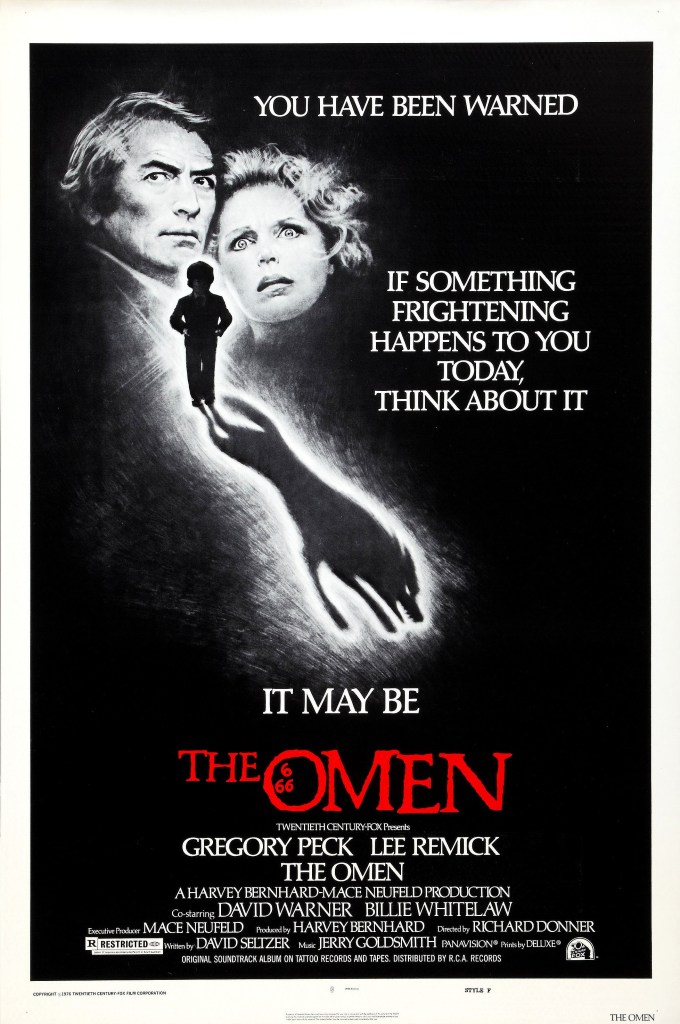

Extremely silly horror with a great score, more interested in inventive deaths and genuine fear or dread

Director: Richard Donner

Cast: Gregory Peck (Robert Thorn), Lee Remick (Katherine Thorn), David Warner (Keith Jennings), Billie Whitelaw (Mrs Baylock), Patrick Troughton (Father Brennan), Leo McKern (Carl Bugenhagen), Harvey Stephens (Damien Thorn), Martin Benson (Father Spiletto), Robert Rietty (Monk), John Stride (Psychiatrist), Anthony Nicholls (Dr Becker), Holly Palance (Nanny)

“Let him that hath understanding count the number of the beast; for it is the number of a man; and his number is 666.” One of the sweetest things about The Omen is that the number of the Beast was considered such an unknown concept to original viewers, that its painstakingly explained to us. In some ways The Omen is quite sweet, a big, silly Halloween pantomime which everyone involved takes very seriously. If The Exorcist was about tapping into primal fears, The Omen is a gory slasher (with a cracking score) that’s about making you go “Did you fucking see that!” as actors are dispatched in inventively gory ways. It’s brash, overblown and (if we’re honest) not very good.

Robert Thorn (Gregory Peck, selling every inch of his innate dignity for cold, hard lucre) is an American diplomat told one night in Rome that his pregnant wife Katherine (Lee Remick) has given birth to a stillborn child. “Not a problem” he’s told by an absurdly creepy Priest (Martin Benson) – just so happens there’s another motherless new-born child in the hospital tonight so he can have that one, no questions asked, and his wife need never know. Flash forward five years: Thorn is Ambassador to the Court of St James and young Damien (Harvey Stephens) is a creepy kid, with few words and piercing stare. In a series of tragic accidents people start dying around him. Could those people warning Thorn that his son is in fact the literal anti-Christ himself, be correct?

