An independent woman finds romance in Venice in this luscious travelogue, one of the best of its genre

Director: David Lean

Cast: Katharine Hepburn (Jane Hudson), Rossano Brazzi (Renato de Rossi), Darren McGavin (Eddie Yaeger), Jane Rose (Mrs McIlhenny), Mari Aldon (Phyl Yaeger), Macdonald Parker (Mr McIlhenny), Gaetano Autiero (Mauro), Jeremy Spender (Vito de Rossi), Isa Miranda (Signore Fiorini)

American spinster Jane Hudson (Katharine Hepburn) has dreamed of her holiday-of-a-lifetime in Venice for as long as she can remember. So long in fact, that she wants to capture every single minute on camera and not miss a single sight in the gloriously romantic city. But there is more in this canal city than she expected, something her life of proud, self-sufficient, isolation has had little of: romance – namely from antiques dealer Renato (Rossano Brazzi), the two of them thrown together by chance, in a meeting of hearts and minds.

Summertime was, surprisingly, referred to by David Lean as his personal favourite of his films. It feels like an odd choice: the final film shot in the period between his ever-green 1940s British classics (and Summertime has echoes of Brief Encounter, from love affairs to train stations) and the super-epics that would fill the rest of his career. But, in its patient, quiet and slightly sad look at the continuous presence of regret in our lives and our feelings of loneliness, it perhaps speaks of something in the soul of this surprisingly vulnerable great director.

It won’t have hurt either that Lean himself fell in love with Venice during the shooting of the film. Summertime is very much in the genre of “romantic holiday travelogue” so beloved of the 1950s, when it was practically de rigeur to send glamourous Hollywood stars to exotic locations to conduct star-cross’d love affairs. Summertime might just be the finest of these, combining one of Hollywood’s all-time greats with a director and cameraman who made the setting truly cinematic, rather than the holiday snaps the journeymen who shot similar films reduced the locations to.

I’ll admit it helps I love Venice as well (and it’s amazing, watching this, how little the city has changed in the past 70 years). But Lean and gifted photographer Jack Hildyard shoot it with an intimate wonder. We follow Hepburn down the city’s winding streets and across its many bridges with a close intimacy that doesn’t shy away from the bustle of the city. A beautiful moment sees the camera slowly reveal the appearance of the St Mark’s Square campanile through an arched streetway. Carefully cut imagery flicks over striking features of Venetian architecture. Lean and Hildyard make the city feel like both a dream of a destination, but also a real, organic place, full of delightful nooks and crannies. It’s a masterclass in how to shoot a city both for impact and truth.

It’s a backdrop for an affecting, low-key, character study that gains hugely from the intelligent, emotionally precise performance from Hepburn. No actress in Hollywood could convince more as a woman full of enough brio and confidence to be very comfortable in her own solitude. The brilliance of Hepburn though is to play this all as a carefully maintained front shielding a loneliness she is always aware of but doesn’t want to acknowledge. It’s there from her compulsive need to make conversation with a fellow passenger (a lovely uncredited cameo from André Morell) on the train into the city, or with the people she meets at her hotel. The desire for human contact fills the easy rapport she builds with street urchin Mauro (a lovely performance from Gaetano Autiero) or the awkwardness she feels sitting alone in the bustle of St Mark’s.

It’s why romance – or perhaps the lack of it in her life – creeps up on Jane. Her first chance encounter with Renato is at a café in St Mark’s when he signals down the waiter she’s struggled to catch the eye of, leaving her discombobulated and uncomfortable, as if surprised that a man has taken even a passing interest in her, and uncertain how to respond. She retreats and sit on the canal-side, her eyes caught by a lion-headed drain that water laps in and out of. Perhaps only Hepburn could turn such a small moment into one of such profound passing reflection – and Lean shoots it with a beautiful simplicity.

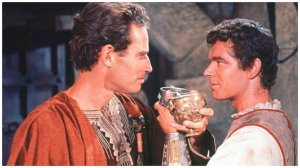

The relationship slowly builds as she happens to chance on Renato’s antiques shop and he sells her an 18th-century Venetian red glass goblet. Hepburn has a beautifully sensitive, almost girlish tentativeness to her as they walk idly together the next night through the streets. After they kiss under a bridge, she impulsively mumbles she loves him and then runs, as if she was startled by her own confession. The next night she prepares to meet him with a pampering session not out of place in a teen drama, sitting waiting for him with a giddy excitement.

As her beau, Rossano Brazzi has a wonderful unknowable quality to him. There are touches of his own sensitivity and isolation. There is also the worry, as he sits with cosmopolitan ease at a café table or (possibly) flogs Jane a worthless red glass goblet (she later discovers they are ten a penny, though he swears his is a genuine antique) that he could be a heartless roué. Jane worries it as well. But does she care? After all, this is a holiday-of-a-lifetime and perhaps a love affair is just part of that. It might well be the same for Renato: like Brief Encounter, two lonely people who recognise qualities in each other come together for a brief time, to find a little comfort. Let the fireworks explode (which Lean literally does in one more-than-suggestive cross-cut late in the film).

Summertime is very romantic, but it’s also very true. Both Jane and Renato know exactly what they are getting going into this: a blissful moment in time, but not a lasting commitment. There is something very true about this: and a pleasing acknowledgement that independence isn’t a condition to be fixed, but a state that allows bursts of companionship in between voyages of self-contentment. It’s mixes this with touches of humour (Hepburn sportingly performs a pratfall into the Venetian water – although it left her with an eye infection that troubled her for the rest of her life).

It’s possibly the finest travelogue romance ever made, very well paced and gently but handsomely filmed by Lean. Hepburn gives a stunningly intelligent, gentle and wise performance and its honest look at loneliness and passing regret at that loneliness – but still being contented at the choices you have made in life – also make it perhaps one of the most realistic and true-to-life.