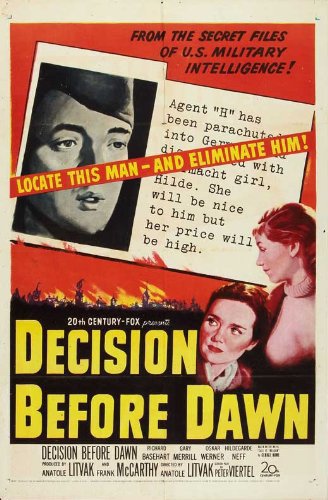

Tense war drama finds sympathy for the enemy, in an over-looked war film

Director: Anatole Litvak

Cast: Richard Basehart (Lt Dick Rennick), Gary Merrill (Colonel Devlin), Oskar Werner (Corporal Karl Maurer “Happy”), Hans Christian Blech (Sgt Rudolf Barth “Tiger”), Hildegard Knef (Hilde), Wilfried Seyferth (Henitz Scholtz), Dominique Blanchar (Monique), OE Hasse (Oberst von Ecker), Helene Thimig (Paula Scheider)

Decision Before Dawn tends to be remembered – if it is remembered – as an aberration in Hollywood history, one of the few films to receive only one nomination other than its Best Picture nod – with that nod generally put down to excessive Fox executive lobbying. I’d heard it described as a ‘fairly standard World War II film’ and expected it to be pretty disposable. But I guess I should have looked into things more: no less a director than Stanley Kubrick called it a hidden gem, claiming to have seen it five times. After a viewing, it’s hard not to think he might be right.

It’s a real, peeled-from-the-headlines tale. Shot entirely on location in Germany, in the very cities its characters are travelling through, still the bombed-out wreckage sites they were in 1944. With the assistance of (what was still then) the Occupying Powers, Fox and Anatole Litvak (himself a one-time refugee from the Nazis) recreated, to an astonishingly convincing degree, war-torn Germany six months before the death of Hitler, on locations littered with Germany military equipment. Everything in Decision Before Dawn feels astonishingly real because it largely is. When “Happy” tumbles through a bombed-out theatre or walks through bedraggled factories and grand houses converted to military bases, that’s the real thing.

Alongside this visceral sense of realism, is a surprisingly mature message. Helped by the presence of several German ex-pats, Decision Before Dawn casts a sympathetic eye over the Germans at a time when most of viewers would probably echo the initial sentiments of Richard Basehart’s scornful Lt Rennick: ‘they’re all just Krauts’. Rennick’s is part of an intelligence unit, tasked with ‘flipping’ German POWs and sending them back into Germany. Their two latest recruits couldn’t be more different: cynical Sgt Barth aka Tiger (Hans Christian Blech) motivated by earning a quick buck and thoughtful Corporal Maurer aka Happy (Oskar Werner) who believes Germany can only be saved when the madness of Nazism is defeated.

It’s Happy we follow when, after his recruitment, he is parachuted back into Germany and instructed to find the location of the XXth Panzer corp, while Rennick and Barth land further West to locate, and arrange the surrender of, a Wehrmacht Army Unit. Decision Before Dawn has already spent its opening act humanising erstwhile opponents via Happy. Happy is honest and principled with a strong sense of morality. He won’t lie to please his captors but he also won’t countenance the blind loyalty or bitter cynicism of his fellow prisoners. He is brave enough to save his country by ‘betraying’ it.

And it’s through Happy’s eyes we also see Germany. Many of his fellow POWs have no real love for Nazism; far from slathering fanatics, they are just guys knuckling down, wanting to stay alive. Behind-the-lines in Germany, the people Happy meets on his journey are striking in their everyday ordinariness. Decision Before Dawn’s most compelling sequences follow this ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ through the Reich, where episodic encounters mix with moments of panic and terror as a Gestapo net draws tighter.

The only two true believers he encounters are a glasses-wearing (it still loves some of the cliches) relentless Gestapo officer, and a Hitler Youth kid who still swallows true loyalty to the Fuhrer because he doesn’t know anything else. The others, by and large, are ordinary people trapped in a nightmare, trying to carry on. From a senior officer who reluctantly executes a deserter days before he knows the army will surrender to a depressed widow trying to make a living turning tricks. They are among a parade of regular citizens who, other than that fact they are commuting through a war zone, could be no different from Americans in their everyday concerns.

This places much of the film’s success on the shoulders of Oskar Werner, making his English-language debut. Werner, himself a deserter opposed to Nazism, brings the role a quiet, deeply affecting sincerity, expertly breathing life into a man who lives by his own firm moral code. ‘Happy’ deplores the taking of life but will do so if there is a reason: that won’t involve poisoning a colonel or standing by during the lynching of a POW by his fellow prisoners, but he will turn a gun on a direct threat. Werner makes him a thoughtful, compassionate man while giving him a strong streak (a Werner speciality) of in-built martyrdom, that a feeling he is too strait-laced and honourable for this world.

By making our hero a German – and the character we follow for almost the whole movie (despite Basehart’s top billing) – Decision Before Dawn is invites it’s American audience to emphasise with the enemy. To learn, alongside Rennick, that they are not ‘all Krauts’ so that we and Rennick can both be appalled by the unfairness when a Corporal mutters this at the film’s. That’s quite a thing for an American film, a few years after the war. By giving us handsomely staged spectacle centred around a man most of the audience were primed to expect to turn traitor, rogue or coward is no mean feat.

Of course, not every German can be good. The other potential recruits (one of them a young Klaus Kinski) are not a promising bunch and ‘Tiger’ (a fine, weasily performance by Hans Christian Blech) is betrayed as selfish, cowardly and perfectly happy to sacrifice anyone and everyone around him to ensure his safety. Litvak’s film does acknowledge it’s easier for the Americans to relax their feelings for the Germans than many of the other nations of Europe. Dominique Blanchar’s OSS officer makes it perfectly clear that, while she likes ‘Happy’, she’s still a long way from every imagining a relationship with a German of any sort.

Decision Before Dawn is well-directed, Litvak easing expert tension behind-the-lines and wonderfully shot among the ruins of Germany. Its final resolution may seem a little pat and obvious – and Basehart’s Rennick is such a terminally dull character I can only assume a host of more famous actors turned it down – but there is a lot of rich, fascinating tension and excitement here. Putting it frankly, Decision Before Dawn is a very pleasant surprise: a unique and mature war film that deserves far more recognition.