Subtle, low-key but powerful condemnation of oppression with a fabulous lead performance

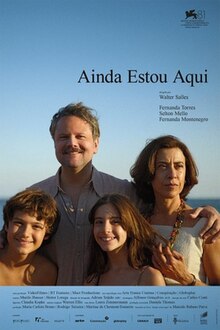

Director: Walter Salles

Cast: Fernanda Torres (Eunice Paiva), Selton Mello (Rubens Paiva), Guilherme Silveira (Marcelo Rubens Paiva), Antonio Saboia (Adult Marcelo Rubens Paiva), Valentina Herszage (Vera Paiva), Maria Manoella (Older Vera Paiva), Luiza Kosovski (Eliana Paiva), Marjorie Estiano (Older Eliana Paiva), Barbara Luz (Nalu Paiva), Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha (Older Nalu Paiva), Cora Mora (Maria Beatriz Facciolla Paiva), Olívia Torres (Older Maria Beatriz Facciolla Paiva), Pri Helena (Zezé), Fernanda Montenegro (Older Eunice Paiva)

In 1970 Brazil was controlled by a military dictatorship who tried to hide their unjust and violent methods from the public eye. Many people were taken from their homes to never be seen again, such as Rubens Paiva (Selton Mello), a former congressman and political opponent. Now working as a civil engineer, he is taken from his home by plain clothes military officers to help with unspecified enquiries. His wife Eunice (Fernanda Torres) is later also arrested, along with her teenager daughter, questioned and imprisoned for over a week then released with no word of Rubens fate. Eunice is left, bereft of answers as to what has happened to her husband, holding their family together, struggling for decades to try and get some sort of news of her husband’s fate.

Walter Salles’ heartfelt film captures the struggle of a whole nation to find answers in the story of one family – a story that achieved national fame in Brazil. And one personally known to Salles, who was himself (as a kid) a guest in the Paiva’s home and knew Rubens, Eunice and their children. His determination to tell this story with the dignity and truth it deserves is a major part of I’m Still Here’s success. It also gains real power from the focus it gives to the enduring difficulty of calmly, methodically rebuilding your families life in the face of terrible tragedy. As the title says, in many ways I’m Still Here is about persisting in the face of oppression, not letting your family collapse, to not just accept the new life forced on you, to carry on and not crumble.

