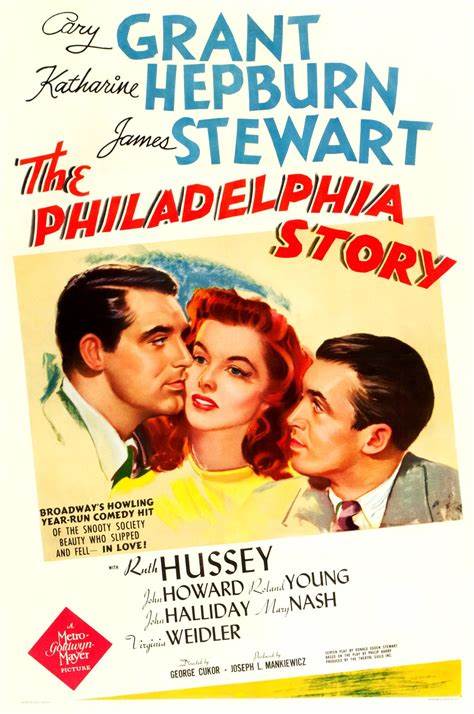

Three stars are at the top of their game in this classic screwball-style comedy

Director: George Cukor

Cast: Katharine Hepburn (Tracy Lord), Cary Grant (C.K. Dexter Haven), James Stewart (Mike Connor), Ruth Hussey (Elizabeth Imbrie), John Howard (George Kittredge), Roland Young (Uncle Willie), John Halliday (Seth Lord), Mary Nash (Margaret Lord), Virginia Weidler (Dinah Lord), Henry Daniell (Sidney Kidd)

In 1938 Katharine Hepburn’s career was over. After the flop of some now forgotten (wait, hang on…) screwball comedy called Bringing Up Baby, she took centre place on the Independent Theatre Owners list of “Box Office Poison”. Flops after flop hit Hepburn (all of them are classics today of course), and the studios did their damnedest to drop her. So, Hepburn returned to the stage, developing The Philadelphia Story with Philip Barry – and creating a lead role for herself that would play to all her strengths and help win back public affection. And which (with a little help from Howard Hughes) she would own the rights for: so, if and when they wanted to make a film, she could insist she starred. The rest is history.

The Philadelphia Story is perhaps the best example of the Code-approved genre, the “remarriage comedy” (because the code wouldn’t countenance the idea of a couple cheating). Daughter of a rich Philadelphia family, Tracy Lord (Katharine Hepburn) is to marry her dull fiancée George Kittredge (John Howard). George’s main attraction is he’s the complete opposite of her charismatic ex-husband C.K. Dexter Haven (Cary Grant). Dexter crashes the build-up to the wedding, bringing along reluctant society journalist (he’s really a renowned short-story writer) Mike Connor (James Stewart) and press photographer Elizabeth (Ruth Hussey), promising to introduce them as distant friends of the family so they can report on the wedding. But then Tracy finds herself drawn to Dexter and Mike and George as well – who will she end-up walking down the aisle with?

Perhaps the best thing about The Philadelphia Story is that you really don’t know who it will be – and the film successfully keeps the question both up-in-the-air and deeply entertaining. There even seems a chance (unlikely as it is) that Tracy really will stick with George (a tedious nouveau riche businessman with priggish middle-class morals who can’t even mount a house – imagine!). Directed with the sort of unfussy smoothness Cukor excelled in – and helped get the best out of actors – it’s a superb comic treat, with a sparkling adaptation by Donald Ogden Stewart.

At the heart of it, Hepburn is superb in a role that riffs considerably off her own public personality. Hepburn was smart enough to know most audiences saw her as far too clever by half. Her sharpness, acidity and no-nonsense unwillingness to suffer fools had made her hard to relate to. Quite correctly, she felt she needed a role where she could “fall flat on her face”. Which , by the way, is more or less the first thing she does – a hilarious prat fall while throwing Cary Grant’s Dexter out, him responding to her snapping his golf clubs by gently putting his hand on her face and pushing her off-balance (only Grant could have got away with that by the way).

Tracy Lord is a version of the Hepburn many people felt they knew. Tracy genuinely believes she’s smarter and better than anyone else, with unquestionable judgment and superior morals. The film is a gentle exercise in pricking her balloon, showing her she is as prone to mistakes, prejudice and, above all, getting giddy and silly in love, as anyone else. This is a fiercely practical woman, who sets high standards for those around her, suddenly finding herself falling in love with three men at once. It’s the exact flighty lack of commitment she spent years condemning her estranged father for.

This is all scintillatingly played by Hepburn, at her absolute best. The rat-a-tat dialogue (with its classic, Wildean comedy of errors and mis-identification) is under her complete control. She’s delightful when, under the influence, she flirts with Mike – Hepburn showing the world (clearly they missed it in Bringing Up Baby) that she could be as silly and vulnerable as the next girl. Hepburn knew people wanted to see her personae deconstructed, and for her character to learn that (in the words of another comedy) nobody’s perfect. It works a treat – and this remained one of her greatest (and funniest) performances.

It helps she had two of the greatest to riff off. Cary Grant is at his light-comedic best here, turning Dexter – a manipulative reformed alcoholic it would be easy to dislike – into the embodiment of sophistication, charm and playful wit, who we adore as much Tracy’s family does. James Stewart won an Oscar and matches Grant gag-for-gag in a comedic masterclass. He’s a master of hilarious comedic and physical reactions – and lovable enough to turn a chippy newspaperman into a sort of hilariously droll sage. His ‘drunk’ acting is also some of the funniest you’ll see on film (even Grant can be spotted cracking up just a little as Stewart hiccups his way through a scene).

Hepburn’s chemistry with both actors is sublime. Her romancing scenes – both the worst for wear for drink, but also empowered to say things they’ve clearly been burying all day – with Stewart are not hugely romantic, but also rather sexy (Cukor’s direction here is also exquisitely spot-on). It’s a masterclass in on-screen flirtation – and you can see why George gets as pissed off as he is. Hepburn and Grant meanwhile bicker and taunt each other with all the chemistry of a match and a fire.

Each scene has a bounce that teeters between heart-felt and farcical. The set-ups are frequently silly – but they work because they hinge on characters that feel immensely real. Every performer is spot on – credit also goes to a superb Ruth Hussey, one of the few grown-ups in this weekend of flirting, feuding children. Set in a sumptuously rich Philadelphian mansion, for all of Mike’s chippy criticism it’s a celebration of the smooth upper classes over hard-working, dull prigs like George. Its sole fault might be it’s too long (at just under 2 hours, a few scenes and set-ups outstay their welcome). But, as a classic Hollywood comedy, it’s pretty much the top of the class. Box-office poison no more.