Brilliant exploration of the Faust story, a superb portrait of a man who sells what passes for his soul

Director: István Szabó

Cast: Klaus Maria Brandauer (Hendrik Hoefgen), Krystyna Janda (Barbara Bruckner), Ildikó Bánsági (Nicoletta von Niebuhr), Rolf Hoppe (The General), György Cserhalmi (Hans Miklas), Karin Boyd (Juliette Martens), Péter Andorai (Otto Ulrichs), Christine Harbort (Lotte Lindenthal), Martin Hellberg (Professor Reinhardt), Tamás Major (Oskar Kroge), Ildikó Kishonti (Dora Martin)

Dictatorships are also times of opportunity for those who can seize their chance. You just need the willingness to craft yourself into exactly what those in power want, learning your lines and putting on the ultimate show of unwavering commitment and devotion. In other words, helps to be an actor. Mephisto is a brilliant portrait of an actor in 1930s Germany who climbs to immense success by playing Mephistopheles on stage while playing Faust in real life, selling his soul for glory.

Hendrik Hoefgen (Klaus Maria Brandauer) is a fiercely ambitious actor, willing to adapt his views and opinions to match whatever the prevailing mood. As he tries to make his name, he throws himself into the Marxist theatre views of his colleagues, scorning the right-wingers among them. He marries Barbara (Krystyna Janda) the stage designer daughter of a liberal Mann-ish author and looks set to become the leading light of left-wing theatre. But that changes when Hitler comes to power and Hoefgen heads for Berlin and the patronage of the powerful Reichs General (Rolf Hoppe), transforming himself into the ultimate ambassador of the Reich’s vision of art.

Mephisto is not only a superbly well-judged film about the dangerous dance between art and politics, its also a brilliant character study of a man with almost no real personality at all. Superbly directed by Szabó (his masterpiece) it’s shot on a rich scale, dripping with the quiet menace of a deadly regime that cares nothing for anyone. All of which only briefly intrudes itself into the self-justifying mind of a man who becomes its willing propaganda mouthpiece, while constantly reassuring himself he’s only an actor.

The beating heart of Mephisto is the astonishing turn from Klaus Maria Brandauer, one of the greatest tour de force performances of the decade. Brandauer’s energy and surface charm is hypnotic. He throws himself into the theatricality, on and off stage, of Hoefgen as well as his boundless enthusiasm. Hoefgen will dance himself to exhaustion to entertain his lover or build grand theatrical castles in the sky with a flurried burst of exuberant passion. But he’s just as likely to erupt in carpet-chewing outbursts of childish rage at actors who don’t match his standards or roles denied him.

In those temper tantrums, you see the child in him. There is something very vulnerable and boyish in Brandauer: his lover, the cynical Black actor Juliette (a superbly whipper-sharp and perceptive Karin Boyd) comments he has the eyes of a child, and you can see that in his understanding of the world. He has a superb ability to divorce himself for the impact of his actions, absorbed entirely in his own theatrical concerns. To Hoefgen, whether or not he plays the lead in Faust or a Moliere farce really is the most important thing in the world. As Brandauer makes clear, it’s not that he’s naïve, more that he’s self-centred and myopic enough not to care.

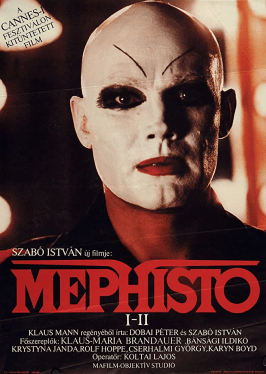

Hoefgen is a man who needs love like oxygen, and he’ll gush it up from the biggest supply he can find. And, frankly, a one-on-one relationship isn’t going to satisfy him. He soaks up audience acclaim – and what we see of his performance as Mephistopheles it’s deserved, it’s a triumph of physicality and insinuating creepiness – but in his private life he oscillates between needy, demanding and distant. He implores his wife Barbara for her love, pawing at her like a teenager and claiming he needs her to save him; then happily leaves her in a heartbeat to seek out new opportunities in Berlin.

His personality seems half-empty. Is he even aware of the homosexual feelings he has for his old friend Otto (a charismatic Péter Andorai), the only person he takes any risks to protect as the head of the National Theatre? Brandauer finds both a childish hero-worship in Hoefgen’s devotion to this left-wing firebrand, and an unspoken romantic yearning (there is a beautiful moment when they stand together at a window and Brandauer rests his head on Andorai’s shoulder like a love-struck puppy). But really Hoefgen is a mass of opinions and views recrafted from the roles he has played (there is a hilarious montage of Brandauer in a parade of different on-stage costumes) and from those around him. He is a blank canvas, ready for the next scene.

Really, he has no principles at all, making him the perfect Nazi actor. Is that what Rolf Hoppe’s General sees in him? The character goes un-named, but Hoppe’s build and manner alerts us to the fact this is Herman Goering. Imposing and terrifying, indulgent of his mistress the mediocre (but now hugely successful) Lotte Lindenthal (a wonderful Christine Harbot, in many ways a female version of Hoefgen), he’s a terrifyingly controlling presence, jovial one moment and irate the next. He also resembles Hoefgen’s Mephisto, making their Faustian pact all the more intriguing. He can give Hoefgen everything he wants, in return for Hoefgen’s absolute devotion and every fragment of his soul. And, of course, Hoefgen gives it without hesitation.

His soul is what changes. Over the course of the regime, he will report or betray fellow actors and turn away friends. Szabó establishes the ruthless vileness of the regime through fellow actor Miklas (György Cserhalmi, very good) who joins the party early, only to become disillusioned at the lack of advancement his mediocre talent gets compared to Hoefgen’s opportunism. His flirtation with Fascism ends in being marched from the theatre by the Gestapo to “die in a car crash” (in cold reality we are shown his fatal shooting, everyone pretends they don’t know he’s been murdered).

Hoefgen recrafts himself into a Fascist ubermensch. His revival as Mephistopheles is praised as “stronger” and more “fierce” than the original. He practices strengthening his handshake after the General points out its limpness. He culminates the film with re-presenting all his compelling “theatre of the people” staging ideas which he’d outlined at the start of the film (for a social realist piece in a working club), into a newly minted Aryan-Hamlet in which he and Lotte play the lead roles.

But it leaves him totally alone. Everyone who sees through his bullshit – from Juliette to his wife Barbara, wonderfully played by Krystyna Janda full of expressive honesty – is betrayed by him. Szabó has Brandauer increasingly turn his self-justifying pleas to the camera, as if we are the only people left listening to him. At the height of his success, Hoefgen becomes more pathetic than ever: frantically collecting socialist flyers from the theatre toilet and burning them in his office and finally terrorised by the General in Nuremberg’s floodlights, the spotlight he’s spent the whole film searching for only confirming to him what a plaything he is to his masters.

Szabó’s film is a brilliant musing on Faust, a wonderfully complex look at how a man can willingly be contorted and changed by ambition. And it demands repeated viewing to appreciate the towering performance by Brandauer, who burns through the screen with a charisma and power that actually heightens our awareness of his character’s blankness behind the show.