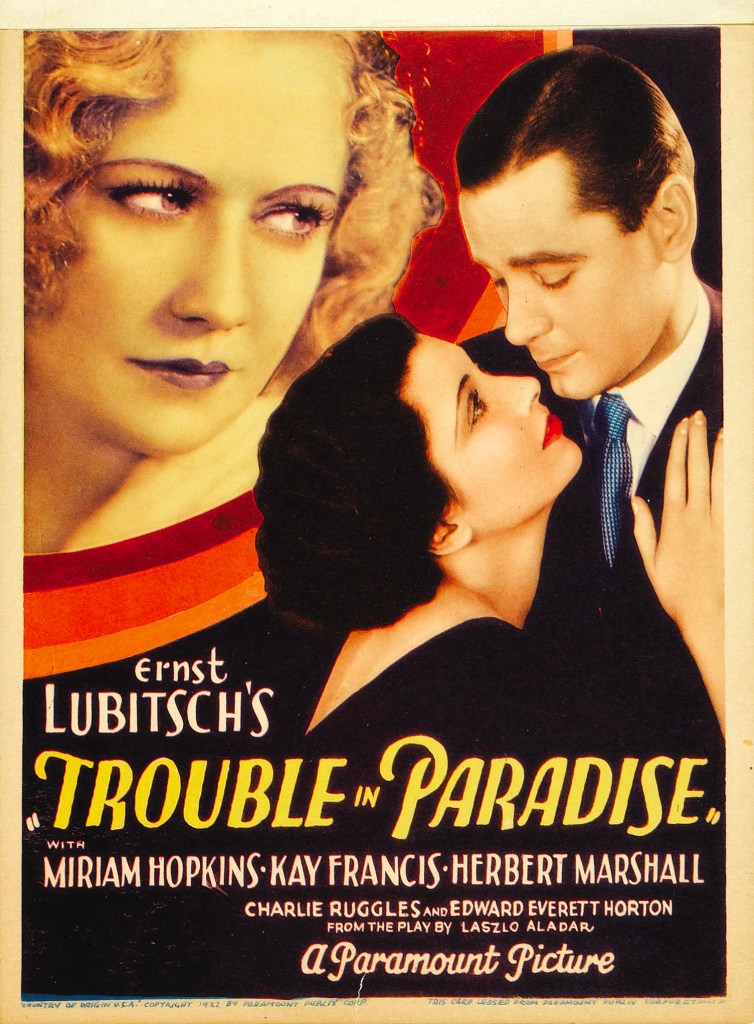

Stealing, swindling and sex abound in Lubitsch’s masterful – and influential – early Hollywood comedy

Director: Ernst Lubitsch

Cast: Miriam Hopkins (Lily), Kay Francis (Madame Colet), Herbert Marshall (Gaston Monescu), Charles Ruggles (The Major), Edward Everett Horton (Francois Filiba), C. Aubrey Smith (Adolph J Giron), Robert Greig (Jacques, the butler)

“Ah, that Lubitsch touch!” It was a slogan invented by the studio (probably to help turn Lubitsch into a brand – see also “The Master of Suspense!”). No one has ever been quite sure what it is exactly – but you can’t argue it doesn’t exist after watching Trouble in Paradise. A smoother, more charming slice of Wildean wit mixed with saucy naughtiness you couldn’t hope to find. All put together with effortless, cosmopolitan wit by Lubitsch, where every shot and camera movement has been planned for maximum effect. No wonder it’s one of the great early Hollywood comedies.

It’s Vienna and a Baron and a Countess are sitting down to a wonderful dinner together. But both know all is not what it seems: they’re both professional conmen. The Baron is Gaston Monescu (Herbert Marshall), the Countess Lily (Miriam Hopkins) – and they can pick each other’s pockets as easy as breathing. Falling in love, they team up and head for Paris, there to relieve fabulously wealthy Marie Colet (Kay Francis) of some of her firm’s dividends. Gaston becomes Marie’s private secretary – but don’t you know it, he finds himself falling in love with her. Will he go through with the scam? And will Lily give him the choice? The answer is almost certainly not what you think.

