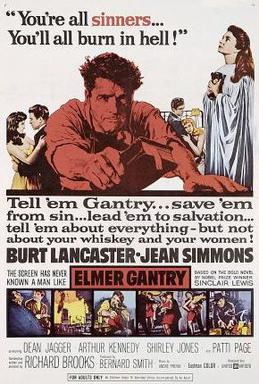

Burt Lancaster gives a magnetic, Oscar-winning, performance in this entertaining plot-boiler

irector: Richard Brooks

Cast: Burt Lancaster (Elmer Gantry), Jean Simmons (Sister Sharon Falconer), Arthur Kennedy (Jim Lefferts), Dean Jagger (William L. Morgan), Shirley Jones (Lulu Bains), Patti Page (Sister Rachel), Edward Andrews (George F Babbitt), John McIntire (Rev John Pengilly), Hugh Marlowe (Rev Philip Garrison), Joe Maross (Pete)

Elmer Gantry (Burt Lancaster) has the patter down perfectly. He can charm, wheedle and turn a phrase to set the whole room alight with laughter. He wants success but the big break never comes, perhaps because he’s selling two-bit vacuum cleaners rather than something people really want. Elmer is smart and works out, when everyone is afraid of dying, it’s a captive market for salvation. With his seminary background, he’s a natural preacher and inveigles himself into the revivalist roadshow of Sister Sharon Falconer (Jean Simmons) which his force of personality shifts into a fire-and-brimstone exhibition of frenzied religious passion – just the sort of thing that gets the punters back into the church. But when the roadshow moves to the big city, will Gantry’s young affair with priest’s-daughter-turned-prostitute Lulu Baines (Shirley Jones) come back to bite him?

Elmer Gantry was seen as controversial and even outlandish at the time of its release – so much so a lengthy pre-credits opening crawl distances it from all those decent servants of the Lord who were worried it was tarring them with the same brush. But with TV evangelists raking in the cash and travelling preachers whipping crowds up into wild-eyed ecstasy, Elmer Gantry doesn’t seem so outlandish these days. Richard Brooks film adapts the middle-act only of Sinclair Lewis’ sharply satirical novel, and while it does smooth down the rough edges and offer touches of redemption for its charismatically selfish hero, it’s still a very entertaining plot-boiler with a well-delivered message and subtle character development.

Above all though it’s a defining star-vehicle for a perfectly cast, Oscar-winning, Burt Lancaster. Elmer Gantry plays to all his strengths: charismatic, larger-than-life and charming, overflowing with boundless energy and nimble, physical grace. Lancaster’s intense eyes and excitable grin burns through the screen and he’s totally believable as the sort of rogue everyone knows is a rogue but give him a pass because he’s so likeable. And he nails the magnetic charisma of fire-and-brimstone preaching, full of self-aggrandising comments about his own holy conversion from salesman to man of God. It helps that Lancaster’s physical prowess (at one point he does a body slide down the full length of the aisle mid-sermon) really helps build Gantry’s magnetic presence.

Elmer Gantry superpower isn’t that he’s shameless – he looks suitably guilty when calling his mother on Christmas day to explain, once again, he isn’t coming home – but that he can compartmentalise and forget shame so quickly. He manipulates and uses people with such charm they either don’t notice or don’t care – from charming clients on Christmas Eve with dirty stories to plugging Sister Sharon’s naïve assistant Sister Ruth (Patti Page) for details on Sharon’s life that he will then use to get his foot in the door of her roadshow. Even cynical journalist Jim Lefferts (Arthur Kennedy, warming up for effectively the same role in Lawrence of Arabia), who knows he’s a complete bastard, still finds him a great guy to hang out with.

But the truth is Gantry corrupts everything he touches. It happens by degrees, pushed along with winning arguments and eager ‘I’m just trying to help’ excitability, but its inevitable. Before he arrives, Sister Sharon’s roadshow is a dry but heartfelt and earnest mission focused on winning converts. Under Gantry’s influence it becomes religious entertainment. Because Gantry knows people need to have their passions stirred to really invest in something, and mesmerising patter is a huge part of that. Lancaster’s delivery of these showpiece sermons drip with eye-catching, inspiring passion – even when we know he’s a hypocritical bullshit artist who probably doesn’t truly believe word he’s saying, but sure does believe it in the moment. When even we feel stirred by it, is it a surprise his audiences start to get whipped into a frenzy, barking at devils and clawing across the floor to be saved by Gantry’s touch?

Sister Sharon’s manager and sponsor William Morgan (Dean Jagger skilfully playing a character who is far more susceptible to manipulation than he thinks) might have his doubts, but it works. Elmer Gantry takes a satirical swing at the Church as the reverends of the town of Zenith swiftly put aside any doubts (other than straight-shooter Garrison, inevitably played by Hugh Marlowe) and bring Sister Sharon’s Gantry-inspired roadshow into the big city to help drag more punters (and it’s quite clear that they see congregations as customers for religion) into their church. Elmer Gantry gets some subtle blows in on the commercialisation of the Church, even if it is careful to largely distance it as a whole from the tactics of Gantry.

Gantry’s corruption also touches Sister Sharon herself. Well-played by Jean Simmons, Sharon is earnest but surprisingly steely but as she lets a little of Gantry’s shallowness into her roadshow, so she starts to compromise on the very qualities that made her stand-out. From entering into a ‘good-cop-bad-cop’ performance for sinners to opening her heart to Gantry’s persistent seduction, Sharon becomes a portrait of corruption by degrees. Brooks’ film also implies in its dark finale that she has allowed herself to absorb Gantry’s spin that she could be a vessel of holy power, which puts her life at deadly risk.

Elmer Gantry is overlong and perhaps relies a little too much on Lancaster’s charisma – it fair to say when he is off-screen it’s energy lags. Its satiric edge is sometimes blunted by focusing on Gantry as the disease rather than a symptom of a church struggling to survive in a secular age. The introduction of Lulu Baines – an Oscar-winning Shirley Jones, playing against type as a bitter floozy – is a little late in-the-day and while her performance is solid enough, the character is more of a cipher in a plot-required final act conundrum than a fully-formed character.

But when the film focuses on Gantry, it’s a fascinating character study. How much does he believe in the things he says? Does he feel shame? How ambitious is he? When he says he loves Sharon, does he? Or does he feel everything he says in the moment, but it never sticks? Either way, it’s at the heart of Burt Lancaster’s compelling, charismatic performance which juggles a mountain of contradictions but never loses the sense of the shallow selfishness that lies behind the charm.