|

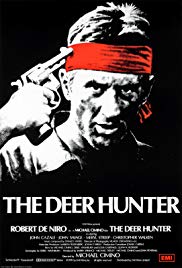

Robert De Niro goes into a journey into the dark heart of America’s Vietnam experience in The Deer Hunter

|

Director: Michel Cimino

Cast: Robert De Niro (Mike Vronsky), Christopher Walken (Nick Chevotarevich), John Savage (Steven Pushkov), John Cazale (Stan), Meryl Streep (Linda), George Dzundza (John Welsh), Pierre Sagui (Julian Grinda), Shirley Stoler (Steven’s mother), Chuck Aspregren (Peter Axelrod)

The Deer Hunter is a mighty 1970s milestone of American cinema. Michael Cimino’s Vietnam story is a big poetic epic – its plot is slim but it’s all about the atmosphere, and Cimino’s understanding of the impact that the trauma of war has on different types of men. For vast stretches of the film nothing much in particular happens, followed by short, sharp bursts of gut-wrenching tension – but these have such impact because we have taken the time to see these men’s ordinary lives.

Mike Vronsky (Robert De Niro), Nick Chevotarevich (Christopher Walken) and Steve Pushkov (John Savage) are three Polish-American friends working in a Pittsburgh steel yard, who have volunteered to serve in Vietnam. Before they ship out, they celebrate Steve’s wedding, in a traditional Polish ceremony, and go for one last deer hunt in the woods together – where Mike outlines his philosophy of “one clean shot” (or “This is This”) and the near sacred experience of man communing with nature and hunting. In Vietnam, the three friends are captured by the Viet Cong and forced to take part in a chilling competition of Russian roulette. The impact of these experiences changes their lives – and not for the better – as they struggle to adjust as the war comes to an end.

Michael Cimino was seen at the time as the next great director. This reputation lasted little more than two years, when the box office disaster of his next film Heaven’s Gate (with its tales of ludicrous excess and Cimino’s overly demanding perfectionism) led to the destruction of a studio and effectively ended his career. To be honest, the roots of all this are there in The Deer Hunter. Cimino fought tooth and nail to prevent anything in the film being cut – and he lucked out that he had a few supportive producers and a picture powered by great performances and capturing something of the spirit of the age. Because just this once, more was indeed more.

In some ways The Deer Hunter is an over-indulgent mess. It’s very long, its plot is very slight, it’s very pleased with itself, the camera dawdles for ages through first the friends preparing for a wedding, the wedding itself and then a long hunting trip. This takes up a solid opening hour and 15 minutes of this long film – and progresses the plot forward very little other than establishing the characters and their relationships. But somehow, despite this, the film is magnetic during this. I’m almost not quite sure why, because nothing really happens at great length, but there is a sort of poetic majesty about these sequences that just makes them work.

It’s also a perfect entrée into our characters. After basically sitting and watching them for over an hour do little more than live their everyday lives, we really feel like we understand them. We know Mike is distant, controlled, slightly repressed but prone to moments of exhibitionist wildness that suggest primal, raging emotions beneath the surface. We also understand, with his famous “this is this” speech (“what the fuck does that mean?” his frustrated friend-cum-adversary Stan blurts out), that he is reaching for some sort of symbolic, expressionist understanding of man’s place in the world. He wants to be a poet but doesn’t have the abilities of expression to achieve that.

Similarly, we see Nick as a more carefree, open spirit, someone more in touch with expressing himself and more ready to seize life by the horns. He’s also got a gentle, conciliatory quality to him – out of all the characters, he fits most naturally into the role of confidante. Steven is a child, just trying to do his best in the world, but too naïve for the grown-up world. Most crucially we also see how they interact with each other, and how they relate to women.

Most women in the film are clearly of very little importance to the characters. Wives and girlfriends are very much on the outskirts of the macho world of the steelyard. And they are of similarly little concern to the men when they come home. Meryl Streep – excellent in an almost nothing part, really it’s amazing how slimly this role is written – plays a woman torn between feelings for Mike and Nick, but the men’s feelings for her waver between uncertainty, indifference and confused affection. Barely any other woman gets a look in, certainly not Steve’s wife who is treated with open suspicion as some sort of floozy.

All this thematic manly matiness then explodes in the later acts of the film, as the after-impact of war – and PTSD, although the word is never used – hits our characters square in the face. And there are few things that will hit you as square on as a bullet. Cimino of course faced waves of criticism about his inclusion of the grisly gambit (no evidence that it was used by the Viet Cong) – but as a metaphor for going to war, and the trauma it will do to your mind, there are few things better than a “sport” which involves placing a gun to your head and pulling the trigger.

These scenes are already tension-inducing to watch (you can’t help but put yourself in the shoes of the men putting that gun to their heads and wondering if they’ll hear a click or nothing ever again) but Cimino ramps up the pressure here, helped by truly powerhouse performances by De Niro, Walken and Savage. The unbelievable intensity of these scenes, and the total gear shift from everything you’ve seen up to this point in the movie, is a justification of Cimino’s slow pace earlier. After a luxurious opening sequence where we’ve watched the guys fool around, dance, sing and play pool, to suddenly be thrown into this grim, despairing, terrifying situation works brilliantly.

No wonder the rest of the film feels as much in shock as the characters do. Walken is exceptional (and Oscar-winning) as the sensitive soul whose spirit and will to live are destroyed by the incident, who no longer sees any point going home and barely even (by the end) seems to remember who or what he was. Cimino even makes the film feel colder, drabber and chillier in the third act back in Pittsburgh, following Mike’s return home – and his utter inability to deal with his experiences or communicate the horrors of what he has gone through to his friends.

This is also where the film gains immeasurably from a truly sublime performance from De Niro as Mike. In any other actor’s career, this performance would be the stand-out, so it says a lot for De Niro that it’s so often overlooked. But he underplays to devastating effect, as an inarticulate, slightly shy man who has a sheen of confidence, who will do what it needs to survive, who has a poetry and power of love in him that he can’t really express or understand. De Niro is truly brilliant in this film, a still centre that bears almost the total weight of Cimino’s thematic intentions. Essentially De Niro kinda plays an everyman Vietnam vet, and the burden of a whole country after the war without ever having the release of fireworks. He’s excellent.

But then the whole film is a little bit excellent. The Deer Hunter is a masterpiece of a sort, a compelling, dark, tragic and unsettling piece of poetic movie-making. Saying that, there’s something uncomfortable in its depiction of its non-American characters – to a man they are all violence loving degenerates – but then in a film that focuses on the unsettling experience of these Hicksville Americans in a land they don’t understand and can’t deal with, this is at least justifiable in a sense. The Deer Hunter’s main problem at points is that it is a rather pompous, pleased with itself film, but it’s not so much the story that is so strong here but the telling – and Cimino’s telling is first class.