Tediously reverent version, lacking drama and energy with two miscast leads

Director: George Cukor

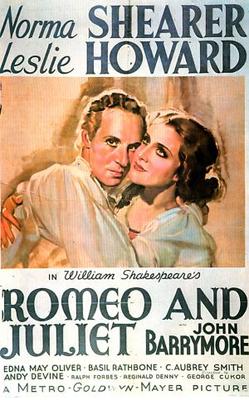

Cast: Norma Shearer (Juliet), Leslie Howard (Romeo), John Barrymore (Mercutio), Edna May Oliver (Nurse), Basil Rathbone (Tybalt), C. Aubrey Smith (Lord Capulet), Andy Devine (Peter), Conway Tearle (Prince Escalus), Ralph Forbes (Paris), Henry Kolker (Friar Laurence), Violet Kemble-Cooper (Lady Capulet), Robert Warwick (Lord Montague), Reginald Denny (Benvolio) Virginia Hammond (Lady Montague)

In The Hollywood Revue of 1929, Norma Shearer takes part in a comic skit as Juliet alongside John Gilbert, where they play the balcony scene in modern slang. It clearly gave her a taste for the role, since six years later she and powerhouse-producer husband Irving Thalberg bought the play to film for real. And not just any production: this cost north of $2million, hired an army of cultural consultants and was determined to prove Hollywood could do the Bard. It’s bombing at the Box Office (despite Oscar nominations) meant it would be years before Hollywood tackled Shakespeare again.

And you can see why. Decades later, Cukor called it the one film he’d love to get another go at, to get “the garlic and the Mediterranean into it”, by which I guess he means the spice. This production of Shakespeare’s play of doomed love is singularly lifeless, painfully reverential, lacks almost any original ideas, labours several points with on-the-nose obviousness and slowly curls up and disappears into a miasma of uncomfortable actors dutifully reading poetry. Is there any wonder it’s been lost by time?

It’s all particularly sad since it starts with something approaching a bang (once it gets the earnest, classical-inspired credits and list of literary consultants out of the way). Cukor stages the opening brawl between the Capulets and Montagues with a certain pizzazz, missing from almost all of the dialogue-heavy scenes that follow. Perhaps it was felt a dust-up in a lovingly detailed recreation of Verona, with sword fights and slaps, was far less stress for Hollywood folks who saw this as their bread-and-butter?

Either way, it’s an entertaining opening that grandly stages two lavish parades of the rival families arriving in parallel processions to a church, Dutch angles throw things into tension while extras whisper “It’s the Capulets! It’s the Montagues!”. The fight, when it comes (provoked by Andy Devine’s broad Peter, with his whiny, creaking voice and slapstick thumb biting) is impressive, with lashings of a Curtiz action epic, rapidly consuming the whole square in violence. Romeo and Juliet certainly puts the money on screen here – just as it will do later with a costume-and-extras-laden Capulet ball. Briefly, you sit up and wonder if you are in for an energetic re-telling of the classic tale. Then hope dies.

It dies slowly, under the weight of so much earnest commitment to doing Shakespeare “right” that all life and energy disappears from the film. Suddenly camera work settles down to focus on dialogue mostly delivered with a poetical emptiness that sacrifices any beat of character or emotion in favour of getting the recitation spot-on. That extends to the sexless, sparkless romance between our two leads, neither of whom convince as particularly interested in each other, let alone wildly devoted to death.

It doesn’t help that both leads are wildly miscast. It’s very easy to take a pop at them for being hideously too old as teenage lovers (Howard’s lined face looks every inch his forty plus years). But, even without that, both are brutally exposed. Ashley Wilkes is no-one’s idea of a Romeo, and Howard’s intellectually cold readings make him a distant, tumult-free lead it’s hard to warm too. His precision and cold self-doubt make him more suitable for a Macbeth, a thought it’s impossible to shake as he sets about his own destruction with a fixated certainty.

For that matter Norma Shearer would probably have made a better Lady Macbeth. Instead, she makes for a painfully simpering, vapid Juliet. She tries so hard to play young and innocent, that she comes across as a rather dim Snow White (not helped by her introduction, playing with a deer in the Capulet’s garden). Her ‘youthful’ mannerisms boil down to toothy grins and an endlessly irritating constant turning of her head to one side. Rather than making her feel younger, it draws attention to her age. It’s notably how much better she is in Juliet’s pre-poison soliloquy: even if her reading is studied, she’s better playing older and fearful than at any point as naively young.

Truth told, almost no one feels either correctly cast or emerges with much credit: except Basil Rathbone, clearly having a whale of a time as a snobbishly austere Tybalt (it’s joked this was the only time on screen Rathbone won a sword fight, and even then, it was only because Leslie Howard got in the way). Edna May Oliver mugs painfully as the Nurse, C Aubrey Smith makes Capulet indistinguishable from the army of Generals he had played. John Barrymore was allowed complete freedom as Mercutio, but his grandly theatrical gestures, camp accent and overblown gestures (not to mention looking every inch his drink-sodden fifty plus years) feel like he has blown in from an Edwardian stage.

Throughout an insistent score, mixing classical music and Hollywood grandness, hammers home the cultural and literary importance at the cost of drama. It’s combined with an increasingly painful obviousness. Romeo drops a dagger in Juliet’s bedroom for her to use later. Juliet lowers a rope ladder in expectation of an arrival of Romeo she can know nothing about. The Friar literally has a Frankenstein’s Lab cooking up industrial levels of his knock-out potion (what on Earth does he need this for? Investigation needed I think!). Poor Friar John gets a sub-plot we return to multiple times (to make the irony really clear) of being locked up in a plague house (“Hark ye! Help!” he cries, a fine example of the film’s occasional laughable mock-Shakespeare) as the other characters ride back and forth past the house oblivious to his vital news.

The whole production marinates in men-in-tights traditionalism, where the nearest thing approaching an interesting interpretative idea is Mercutio tossing wine up to some prostitutes on a balcony. Otherwise, all the beats you’d expect to see in a school production are ticked off – but done so on sets that cost a fortune, and in some impressive location setting filled with hordes of costumed extras. But it’s presented in a lifeless, passion-free, poetic sing-song; a dutiful homage, that drains all meaning.

Romeo and Juliet feels like a very long film. Any cinematic invention has long-since disappeared by the end (where you are rewarded with a brief burst of expressionist lighting for the Apothecary and a decently moody, shadow-lit sword-fight in the Capulet tomb). It’s replaced with a dry, lifeless, reverential deference to the Bard, as if everyone in the film was either apologising for having the gall to make it or defensively trying to prove they were doing their best. Either way, it doesn’t make for a good film or good Shakespeare.