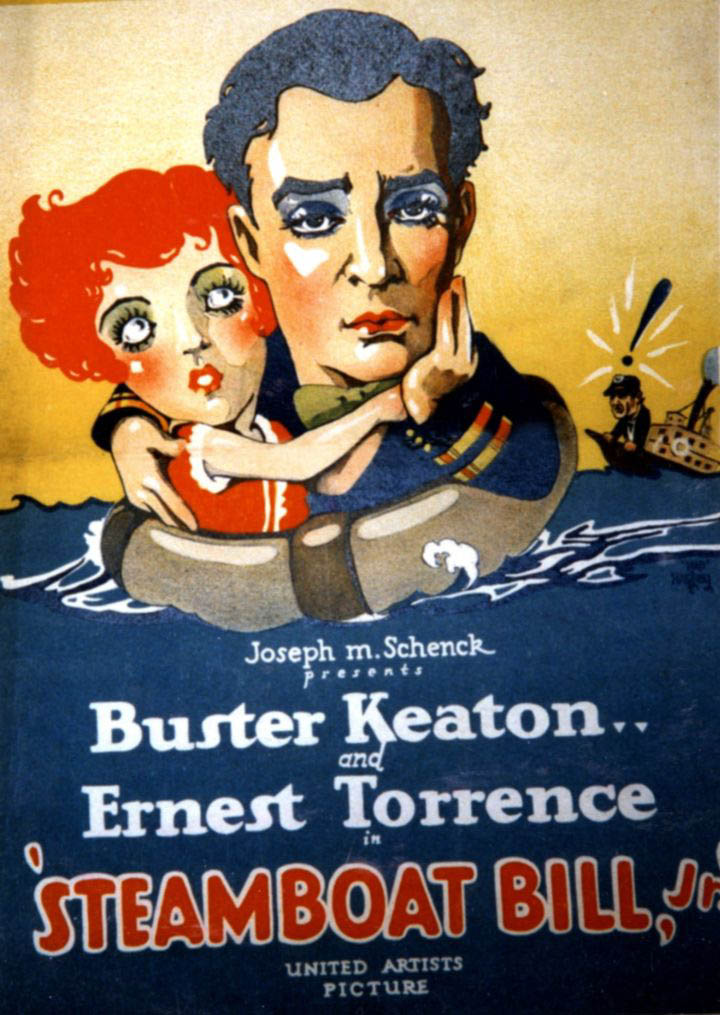

Keaton struggles to win his father’s approval in this brilliantly fast-paced farce

Director: Charles Reisner (& Buster Keaton)

Cast: Buster Keaton (William Canfield Jnr), Ernest Torrance (William Canfield Snr), Marion Byron (Kitty King), Tom McGuire (John James King), Tom Lewis (Tom Carter), Joe Keaton (Barber)

Steamboat Bill Jnr was meant to be a return to glory after the box-office disappointment of The General. Unfortunately for Keaton it shared all the traits of his previous film. An artistic triumph, today seen as one of the great silent comedies: but at the time an expensive misfire that hammered the final nail into Keaton’s filmmaking independence. Before he was swallowed by the MGM machine, Steamboat Bill Jnr was the last pure Keaton film, the last display of the master’s gravity defying stuntwork and all-in physical gag commitment.

Keaton is the forgotten son of paddle steamer operator William “Steamboat Bill” Canfield (Ernest Torrance) whose craft, the Stonewall Jackson, is being put out of business by the cutting-edge steamer The King named after its wealthy owner JJ King (Tom McGuire). William Jnr is a disappointment to his manly father: he’s clumsy, polite, decent has a pencil moustache (but not for long) and plays the ukelele. What kind of son is that? Worst of all, he falls in love with Kitty King (Marion Bryon), daughter of Steamboat Bill’s love rival. Can his son prove his worth when disaster piles on disaster and a cyclone hits the town?

