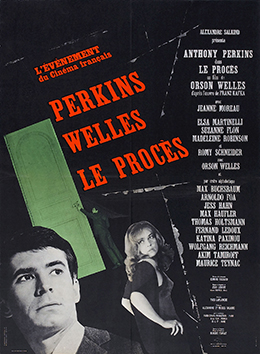

Welles exploration of paranoia and guilt is an easier film to admire than like (or enjoy)

Director: Orson Welles

Cast: Anthony Perkins (Josef K), Jeanne Moreau (Marika Burstner), Romy Schneider (Leni), Elsa Martinelli (Hilda), Suzanne Flon (Miss Pittl), Orson Welles (The Advocate), Akim Tamiroff (Bloch), Madeline Robinson (Mrs Grubach), Paolo Mori (Court archivist), Michael Lonsdale (Priest), Arnoldo Foa (Inspector A), Fernard Ledoux (Chief Clerk of the Court)

It had never happened to Welles before: in 1960 producer Alexander Salkind shoved a series of literary works at him and said “make one of these into a film! Money no object and complete creative control!”. Welles wasn’t going to say no. It hardly mattered that he’d barely even let Kafka cross his mind before: he could see a way to do The Trial and, by God, he wasn’t going to pass up this chance. To purists, The Trial is one of the few “pure Welles” flicks – the one Welles shepherded from start to finish and more-or-less ended up with what he wanted at the end of it (no wonder he called it “his best picture” – although he said that about all his pictures at one time or another).

The Trial adapts, fairly faithfully, Kafka’s surrealist novel. Josef K (Anthony Perkins), a middle-management pen-pusher, is accused of a terrible crime without being told what it is. He stumbles from encounter to encounter, law court to law court, never given the ability to defend himself, spiralling down the rabbit hole with no sunlight. Welles’ The Trial captures this by turning Kafka’s work into a fever dream. Scenes link together with all the structural logic of a dream – locations seem randomly connected, with Josef turning corners and finding himself in courtrooms or opening cupboards to find surrealist sequences like his prosecutors being whipped by an angry functionary.

Welles shot much of the film on location in a single abandoned Parisian railway station, with the abandoned, decaying rooms redressed into a series of locations from the Advocate’s rooms, to a church to a law court. This was mixed with sequences shot in Zagreb industrial estates and a factory set made up of 850 extras banging typewriters in unison and all rising to end their working day at the same time. There is a horrible un-reality reality to The Trial, a deeply unsettling realisation you are watching something both set in a world real and impossible.

In fact, The Trial may be one of the most uncomfortable films to watch ever made in its innate understanding of the domineering terror of paranoia. Welles used a series of low angles and wide lenses to stress the oppressiveness nearness of walls and ceilings. Rooms always seem to loom in and crush the characters, with K himself frequently framed hemmed in by objects, walls and people. There is a sense of being “watched” in every scene – either from the oppressive bodies that surround K, or the prowling tracking cameras that follow him from location to location.

The Trial is a sort of paranoid’s wet-dream, a nightmare world where logic is gone, our lead character has no control over his movements or destiny and the entire world seems to be constantly bearing down on him and us. Who better to play the twitch-laden centre of this than Anthony Perkins. Awkward, uncomfortable and never anything-less than tense, Perkins features in almost every scene but always feels buffeted by events rather than controlling them. He makes K hugely uncomfortable with others – the many women who throw themselves at K he treats with suspicion mixed with terror. His self-loathing bubbles up whenever confronted with mirror images (such as Akim Tamiroff’s timorous Bloch), invariably reacting with barely disguised contempt.

What’s also interesting in The Trial is the possible insight into Welles’ character. The easy interpretation is to see K as Welles, the court standing in for the Hollywood machine that had shoved Welles from pillar to post and never given him a chance. But, if so, why did Welles urge Perkins to play the role as shiftily and uncomfortably as he does? There is an air of guilt around K throughout – as if The Trial was his nightmare about getting caught for whatever he did. Is this how Welles saw himself? How fascinating that this artistic behemoth read The Trial and seemed to see it as the paranoia of a guilty man. Did the film speak to a deep self-loathing in Welles himself? Did he, in the dark when the demons come, think he’d inflicted his destruction on himself?

It’s a fascinating idea and makes it even more interesting that Welles is all over the film. He plays the corpulent, arrogant advocate, meeting supplicants whole luxuriating in bed with his accustomed bombast. But he also speaks the film’s woodcut-illustrated opening parable (a story of a man waiting at a gate, that he moved from the books Priest to his faceless narrator). Welles’ tones are heard coming from a range of mouths as he overdubbed many of his Euro actors. He even speaks the credits. Everywhere you turn you see and hear Welles and it’s hard not to start to feel perhaps we are stumbling inside his own terrible fantasies. Perhaps The Trial is what Welles’ dreams (or nightmares) were like?

The feel of a nightmare often makes The Trial an uncomfortable and, if I’m honest, less than enjoyable watch for all the undoubted panache it’s made with. In fact, since the panache is partly designed to illicit that response, it’s almost a tribute to the film’s success. The Trial is masterful, but in its unsettling sense of paranoia also uncomfortable, although it’s fascinating to see Welles layering some (perhaps inner) guilt on top of Kafka’s tale of an innocent crushed in the system. Either way, there is plenty to admire if not love about The Trial.