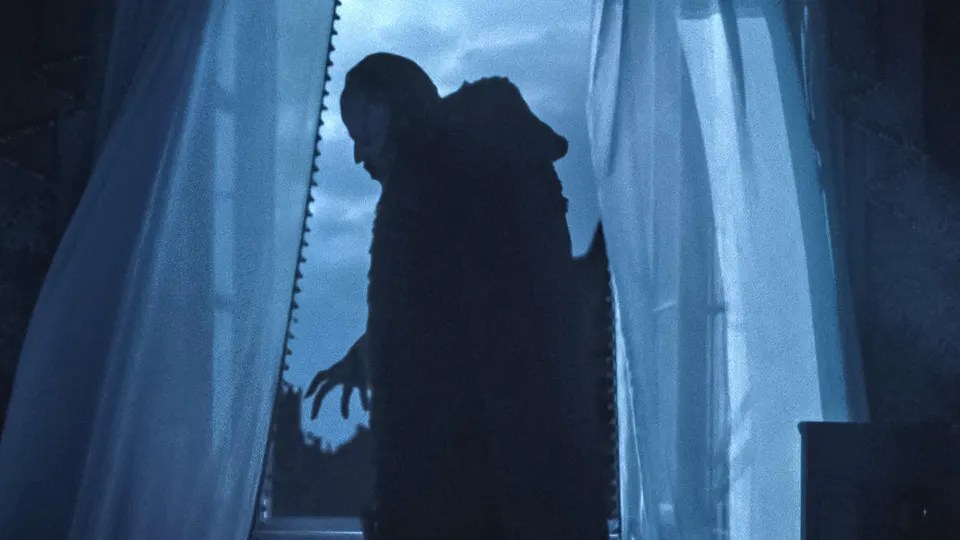

It does this by keeping the film surprisingly low-key. I’m Still Here deals in subtle intimidation, the velvet glove, more than it does the iron fist. The threat of approaching oppression is signalled subtly by the military helicopters flying loudly over Eunice’s head while she swims in the film’s opening. Her older daughter is part of a general stop-and-search out with friends that carries more than an air of possible violence. When the military police arrive, dressed informally, it’s not clear at first they are there to arrest Rubens. They are scrupulously polite and deferential and only show flashes of firmness (insisting no one else leave the home). The dictatorship’s method is to hide its brutality behind a screen of everyday politeness.

Salles condemns it using the same weapons, where the film’s underplaying helps it carry even more emotional force. There is very little in the way of either triumphal emotional beats or show-stopping speeches and no moments of horrific violence. Instead, this is a film where the triumph is dealing with your pain in such a way to protect what you can of your children’s innocence and defend what you have left. Fernanda Torres’ exceptional performance works on the basis of its quietness, its refusal to exhibit the wild emotional volatility others expect, but is full instead of the resolute determination to carry on in the face of everything life has to throw at you.

Torres’ performance is a masterclass in the small and subtle. This is a mother putting on a front of normality, only sharing a few words with her older daughters because the sheer danger of what is happening is not for ‘the ears of the little ones’. She is determined to protect as much normality for her young children as she can, and if this means she must hide in her husband’s office to shed a few tears before returning to fix her daughter’s doll and prepare her children for bedtime, she will. Because collapsing into grief and guilt is exactly what the dictatorship wants: it wants people cowed and scared, so Eunice will smile in the face of overwhelming adversity and pain.

It’s telling that I’m Still Here’s focus is less on Eunice’s campaign – of which we see very little: a few meetings, a photoshoot and a final reveal – and instead the quiet drama of salvaging a personal life from a world upside down. With her husband disappeared, Eunice literally cannot access their shared bank account (even when it is whispered to her that Rubens is dead, she still would need a formal death certificate to do this), with most of their savings tied up in a huge track of land Rubens had planned to develop. Suddenly their house, near to the beaches of Rio, can no longer be an open-doored haven: the location of a key that can lock their car gate turns from being forgotten to being essential. Throughout these quiet obstacles, you feel Fernanda Torres’ Eunice eternally stamping down the immense pressure to simply scream her pain and frustration out for all to hear.

There is a true nobility in this lowkey bravery. Only moments of horror creep in, such as the murder of a family pet. It feels particularly noble since, along with Eunice, we have seen a glimpse of the horrors. I’m Still Here’s prison sequence sees Eunice and her daughter escorted to a military facility with black bags over their head, for days of relentlessly focused interrogation in rooms devoid of daylight. For over a week Eunice only gains information about her daughter from snatches of clues from a sympathetic guard and listens from her cell to screams in a prison where even frequent washing can’t remove all the blood from the floor. This dictatorship hides its brutality, but only slightly, and if some of its agents seem polite they still unquestioningly follow cruel orders.

I’m Still Here flourishes in its focus on the everyday work to hold things together, that it almost doesn’t need its two codas one set in 1996 the other in 2014. But these briefer moments do provide true moments of power: the first seeing Eunice finally getting a copy of her husband’s certificate and the final featuring a powerful cameo from Fernando Montenegro (Torres’ mother) as an aged Eunice who, suffering from Alzheimers, finally lets a flash of her pain cross over her face. And while they seem at times to be gilding the lily, their presence re-enforces the courage involved in simply carrying on and preserving in the face of oppression, even over the course of many decades.

It’s that power that makes I’m Still Here, a quiet and unflashy film told with remarkable restraint, as effective as it is. Directed with a subtle but heartfelt hand by Salles, it also allows Fernanda Torres the room for a restrained but deeply moving performance that throbs with humanity. It’s quietness and calm in the face of oppression makes it a powerful indictment of dictatorship.