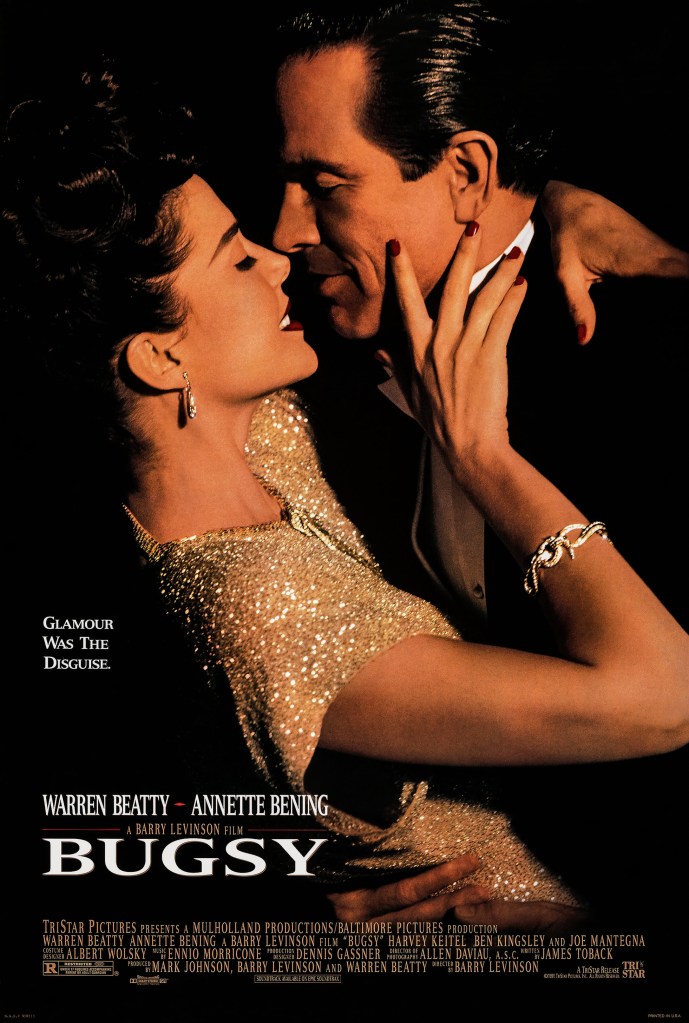

Old school glamour is the order-of-the-day in this luscious but slightly empty gangster film

Director: Barry Levinson

Cast: Warren Beatty (Ben “Bugsy” Siegel), Annette Bening (Virginia Hill), Harvey Keitel (Mickey Cohen), Ben Kingsley (Meyer Lansky), Elliot Gould (Harry Greenberg), Joe Mantegna (George Raft), Bebe Neuwirth (Countess Dorothy de Frasso), Bill Graham (Charlie Luciano), Lewis van Bergen (Joe Adonis), Wendy Phillip (Esta Siegel), Richard C Sarafian (Jack Dragna)

Las Vegas: the city of dreams for gangsters. As Ben (“Bugsy” – but don’t call him that) Siegel (Warren Beatty) tells a room full of gangsters when he’s pitching for their investment, like a hyper-violent Dragon’s Den: build the largest city in a state, you own the state, own the state and you own a slice of America. Imagine how the money can come rolling in then. It’s fair to say the mobsters aren’t so certain – and maybe Las Vegas would never have been a huge success if Bugsy had run it rather than being whacked – but God knows their investment paid out millions of times over.

The dream of building Las Vegas is at the centre of Beatty’s passion project (in this one he just played the lead and produced, dropping a couple of hyphens compared to Reds), a Golden-hued, romantic biopic of notorious gangster (and killer) “Bugsy” Siegel. Siegel sees what no-one else could see: how a city in a law-lax desert could become a mecca for gamblers, and crime could reap the profits. But the project goes millions over budget – not helped by girlfriend Virginia Hill (Annette Bening) creaming millions off the top. Trouble is Bugsy’s investors aren’t the sort of guys who shrug their shoulders at failed investments.

You can see what attracted Beatty to Bugsy. For all it’s about gangsters, I couldn’t escape the feeling Beatty sees Bugsy as something akin to a fast-talking movie producer. Bugsy spins elaborate stories for his backers of how their investment will pay-off, builds fantasies on a huge scale, won’t accept any compromise (a load-bearing wall should be knocked down if it’s blocking the view of the pool!), pouring his heart-and-soul into every detail of his vision. It doesn’t feel a world away from the same control-freak energy Beatty poured into Reds (Bugsy is basically financier, manager, backseat architect and marketing man for his dream).

Bugsy feeds a lot off the fascinating two-way admiration street between Hollywood and gangsters. Beatty’s Bugsy is enamoured with Hollywood, even shooting a (terrible) test reel to try and break into the movies. He’s thrilled to be hanging around with old pal George Raft (a muted Joe Mantegna), who seems equally jazzed to hook up with notorious criminals. Hollywood laps up the notoriety of criminals, both on-screen and off. For his Flamingo launch, Bugsy wants to stuff the place with stars (to his fury, bad weather prevents them arriving), and schmoozing celebrities is at least part of what is going to make the City of Sin such a fun place.

