuragin (Hepburn has more chemistry with Gassman than any of the others and their near elopement is artfully framed by Vidor with mirrors, reflections and a real illicit charge). Hepburn conveys the mesmeric impact this playboy has on Natasha and her selfish, tear-stained fury at the foiling of her disgraceful plans is laced with enough genuine guilt and pain by Hepburn to keep us caring. Hepburn skilfully translates this into a far wiser and more generous Natasha, placing others needs before her own.

By contrast, literally nobody reading the novel could picture Henry Fonda as Pierre (he’s the wrong age, shape, manner – there is nothing right about him at all), but Fonda does his best (as one reviewer at the time mentioned he’s one of the few actors who looks like he has read the book). He never convinces as the drunken playboy who gets into duels (he looks and sounds far too mature) and similarly doesn’t capture any of Pierre’s doubt and uncertainty (Fonda always looks like he knows exactly what he needs to do). It’s an intelligent reading for all that, but fundamentally miscast. Which is more than you can say about Mel Ferrer who turns Andrei into a stuff bore, ramrod straight and flatly monotone, an intellectual we never get interested in.

Honestly the film would have done better cutting more. Fonda is so unconvincing as the reckless young Pierre, they may as well have made him officially middle-aged to begin with. Similarly, Natasha’s brother Nicholas and his one-sided romance with cousin Sonya is given a mention so token its likely to confuse casual viewers. Andrei’s first marriage gets about five minutes and his sister Mary is reduced to a few dull scenes. Even John Mills’ thoughtful performance as Platanov strips out the characters worldview (and its profound impact on Pierre), turning it into one of simple, symbolic tragedy. It’s all the more noticeable when the film gets some stuff right, most notably Helmut Dantine’s bullying Dolokhov who war turns into someone with a sense of shame.

Faring much better are the historical characters. Like all War and Peace adaptations, this dials up the presence of Napoleon played with an excellent puffed-up grandeur by Herbert Lom, prowling with a swagger stick and collapsing into childish frustration, then silent tears as his plans for world domination collapse. Equally stand-out is Oscar Homoloka as scruffy realist Kutuzov.

Vidor’s film may offer a simplified, romantic vision of the characters but he delivers on the scale. If you can bemoan the fact the peace leaves the characters neutered, the film completely nails the war. War and Peace is a beautifully filmed by Jack Cardiff. From the sweeping vistas of the battlefield of Borodino, to the Dante-tinged flames at Moscow that cast orange light through the arches of a monastery where the Rostov’s take shelter, through the white-and-blue chill of the snow-covered retreat from Moscow, the film is an explosion of gorgeous colours. It’s also got the scale that old Hollywood loved. Borodino is restaged seemingly at 1:1 scale with a literal army of extras, soldiers and cavalry charging in their hundreds in long-shot and cannon fire peppering the land as far as the eye can see. Ballrooms are overflowing with extravagantly costumed extras and seemingly never-ending lines of Frenchmen march through the snow in the films closing moments.

It’s what this War and Peace is: a coffee-table accompaniment to the novel. You can look at the images it brings to life and the sweeping camera work Vidor uses to create nineteenth century Russia. But you’ll not understand anything that makes the novel great. In fact, to the uninitiated, you are likely to come away thinking the film must be a sort of high-brow Mills-and-Boon page-turner, a Gone with the Snow. What this tells us, more than anything, is that fifteen years on from the definitive Hollywood epic, Hollywood was still trying to remake it – and bringing Tolstoy to the screen was very much second to that.