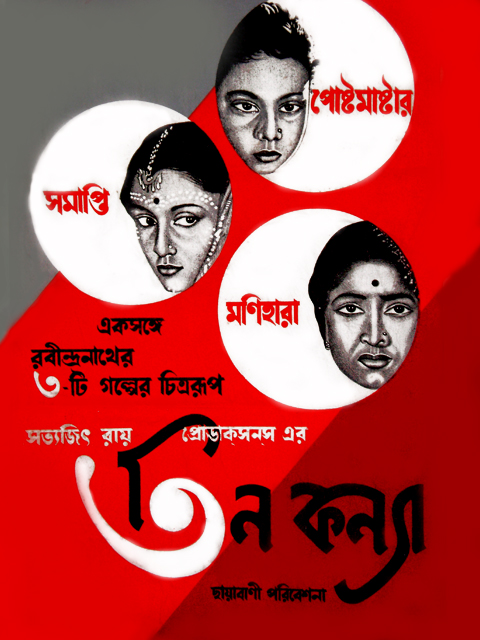

Satyajit Ray’s trilogy comes to close with another masterfully done small-scale story of hope and loss

Director: Satyajit Ray

Cast: Soumitra Chatterjee (Apu), Sharmila Tagore (Aparna), Alok Chakraborty (Kajal), Swapan Mukherjee (Pulu), Dhiresh Majumdar (Sasinarayan), Sefalika Devi (Sasinarayan’s wife), Dhiren Ghosh (Landlord), Tusar Banerjee (Bridegroom), Abhijit Chatterjee (Murari)

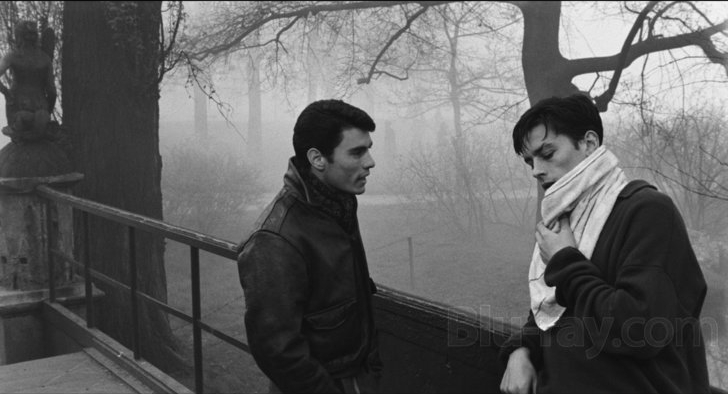

As he stands, consumed with despair, watching a train rush perilously close to him, does Apu (Soumitra Chatterjee) remember when he ran with excitement after the trains as a boy? Apu Sansar, the conclusion of Ray’s breathtakingly humanist trilogy, concludes another cycle in Apu’s life; one touched, as with the previous ones, with loss, tragedy and a dream of hope. Beautifully filmed, simple but deeply affecting, it’s a breath-taking culmination of this masterful trilogy.

Apu (Soumitra Chatterjee) is now a young man longing for a career as a writer in Calcutta. Attending the marriage of his friend Pulu’s (Swapan Mukherjee) cousin Aparna (Sharmila Tagore), he finds himself surprisingly roped into the role of groom to take the place of the unsuitable intended (as part of Hindu tradition to prevent the risk of Aparna never marrying). Returning with Aparna to Calcutta – and a life of poverty she is unused to – their romance flourishes into a happy marriage, until tragedy strikes leading to Apu tumbling into years of drift and depression.

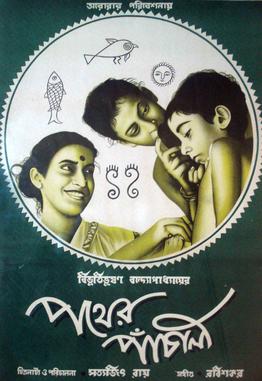

Apu should be used to tragedy by this point. In Ray’s series, death has always raised its deadly force in his life. In Pather Panchali his beloved sister passed away from sudden illness. In Aparajito the death of his mother leaves Apu stricken with guilt and grief. It’s natural that Ray’s subtle trilogy continues to look at how closely tragedy and sadness dog hope and contentment. Tragedy this time strikes Apu out of the blue, a searing, raw pain that Ray conveys to us almost entirely through a series of still, tender shots of Soumitra Chatterjee’s face as Apu’s world falls apart around him.