Want to see how powerful music can be? Check out how The Omen owes nearly all the menace it has to it imposing, Oscar-winning score from Jerry Goldsmith (wonderfullyGothic full of Latin-chanting and percussive beats). It certainly owes very little to anything else. The Omen is an exploitative, overblown mess of a film, delighting in crash-zooms, jump-cuts and extreme, multi-cut build-ups to gore. Richard Donner never misses an opportunity to signpost an approaching grisly death, by cutting between the horrified face of the victim, the object of their demise and then often back again. For the best stunts – including a famous demise at the hands of a sheet of glass – Donner delights in showing us the death multiple times from multiple angles.

This slasher delight in knocking off actors – people are hanged, impaled, crushed and decapitated in increasingly inventive manners – is what’s really at the heart of The Omen. None of this is particularly scary in itself (with the possible exception of the hypnotised madness in the eyes of Holly Palance’s nurse before her shocking suicide at Damien’s birthday party) just plugging into the sort of delight we take in watching blood and guts that would be taken in further in series like Halloween (which owed a huge debt to the nonsense here). Donner isn’t even really that good at shooting this stuff, with his afore-mentioned crude intercutting and even-at-the-time old-fashioned crash zooms.

With Goldsmith’s score providing the fear, The Omen similarly relies on its actors to make all this nonsense feel ultra serious and important. They couldn’t have picked a better actor than Gregory Peck to shoulder the burden of playing step-dad to the Devil’s spawn. Peck has such natural authority – and such an absence of anything approaching fourth-wall leaning playfulness – that he invests this silliness with a strange dignity. Of course, Atticus Finch is going to spend a fair bit of time weighing up the moral right-and-wrongs of crucifying with heavenly knives the son of Satan! Peck wades through The Omen with a gravelly bombast, managing to not betray his “for the pay cheque” motivations, and investing it with his own seriousness of purpose.

Peck’s status also probably helps lift the games of the rest of the cast. Lee Remick may have a part that requires her to do little more than scream (and fall from a great height twice) but she does manage to convey a neat sense of dread as a mother realising her son is not quite right. David Warner gives a nice degree of pluck to a sceptical photojournalist (while also bagging the best death scene). Troughton and McKern ham it up gloriously as a drunken former devil-worshipping priest and an exorcist archaeologist respectively. Best in show is Billie Whitelaw who filters her Beckettian experience into a series of chillingly dead-eyed stares as Damien’s demonic nanny.

The Omen does make some good hay of its neat paedophobia. Harvey Stephens with his shaggy hair, impish smile and pale skin (not to mention darkly sombre wardrobe) looks like your worst nightmare – he’s creepy enough that the film doesn’t need to gift him a vicious rottweiler as well. Donner’s decision to never have Damien show a touch of any real emotion for most of the film also pays off, meaning even something as silly as Damien inflicting slaughter from behind the pedals of a child’s tricycle seems scary.

Of course, if Damien was savvy enough to present himself as a bright and sunny child perhaps Troughton, Warner, McKern and co would have struggled to convince Peck he was the Devil’s seed. In that sense he takes after his dad: Satan loves an over-elaborate death, and from a storm herding one victim to a fatal impalement under a tumbling church spire to popping the handbrake of a glass-bearing van for another, no trouble is too much for Satan when bumping off those who cross him. (The Omen could be trying to suggest that maybe everything is a freak accident and Thorn goes wild and crazy with grief – but that Goldsmith score discounts any possibility other than Damien is exactly what we’re repeatedly told he is.)

The Omen trundles along until its downbeat, sequel-teasing ending, via a gun-totting British policeman who sticks out like a sore thumb in a country where the cops carry truncheons not pistols. Donner balances the dialled up, tricksy, overblown scares with scenes of po-faced actors talking about prophecies and the apocalypse, all shot with placid straight-forwardness. There is a really scary film to be made here about finding out your beloved son is literally a monster, or how a depressed father could misinterpret a series of accidents as a diabolical scheme. But it ain’t The Omen – this is a bump-ride of the macabre. The Devil may have the best tunes – but he needs to talk to his Hollywood agent.