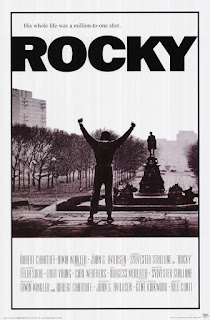

Doubters and some very steep steps are conquered in the Best Picture winning Granddaddy of Sports movies

Director: John G. Avildsen

Cast: Sylvester Stallone (Rocky Balboa), Talia Shire (Adrian Pennino), Burt Young (Paulie Pennino), Carl Weathers (Apollo Creed), Burgess Meredith (Mickey Goodmill), Thayer David (Miles Jergens), Joe Spinell (Tony Gazzo), Tony Burton (Tony “Duke” Evers), Pedro Lovell (Spider Rico)

How many people have run up those steps to the Philadelphia Museum of Art? So many, they’ve renamed them “the Rocky Steps” – and placed a statue of Stallone (from Rocky III) there. You can be sure everyone hummed Gonna Fly Now while they did it. It’s all a tribute to the impact of Rocky, the iconic smash hit that led to no less than seven sequels (and counting!) and, arguably, kickstarted the 80s in Hollywood (a decade Stallone would stand tall across with both Rocky and Rambo). The original Rocky mixes genre-defining delights and a feel-good, crowd-pleasing story with a surprisingly low-key setting that deals in a bit of Loachesque reality and social commentary.

Rocky Balboa (Sylvester Stallone) is a journeyman southpaw boxer, fallen on hard times. He’s making ends meet with a bit of loan shark enforcement (although of course he’s far too nice to actually break any bones) and getting seven bells knocked out of him at low-key fights. His trainer Mickey (Burgess Meredith) thinks he’s wasting his talent, and Rocky spends the day casting puppy dog eyes at Adrian (Talia Shire) sister of Rocky’s chancer best friend Paulie (Burt Young). But Rocky’s life changes overnight when Heavyweight Champion of the World Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers) picks him at random as the nobody he will fight in a title bout (to get Apollo some free publicity). Can Rocky dedicate himself to training so he can “go the distance”?

Surely everyone knows by now, don’t they? The big fight only takes up the last ten minutes of the film. What we’ve spent our time doing beforehand is watching possibly the one of the best ever packaged feel-good stories, full of lovable characters and punch-the-air moments, directed with a smooth, professional (but personality free) charm by Avildsen. Rocky genuinely looked and felt like a little slice of Capra, a fairy tale triumph for the little guy struggling less against the world and more against his own doubts.

And it overcame some real heavyweights to win Best Picture: it knocked aside All the President’s Men, Taxi Driver and Network in a shock win. Is Rocky better than those films? No. But is it more fun to watch? Yes, it probably is – and I would be willing to bet many more people have come back to it time and time again. It was also a triumph for Stallone, a jobbing actor, who produced a first draft of the script in three days and fought tooth and nail to make sure he played the lead.

And Stallone’s performance is absolutely central to its success (can you imagine what it would have been like with, say, James Caan in the role?). Stallone gives Rocky exactly the sort of humble, shy, sweetness that makes him easy to root for. Rocky is no genius, but he’s loyal, polite, well-meaning and Stallone taps into his little-used qualities of softness and naivety. Rocky is lovable because, for all the punching, he’s very gentle – just look at him make a mess of money collecting or the way he talks like a little kid with his pets. Stallone has a De Niroish – yes seriously! – quality here: he absent-mindedly shadow boxes throughout and gives a semi-articulate passion to his outburst at Mickey. His romance with Adrian is intimate and gentle. The whole performance feels lived in and real.

Real is actually what the whole film feels like – despite the fact it’s a ridiculous fairy tale of a boy who becomes a prince for a day. It helps that its shot deep in the streets of Philadelphia, on the cheap and on the fly in neighbourhoods and locations that feel supremely unstaged (Avildsen avoided the cost of extras by frequently shooting at night or very early morning). Even that run up the stairs was a semi-improvised moment. Rocky’s world is a recognisable working-class one that for all its roughness, also feels like a community in a way Ken Loach might be proud of (even the loan sharks are easy-going). Day-to-day the film manages to capture some of the feel of a socio-realist film with a touch of working-class charm.

It also makes a lovely backdrop to the genuinely sweet romance that grounds the film: and a recognition of the film’s smarts that a great crowd-pleaser needs a big dollop of romance alongside a big slice of action. Very adorably played with Talia Shire (original choices Carrie Snodgrass and Susan Sarandon were considered too movie-star striking), Adrian feels like a slightly mousy figure (and she is as sweet as Rocky) but also has a strength to her. She’s led a tough life as sister to the demanding Paulie (and Burt Young does a great job of making a complete shitbag strangely lovable and even a bit vulnerable), but it’s not stopped her feeling love. She and Rocky complement each other perfectly – gentle, shy people, who have something to prove to themselves and the world.

Is there a sweeter first date in movies than that solo trip to the ice rink? Cost cutting saved the day here (it was intended to be packed), that stolen few minutes skating while Rocky hurriedly tries to find out a much about Adrian as he can (an attendant counting down the time they have as they go), Adrian both charmed and bashful. It’s a lovely scene and goes a long way to us giving these characters the sort of emotional devotion that would keep audiences coming back for decades.

That and those boxing fights of course. Rocky’s final fight sets a template most of the rest of the films would pretty much follow beat for beat. But it’s still fun watching Rocky go toe-to-toe against all odds. Particularly as we know what is important to Rocky is not victory but proving something to himself. It helps as well that Stallone still looks like an underdog of sorts (over the next ten years he would turn himself into a slab of muscular stone).

Opposite him is Apollo Creed, with Carl Weathers channelling his very best Mohammad Ali. The underdog story makes for fine drama, and Rocky is superably packaged: there is a reason why so many other films essentially copied it. From montage, to an “against all odds” fight to Burgess Meredith’s grizzled trainer (a part you’d see time-and-again in the future from different respected character actors) there is a superb formula Rocky takes and repackages from classic films of the 40s and 50s and re-presents to huge and successful effect.

And it works because it’s so entertaining. Stallone is hugely winning in the lead role – more sweet and sensitive than he would be in later Rocky films (traits he would allow himself to rediscover in the more recent films) and it’s a perfectly packaged feel-good entertainment. But it’s also got a grounded sense of realism and reality, with an affecting love story. It’s one of the first – and best – films of the 80s, where formula and crowd-pleasing would be king.