Ray’s film, with its beautiful observational style and low-key camera work (and use, at several points, of low angles) reminded me sharply on this viewing of Yasujirō Ozu. Apu Sansar follows in Ozu’s footsteps in its careful, focused study of the lives of ordinary people and how whole worlds of love, hurt and joy can be contained within small rooms. Unlike Pather Panchali or Aparajito, there are few shots of the widening countryside or the scale of the cities. Instead, Apu’s world seems smaller and more intimate, its focus on his apartment and a few other locations, site of momentous events that will shape his life.

Marriage is at the heart of that. His relationship with Aparna has an inauspicious start, Apu roped in as a husband due to the mental incapacity of Aparna’s intended. (There are hints that the possibility of a replacement husband being expected lie behind the last minute, out-of-the-blue invite Apu receives from his friend Pulu which, if true, does add a slightly more manipulative quality to his amiable college friend). The two of them don’t know each other and have little or no idea if they even have anything in common. Their first night together is one of slightly awkward, exploratory talking and it leaves the viewer wondering if common ground can be found.

But Ray sketches out the development of this relationship into something strong, living and (eventually) heartbreaking with a mastery of little touches and his skill with montage and transition. Aparna is at first thrown by the poverty of Apu’s life in Calcutta (similarly to the Dickensian nature of Aparajito he lives in a rain-soaked apartment on a month-to-month basis). But she sets to work to turn this place into a home and soon little touches abound that denote their growing closeness. A cigarette pack hidden under Apu’s bed that Aparna has written a message in, pleading him to smoke only after meals. Late night conversations – which involve a brilliant Ray cut as the camera zooms into the fan between them and out again as a transition finds them sitting again opposite each other on a different night. The pleasure Apu takes in buying her the smallest gifts and the pride Aparna has in turning his home into something cleaner and more decent.

The future seems bright for them. In Ray’s trilogy the future and the march of time and civilisation has often been represented by trains. This theme continues masterfully in Apu Sansar, however this time with the train taking on a more sinister, dangerous presence. Apu’s apartment overlooks a major railway junction his home frequently invaded by the sounds of the train and an onslaught of smoke from the engines. Rather than offering tempting possibilities, this increasingly feels like an intrusion, an outside force intruding into the haven that Apu and Aparna are trying to create.

This sense of invasive menace is captured exquisitely in a beautiful but haunting shot as Apu stands on his balcony – the train sounds build and then smoke from the engines pours across the balcony and seems to envelop Apu. His home can be a place of wonder and beauty, but its harmony is always under siege from transportation that, like time, relentlessly moves forwards. It’s the train that will carry Aparna away from Apu, back into the countryside for her fateful lying in before giving birth. It’s a gift of a toy train – a chance at a future together – that Apu’s son will throw in his face five years later. It’s the same train, that dangerous future finally left behind, that Aparna’s father will clutch to him as Apu heads into a more hopeful future. Throughout trains intrude, threaten and signal danger and separation for Apu.

Soumitra Chatterjee is excellent as this young man who has seen so much, learned so many things, but also seems destined to repeat the mistakes of the past. Like his father he is a dreamer, planning a loosely autobiographical novel and beginning to exhibit the same Micawber-like expectations that something will turn-up. Perhaps over time, without tragedy, Aparna might have become his mother, beaten down with the burdens of being the sensible rock for a flighty man unable to settle.

Perhaps tragedy is what is needed for Apu – Apu Sansar is notable for its lack of romanticism for poetic longings and its favouring of embracing actual responsibilities. There are few other films where the destruction of a nascent novel could be met with such bitter-sweet acceptance. Certainly, no Western films, where the dream of having it all is baked in. The Apu Trilogy is partially about accepting things as they are and taking on your responsibilities: dreams and self-focused desires have no place in that. After all the trilogies hero, perhaps even more so than Apu, is his mother Sabarjaya who gave everything to give Apu opportunities.

Apu finally accepts his place in this cycle after years of denial and grief by seeking to build a relationship with a son he has never met. Ray charts this slow thawing between strangers with a delicacy and emotional force striking in its simplicity. It’s really striking to me how each film in this trilogy is slightly shorter than the one before, as Ray mastered that less really can be more with every frame: that sometimes the emotional force of a single glance can be greater than that of a tracking shot. Apu Sansar is a film brimming with confidence, from a director who has mastered his aim and subject. A heart-breaking, but also heart-warming, conclusion to a great trilogy.