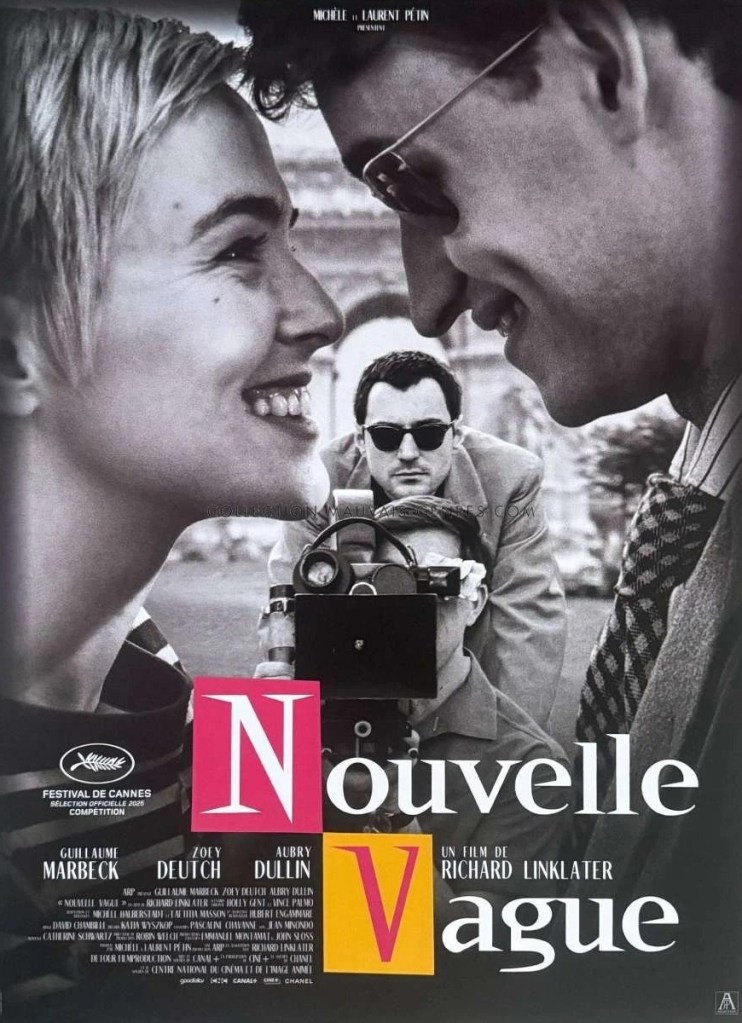

Endearing, hugely enjoyable, vibrant look at the French New Wave which almost feels like a documentary

Director: Richard Linklater

Cast: Guillaume Marbeck (Jean-Luc Godard), Zoey Deutch (Jean Seberg), Aubry Dullin (Jean-Paul Belmondo), Bruno Dreyfürst (Georges de Beauregard), Benjamin Clery (Pierre Rissient), Matthieu Penchinat (Raoul Coutard), Pauline Belle (Suzon Faye), Blaise Pettebone (Marc Pierret), Benoît Bouthors (Claude Beausoleil), Paolo Luka Noé (François Moreuil), Adrien Rouyard (François Truffaut), Jade Phan-Gia (Phuong Maittret)

If ever a film was made for film lovers, it might just be Nouvelle Vague. It’s certainly made by film lovers. You can feel Richard Linklater’s adoration for French New Wave cinema drip off the screen. Nouvelle Vague covers the making of A bout de Souffle in such lovingly researched depth and detail it effectively serves as a sort of making-of-film that was never made. The recreation of the time and era and sequences of the film is absolutely spot on. If you’ve ever watched A Bout des Souffle, you will find something here to delight you and make you want to rush out and watch it once again.

Of course, if you are not immersed (or at least vaguely familiar) with the workings of the burst of creativity that sprang from Cahiers de Cinema in the late 1950s and gave fresh life to an entire generation of French filmmaking, then Nouvelle Vague might be a bit impenetrable. For those not in the know, a host of film-loving French writers (all of whom dreamed of making films) created a monthly magazine awash with fascinatingly in-depth filmic analysis, reclaiming directors like Hitchcock, Welles and Ford as major artists and treating cinema as a serious art form.

