Creepy and unsettling horror with a fascinating puzzle-box structure

Director: Zach Cregger

Cast: Julia Garner (Justine Gandy), Josh Brolin (Archer Graff), Alden Ehrenreich (Paul Morgan), Austin Abrams (James), Cary Christopher (Alex Lilly), Toby Huss (Captain Ed Locke), Benedict Wong (Marcus Miller), Amy Madigan (Gladys), Sara Paxton (Erica), Justin Long (Gary), June Diane Raphael (Donna Morgan)

At exactly 2:17am, seventeen young children from the same third-grade class all wake up and run from their houses, their arms trailing behind them like aeroplane wings. The disappearance shatters the local community. Fingers of blame point quickly, most of them at their teacher Justine (Julia Garner). It feels like some bizarre conspiracy, but are there darker forces at play? That mystery will rope in obsessed father Archer (Josh Brolin), troubled cop Paul (Alden Ehrenreich), drug-addict and thief James (Austin Abrams), decent school principle Marcus (Benedict Wong) and the only child from Justine’s class who didn’t disappear, young Alex Lilly (Cary Christopher).

Cregger’s creepy horror movie tells its story from all these character’s perspectives, each section opening like a book’s chapter with their name on the screen. Events re-play from different angles and perspectives and our understanding of events (and their horror!) grows as each person sheds more light on the overall picture. There is a deeply unsettling sense of dread and menace hanging over Weapons, built from the start by an unsettling child narrator who promises us that we are set to see things so unbelievable and ghastly, the authorities covered the whole thing up.

Weapons is influenced by some of the best ensemble dramas – Cregger specifically name-checked Anderson’s Magnolia as an influence – and I also felt it follows very much in the footsteps of Kubrick’s The Shining. It embraces the deeply unsettling dread and horror of quiet menace and the tension of disturbing background events. Which isn’t to say it doesn’t miss out on shattering blood and guts and body horror inspired by Cronenberg and The Thing: when the gore comes in Weapons it’s visceral, gut-wrenching and impossibly bloody.

It taps into everyday fears and horrors then takes them to the nth degree. What parent hasn’t feared the inexplicable disappearance of a child? And when disasters like that happen, people often lash out the suspicious. Poor Justine – a fine performance of outer abrasiveness hiding gentleness and vulnerability by Julia Garner – sticks out like a sore-thumb in this small community. An outsider with a prickly personality and a destructive streak a mile long, a little too fond of vodka (which she buys by the bucketload) and extra-marital sex with married men (which cost her a job at her previous school).

Her stumbling attempts to sympathise with the parents is made worse by the fact she has no clues to offer them. Not helpful (and you can’t help but sympathise with Justine here, as this is a true nightmare set-up) when everyone else is convinced she must know something. Further modern fears are tapped into when Justine faces a campaign of silent intimidation in her home by a faceless persecutor and her car is painted with the word ‘Witch’ (a brilliant little touch making her car instantly recognisable in all the other perspectives that follow).

The loudest voice of this fractured community becomes Archer, played with gruff guilt and fury by James Brolin, pestering the police with his Justine-centred theories and bulldozing other parents for evidence. It’s a dark irony of course that Archer’s paranoid investigations – focused on triangulating a shared route from the direction the children are seen running in doorbell cameras – turns out to be much closer to the truth than the official investigation (but then the police don’t realise they are in a horror movie here, whereas Archer surely starts to think he might be). Similar to Justine, Archer surprises us with his concealed decency and emotional vulnerability, another success in Cregger’s film where greater character depths are constantly revealed.

It works both ways as the more we see of Alden Ehrenreich’s police officer Paul, the less we like him. At first he seems a slightly luckless soul with a gentle heart, but he emerges more and more as a selfish bully who doesn’t think about twice about hurting people around him then worries endlessly about the consequences. Similarly, Austin Abrahm’s drug-addict burglar stumbles far closer to the truth than anyone else – but his interest in it is connected solely to his desire for $50k reward (and it’s hard not to start to think Paul is fairly interested in that as well).

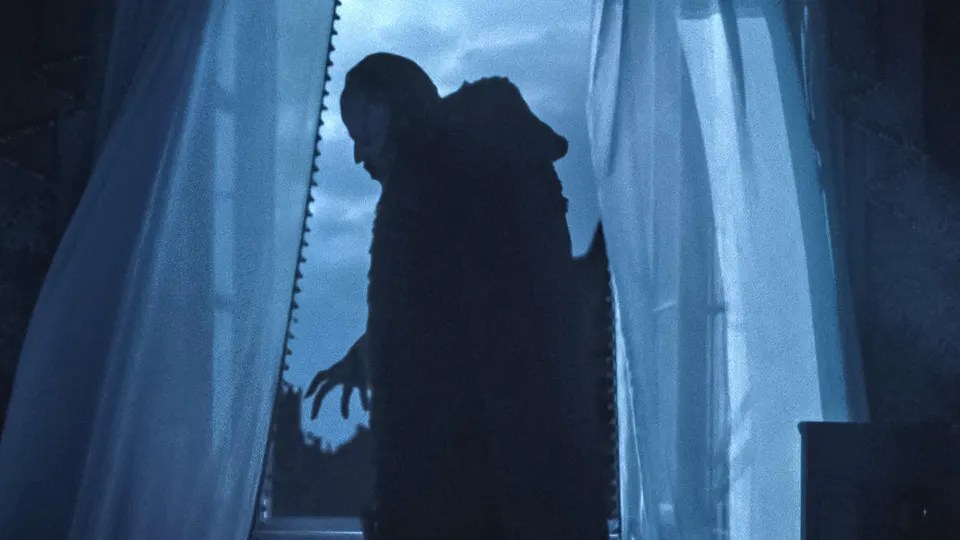

The storyline of these characters unspools in Cregger’s short story structure very effectively, the camera frequently trailing behind each character in a series of tracking shots (this means we often only see the facial reactions when the scene repeats from a different perspective). Cregger’s shies away from jump scares (not that he doesn’t use these quite effectively at several points) in favour of simple shots and draining out sounds to let quiet background moments create dread. Perhaps most chilling of all sees a character sleeping in a car being slowly approached by a mysterious woman, a scene of such sustained but simple tension it will have you twitching in your seat.

To reveal anything of what the secret cause of this horror is would be spoil things considerably – Weapons works best the less you know about it. But it’s not a spoiler to say there are dark forces at play – Weapons clues you in fairly quickly that a creepy house, with newspaper coated windows, is likely to be the centre of what nightmares may come. A big part of this is a performance of crazy off-the-wall freakishness by Amy Madigan, a gift of a role she rips into with gusto, an eccentric presence dripping with unsettling menace, both vicious and then eerily calm. Madigan bites into the role like Hopkins did Lecter, doing terrible things with a calm smile, making threats with calculated menace. Genuinely terrifying, truly memorable.

Weapons opens up a pot of terrifying, unsettling nightmare fuel. From the unnervingly unreal way the children run (arms trailing behind them) to background events that carry real terror. But there are moments of black comedy in here as well: the final sequence is both blood-soaked horror and also darkly hilarious (Cregger using distanced perspective shots to expert effect) and a housebound fight plays like a horror-slapstick. The main success of Weapons is it’s creeping sense of menace, the unsettling thought of horrific dark powers just on the edges of reality, that lack any sense of morality or decency. That what we can’t imagine is even more terrifying than what we can.