Steamboat Bill Jnr is Keaton at his best. Although it has a romance plotline, this wisely plays second fiddle to the sort of role Keaton was born to play: slightly naïve and foolish sons, who are disappointments to their father. With his sad sack, impassive face and earnest, try-hard determination, Keaton was guaranteed to win the sympathies of the masses and Steamboat Bill Jnr is the fine-tuned ultimate expression of this classic Keaton role. He’s horrendously unlucky – he seems destined to trip over and activate vital levers or if he opens a door it will inevitable send someone tumbling off the boat – and at every turn well-meaning attempts to win his father’s favour backfire. It’s a superb exploration of a key theme in Keaton’s life and work – the struggle to win the regard of a domineering father in his own line of work, something Keaton had faced in his own life.

But despite that, like all the best Keaton heroes, he never, ever gives up. Adversity is milk-and-drink to him and, despite everything, his ingenuity and determination always wins out. He may look like a clueless, slightly ridiculous college kid adrift on a boat, walking around in his over-elaborate uniform: but the final reel, which shows him hooking up the boats systems via ropes and pulleys so he can control it singlehandedly proves it certainly wasn’t lack of attention that lay behind his mishaps.

And what’s really wrong with being a clearly middle-class kid who hasn’t spent much time on boats? It’s not like he’s a dandy or a layabout – he just doesn’t fit the mould his father expects – that of a flat-capped, oil-stained, tobacco chewer (and who knows not to swallow it!) never happier than when getting his hands dirty. Ernest Torrance is very good as this exasperated working-man, whose ideas of what counts as “manly” are very narrow (barely extending beyond the mirror) and sees any deviation in his son as highly suspicious metropolitan laxness.

Perhaps he feels his son looks too much like his puffed-up, slightly dandyish rival JJ King (an effective Tom McGuire). There is more than a touch of class warfare between these two, as well as a romantism that values the run-down-but-reliable Stonewall Jackson (right down to its Civil War era name) and the overly-polished-can’t-trust-it King. There are echoes (and not just in the names) in the generational family feud of Our Hospitality – not least in the fact that marriage seems destined to eventually bring the two families together in something approaching love and harmony.

Marion Byron gives a decent performance as Kitty – even if the film has little interest in her beyond love-interest device, including the inevitable moment where she becomes convinced Keaton’s character has let her down and decides to snub him. This snubbing takes place in a very funny scene of missed meetings and attempted evasions on the street; although this scene is itself a shadow of father and son meeting at the station, the son writing he will be recognisable by his white carnation, a flower everyone arriving at the train seems to be wearing (not helped by Keaton losing his).

Eventually matters proceed to blows and the arrest of Canfield Snr (and an attempted break-out foiled by the son’s inability to get his father to trust him) before the town is blown away in one of the great Keaton set-pieces. Rain and bad weather peppers the final thirty minutes of the film – including an exquisite sight gag when Keaton steps into a puddle and disappears up to his waist – and erupts into a cyclone that rips buildings apart, blows others across fields and raises the waters to wreck the paddleboats and wash other buildings out to sea.

And this storm is the centrepiece of another peerless display of Keaton’s physical determination and courage in the name of comedy. He gets trapped in a hospital bed blowing through the streets (after the building rips away to reveal him, a stunning in camera trick). He walks at almost 45 degrees against the wind. And, most famously, he stands in the perfect spot for the window of the façade of a house to save him when it falls on top of him. For this final stunt – insanely dangerous by any standards – even Keaton would later reflect on the suicidal risks he took. Either way, it’s a brilliantly elaborate set-piece (a riff on another set-piece from an earlier short) and a clear sign no-one did better than Keaton.

And no-one did. Watching Keaton bound like a squirrel up and down a paddle boat and dive into the flooded river, you know you are watching someone who really understand both the beauty of visual imagery and the peerless excitement of reality on film. Steamboat Bill Jnr combines this with a strong story, full of characters to root for and stuffed with sight gags (from a parade of hats stuffed on Keaton’s head, to a shaving from his father Joe) that make you laugh time and again. It’s a tragedy that this, one of his finest comedies, would also be his last where he had creative control.