Levinson’s film is shot with a romantic lusciousness, a sepia-tinged nostalgia that wants you to soak up the glory of the costumes, sets and the cool of being a quick-witted gangster who gets all the best girls. It’s very different from the real Bugsy, a brutal killer with a huge capacity for violence. The film tries its best to match this, but can’t escape the fact that Beatty is way more suave and charming than Bugsy deserves. For all we’re introduced to him gunning down a cheating underling – and we see him brutally beat others for bad-mouthing Virginia or using his loathed nickname – he never feels like a brutal criminal, but more like a flawed, romantic dreamer with a temper.

It’s hard not to compare Bugsy with the best works of Scorsese from the same era. Goodfellas knew that, under the surface glamour, this was a dog-eat-dog world and that there was no romance at the end of a bullet. Casino (which followed a few years later, a sort of semi-sequel) sees the true vicious sadism and greed at the heart of this city-building operation, while Bugsy sees it more as a lavish dream and a tribute to a sort of visionary integrity. Even seeing Bugsy gunned down in his own home by a sniper, doesn’t carry with it the sort of inevitability it needs. As Scorsese understands, this way of life is like playing Russian roulette forever – eventually the chamber is going to be full. For all Bugsy literally plays roulette, it never feels like he’s playing with fire, more that he’s reaching slightly beyond his grasp.

Perhaps Levinson doesn’t quite have the vision to make the film come to life or stamp a personality on it. It feels like a film that has been carefully produced and stage-managed to the screen – and Levinson deserves credit for marshalling such an array of commanding personalities together to create such a lavish picture. But it’s muddled in its message. Is Bugsy actually worth making a film about? What are we supposed to understand from this: was he a killer out of his depth, or an unlucky dreamer? Bugsy wants him to be both, but fails to make a compelling argument for either.

Beatty is impressive in his charisma though, for all he never quite seems to have the edgy capacity for instant violence the part needs. He does capture Bugsy’s desire for self-improvement, from the Hollywood dreams to the eternal elocution lessons he repeats over-and-over like a mantra. His desire for glory even manifests as a bizarre fantasy that he is destined to assassinate Mussolini. It also perhaps explains why he’s drawn to Virginia, a would-be starlet. Annette Bening gives arguably the most impressive performance (but, inexplicably, was practically the only major figure involved in the film not to pick up an Oscar nomination) as a woman who is an unreadable mix of devoted lover and selfish opportunist, leaving us guessing as to her real intentions and feelings.

There is good support from Keitel (hardly stretching himself as Bugsy’s number two Mickey Cohen), Kingsley (an ice-cool but loyal Meyer Lansky, unable to stop Bugsy destroying himself) and, above all, Elliott Gould as Bugsy’s hopeless, pathetic best friend. Bugsy though, for all it’s entertaining, feels like a mispackaged biopic that wants to turn its subject into a romantic figure, unlucky enough to be rubbed out before he could be proved spectacularly right. This soft-soap vision doesn’t ring true and misses the opportunity the film had to present a more complex and nuanced view of the era and its crimes.

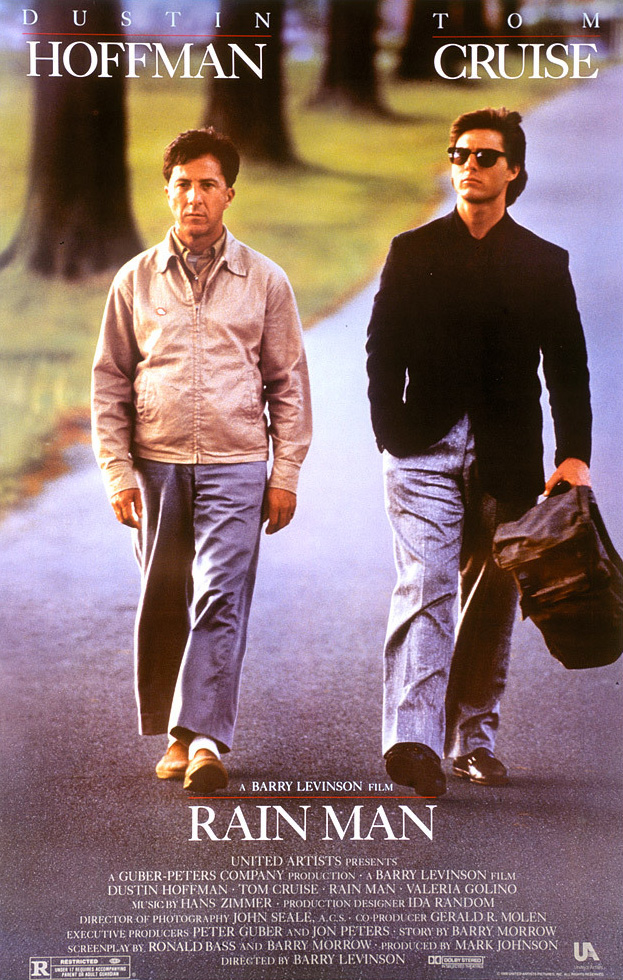

1988 wasn’t a vintage year at the Oscars, so perhaps that explains why this functional film ended up scooping several major awards (Picture, Director, Actor and Screenplay). Rain Man is by no means a bad film, just an average one that, for all its moments of subtlety and its avoidance of obvious answers, still wallows in clichés.

1988 wasn’t a vintage year at the Oscars, so perhaps that explains why this functional film ended up scooping several major awards (Picture, Director, Actor and Screenplay). Rain Man is by no means a bad film, just an average one that, for all its moments of subtlety and its avoidance of obvious answers, still wallows in clichés.