The popular image of Greece gets largely defined, for better and worse, in this flawed, over-long, tonally confused film

Director: Michael Cacoyannis

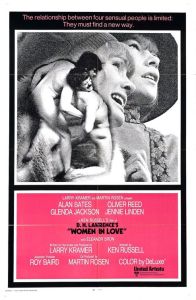

Cast: Anthony Quinn (Alexis Zorba), Alan Bates (Basil), Irene Papas (The Widow), Lila Kedrova (Madame Hortense), Sotiris Moustakas (Mimithos), Anna Kyriakou (Soul), Eleni Anousaki (Lola), George Voyagjis (Pavlo), Takis Emmanuel (Manolakas), George Foundas (Mavrandoni)

Basil (Alan Bates) a Greek-British writer, returns to Crete to try and make a success of his late father’s lignite mine and rediscover his roots. Joining him is Zorba (Anthony Quinn), a gregarious peasant, who believes in confronting the world’s pain with a defiant joie de vivre. In the Cretan village, their friendship grows and they become involved (with unhappy results) with two women: Basil with the Widow (Irene Papas), lusted after by half the village, and Zorba with ageing French former-courtesan Madame Hortense (Lila Kedrova).

Zorba the Greek was based on a best-seller by Nikos Kazantzakis, directed by Greece’s leading film director Michael Cacoyannis. Matched with Anthony Quinn’s exuberant performance, it pretty much cemented in people’s mind what “being Greek” means. So much so the actual film has been slightly air-brushed in the cultural memory. Think about it and you picture Quinn dancing on luscious Greek beaches. There is a lot of that: but it’s married up with a darker, more critical view of Greek culture that sits awkwardly with the picture-postcard tourist-attracting lens used for Crete.

Nominally it’s a familiar structure: the stuffed-shirt, emotionally reserved, timid and sheltered, is encouraged into a bit of carpe diem by a larger-than-life maverick. As is often the case, he needs t build the courage for romance and work on an impossible dream. Zorba the Greek however inverts this structure: the main lessons Zorba teaches is that you have to meet disaster just as you would meet triumph: with a shrug, a smile and a dance. It’s decently explored – and it lands largely due to Quinn’s barnstorming iconic performance – but also slight message. And Cacoyannis never quite marries it up successfully with the tragic consequences in the film.

Shocking and cruel events happen to the two female characters. The Widow – never named in the film – is loathed and loved by the men of the village, because (how dare she!) she’s not interested in sleeping with them. Played with an imperial distance by Irene Papas, she is condemned as a slut the second she does make a choice about who she welcomes into her bed (Basil, once). Madame Hortense (played with a grandstanding vulnerability by Oscar-winner Lila Kedrova) enters into a one-sided relationship with Zorba. Led to believe (by Basil) Zorba intends marriage, she becomes a joke in the village. Both women’s plot end with shocking, even savage, results.

A braver and more challenging film than Zorba the Greek would have used these events to counter-balance the light comedy and romance of the Greek vistas and Mikis Theodorakis’ brilliantly evocative score, by more clearly commenting on the darkness and prejudice at the heart of the village. In this Cretan backwater, lynching is perfectly legit, women are public property and even our heroes powerlessly accept what happens as the way of things. A smarter film would have pointed out that, in a savage land, Zorba’s ideology is essential or had Basil question his romantic view of Greece once confronted with the barbarism it’s capable of. Neither happens. Instead, the fate of these women is just another of life’s curveballs – the very thing that Zorba has been trying to train Basil to look past. They become learning points on our heroes journey.

Cacoyannis’ rambling script makes a decent fist at trying to capture the mix of Greek life and philosophical reflection that filled Kazantzakis novel. But he fails to bring events into focus or make any real point other than a series of picaresque anecdotes. Tonally the film shifts widely: a boat journey to Crete is played as slapstick, the eventual fate of the Widow chilling horror, the relationship between Zorba and Basil a buddy-movie tinged with the homoerotic. It’s a film that tries to cover everything and ends up not quite exploring any of its successfully.

It’s most interesting note today is homoeroticism. Helped by the casting of Bates, an actor whose screen presence was always sexually fluid (and who is excellent here), it’s hard not to think that Basil and Zorba are most interested in each other. Basil gets jealous, moody and lonely when Zorba leaves for weeks to fetch “supplies” from a local town. Zorba is equally fascinated by the twitchy and shy Basil, coming alive with him in a way completely different to the gruffness he shows to the other characters. Most happy in each other’s companies, there’s a fascinating homoerotic pull here that the film skirts around (not least by making sure both men have female love interests).

Basil is a curious character, strangely undefined and ineffective who listens a lot to Zorba’s messages but seems to learn very little. When the village turns on the Widow he watches like a lost boy. Zorba effectively takes over his home. The one time he tries to live life to the full, it leads to disaster. He remains strangely unchanged by events, which I am sure is not the films intention.

This misbalance is because the film really should be about him and the changes made to his life. It isn’t, because Quinn dominates the screen. A Latin American who most people thought was Italian or Arabic, here becomes the definitive screen Greek. Quinn’s performance here is his signature, grand, performative but also sensitive and strangely noble under the surface, a bon vivant just the right side of ham. He makes Zorba magnetic and hugely engaging and it says a lot that the Greeks effectively claimed him as one of their own. But he does seize control of the film and tips its balance away from its central figure.

Zorba the Greek is a crowd-pleaser, show-casing Greece, that skims on making a more profound impact on how beauty and savagery can live so close together. It doesn’t want to sacrifice the romance too much by staring too hard at the brutality. Tonally, Cacoyannis doesn’t successfully balance the film and its overextended runtime stretches its slight message. But, with its marvellous iconic score and wonderful performances, it’s got its moments.