Trouble in Paradise is so swift, smooth and gloriously comically inventive that its very existence is enough proof of that Lubitsch touch. The comic business here is so marvellously done, so hugely influential and inventive, that half the comedies existing owe it a debt. Take a look at that first sequence as the two of accuse each other of being thieves and liars, in between passing each other the salt, with consummate politeness then proceed to take part in a pickpocketing game of one-upmanship (purses, pins, watches, garters, you name it!). All shot and directed with a perfect mixture of one-take dryness, matched with perfectly chosen fluid camera movements that accentuate punchlines.

Then there’s that script (“Do you remember the man who walked into the Bank of Constantinople and walked out with the Bank of Constantinople?”). It’s crammed to the gills with sensational bon mots with more than a touch of Wilde or Coward but also a certain emotional truth (“I came here to rob you, but unfortunately I fell in love with you.”). Trouble in Paradise is an intensely suave and sophisticated film that delights in making its characters feel like the nimble-thinking smartie-pants who always know what to say, that you’d love to be, but never quite are.

It’s grist to the mill of Lubitsch, who coats the film in the three things that really makes it work: European sophistication and ruthlessly dry wit; playfully smooth direction; and more than a dollop of sex (and lots of people in this, let’s face it, are pretty impure to say the least). Sex is in fact what’s at the heart of this film: they may be criminals, but Gaston and Lily are at least as interested in getting some of that as anything else and Marie is more than a match for them.

Trouble in Paradise is pre-Code – and far racier than anything we normally expect from Old Hollywood. After all, this is a film that makes a series of perfectly timed punchlines out of a Butler constantly knocking on the wrong bedroom door to find Marie, unaware that Gaston and Marie are “spending time together” elsewhere. Gaston and Lily’s first meeting is capped with a “do not disturb” sign being hung on their bedroom door. The word sex gets bandied about. In case we missed the point, Lubitsch shoots a romantic clinch between Gaston and Marie by focusing the camera on the bed where their shadows are being cast, looking for all the world like they are lying down on it. Later Lubtisch will focus on a clock marching forward in time as we hear Gaston and Marie flirt (and clearly more than just flirt) as the time flows by.

No wonder when the Code was introduced, Trouble in Paradise was slammed on the shelf for years. It’s more than clear that Gaston has it away with Marie and Lily – and, even more scandalously, no one seems to mind that much. There is sexual liberalness to Trouble in Paradise. Marie is happily stringing along two boorishly foolish suitors (Charles Ruggles as a bluff retired major and Edward Everett Horton as a slightly pompous fop, fleeced in the past by Gaston – both very funny). Gaston feels many things, but never ashamed, while Marie seems sexually excited by the idea that he might be a crook. (Their first meeting is a simmering swamp of sexual tension.)

Lubitsch keeps the film flowing so effortlessly, it glides down barely touching the edges. The humour is spot on and perfectly delivered. At one point Lily (still disguised as the Countess at this point) phones her “mother” in front of Gaston. Her conversation is polite and giddy – then Lubitsch cuts to the other end of the call where her crude landlady is prattling bored on the end, and we realise it’s all part of a con. Gags like this have inspired filmmakers for years. You can see the root of half the screwballs that were to come in the love triangle flirtatiousness between Marshall, Francis and Hopkins.

All three of them are excellent. Marshall had few better opportunities to showcase his dry wit and sex appeal (he was so often cast as stuffy, dull husbands), and he’s the ideal arch gentleman here, with a twinkle in his eye at his daring smartness and very sexy in his confidence. (The constant shots of Gaston running up and down stairs is, in itself, a gag – Marshall had only one leg and all that running was a body double). Far from a rube, Kay Francis makes Marie a sexually curious, determined and out-going woman who knows what she wants and happily plays the game to get it. Miriam Hopkins has a punchier feistiness as a woman who can shift personae with effortless ease.

Trouble in Paradise – that Paradise being Gaston and Lily’s natural partnership – slides so smoothly from set-piece to set-piece, each of them shot with superbly smooth camera movements that perfectly accentuate their comic impact, that it continues to offer huge entertainment. Brilliantly acted, packed with superb set-pieces, it benefits above all from that glorious Lubitsch touch. Sophisticated, amoral, naughty but with a touch of heart among all the lying and cheating, it’s very funny and very cheeky and all about sex and stealing. It’s a landmark film.