Its natural then, that Nouvelle Vague is in love with the art of film-making and the often confused and meandering path a film takes to reach the screen. Few could be more meandering than Jean-Luc Godard (brilliantly recreated, in all his studied cool and casual intellectualism, by Guillaume Marbeck), whose style on A Bout de Souffle was to provide the barest shape of each scene and try to capture reality and truth – to see its lead actors, Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) and American star Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch) react naturally and in the moment in a host of real-life locations.

Nouvelle Vague dives into this with huge enthusiasm and manages to wear its history lesson nature lightly. That’s because Linklater’s film is spy and nimble enough not to wear us down with facts and potted biographies: the dialogue is refreshingly free of people summarising each other’s careers and inspirations. Perhaps Linklater worked out that the film buffs watching – and God, that’s surely most of the audience – are going to know who Truffaut, Rossellini, Bresson, Chabrol, Varda, Resnais et al are already and any newbies can work it out from context. He finds a neat middle ground with each character – and Nouvelle Vague works in practically a who’s-who of French filmic landmark contributors into its slim 90-minute run-time – introduced with a shot of them starring at the camera, their names appearing in caption beneath them.

This tees Linklater up nicely for a wonderful companion piece to Me and Orson Welles: an engrossing look at how a landmark piece of narrative art is created. Nouvelle Vague might have the edge though, because it doesn’t need to introduce any fiction to the story. Instead in its tight focus on the twenty-day shooting schedule for Godard’s first film (shot on the cheap, from a script by friend and rival Truffaut) it finds there is more than enough drama to be had from showing us how making the film went down.

These tensions largely revolve around Godard himself, whose unconventional, vibes-based directing style (he’s as likely to spent a day playing pinball as actually organising a shot) rubs up against his producer de Beauregard (Bruno Dreyfürst), rightly irritated at waste of time and money, while his improvisatory style irritates Jean Seberg (a pitch perfect embodiment by Zoey Deutsch), who wants a clearer script and story. What she doesn’t want is Godard providing her gnomic, cryptic direction, off-camera, between every line she invents in the moment (working to notes, scribbled by Godard that morning), however much she respects Godard’s freshness and spontaneity.

But the most delightful thing about Nouvelle Vague is that, despite the gripes, disagreements and arguments over an intense period of collaboration, it’s also soaked in the love and excitement that comes out of a joint creative endeavour. There are many moments of satisfied, mutual excitement and satisfaction at a job well-done in Nouvelle Vague, and a gloriously warm sense of the respect and support in the French film industry at the time. Linklater’s film is charming, warm and funny when it simply stops and lets us spend time hanging with these people, making a movie that they have a good feeling about (and that we know will become a landmark).

It’s matched by the breathtaking, recreative detail that unpacks how several scenes were captured on camera (they seem to have located every original location!). Godard’s decision to record no sound on set meant the film could be recorded by a shaky, but light, camera that could bob and weave among unknowing Parisian extras, following its characters spontaneous reactions. It’s huge fun to watch Godard sit his cameraman in a wheeled box (to hide him) or see Belmondo (his back to the camera) shout smilingly at passers-by that they are just recording a movie. Linklater lovingly captures how the freshness of scenes, such as Belmondo and Seberg lying in a bedsit, riffing on Bogart films, came about.

Linklater also doesn’t overplay the success of the film – its release and impact is largely told in a few closing captions – and it doesn’t shirk on showing that, for all his genius, Godard could be a difficult and self-important man. Several Godard epigrams are worked into the dialogue, enough for you either to be wowed by his intellect or roll your eyes at his pretension (according to your taste). Instead, he allows the film to focus on the cathartic joy from artistic creation, the camera capturing moments of genuine novelty that would become part of cinematic history in their freshness and vibrancy.

It makes for a genuinely very enjoyable film, with enough energy and joy in it to appeal even to those who have never heard of Godard. And, I must confess, I got another slight jolt of comedy from it by reflecting that if he had ever seen this film, Godard would probably have thought it was nostalgic, soft-soap rubbish.