Coppola’s ambitious epic commits the cardinal sins – boring, hard to follow and immensely tedious

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Cast: Adam Driver (Cesar Catilina), Giancarlo Esposito (Mayor Franklyn Cicero), Nathalie Emmanuel (Julia Cicero), Aubrey Plaza (Wow Platinum), Shia LaBeouf (Clodio Pulcher), Jon Voight (Hamilton Crassus III), Laurence Fishburne (Fundi Romaine), Jason Schwartzman (Jason Zanderz), Kathryn Hunter (Teresa Cicero), Dustin Hoffman (Nush Berman), Talia Shire (Constance Crassus Catilina)

I wanted to like it. Honestly I did. I really respect that Coppola was so passionate about this dream project that he pumped $120 million of his own money into it to make it come true. You can’t deny the ambition about a film that remixes modern American and Ancient Roman history, within a sci-fi dystopia. But Megalopolis is a truly terrible film. Coppola wanted to return to the spirit of 1970s film-making: unfortunately what he’s produced is one of the era’s self-indulgent, overtly arty, unrestrained and pretentious auteur follies where an all-powerful director throws everything at the screen without ever thinking about whether the result is interesting or enjoyable.

In New Rome (basically New York), Cesar Catilina (Adam Driver) is a visionary architect and inventor, who created ‘megalon’, a sort of magic liquid metal. His vision is to use it make a glorious new Rome. He’s opposed by Mayor Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito) who wants to focus spend on practicalities rather than castles-in-the-sky. This leads to a series of increasingly dirty political flights between Catilina, Cicero and Catilina’s cousin Clodio Pulcher (Shia LaBeouf) the degenerately populist nephew of super-wealthy banker Crassus (Jon Voight), who is married to TV star and ambitious social climber (and Catiline’s former girlfriend) Wow Platinum (Aubrey Plaza). Catilina is also in a tentative relationship with Cicero’s daughter Julia (Nathalie Emmanuel). Or yes and he can mysteriously stop time. Somehow. Even he doesn’t know how.

The film is a sympathetic portrait of Catiline, a powerful Roman who (probably) caused a scandal by shagging a Vestal Virgin then attempted to mount a coup with a heavily pandering populist set of promises which led to his suicide (after defeat in battle) and his followers being executed by then-consul Cicero. Megalopolis’ version mixes this with elements of Caesar’s career and remixes Cicero, Claudius Pulcher and Crassus into versions of their historical forbears. It’s a neat idea, but it’s utterly bungled in delivery. Megalopolis is a film practically drowning in pretension, bombast and self-importance, its script stuffed with faux-philosophy and clumsy political points, its Roman history crude and obvious.

It feels pretty clear Megalopolis should be three to four hours and has been sliced down to two and a quarter. The problem is it feels like it goes on for four hours and practically the last thing I could imagine wanting as the credits roll was watching yet more of this nonsense. The most striking thing about Megalopolis is how boring it is (I nearly dropped off twice – and I was in an early evening showing). It hurtles through a series of impressive-looking-but-dramatically-empty set-pieces that often make no real narrative sense and carry very little emotional force. Characters are introduced with fanfare and then abruptly disappear (Dustin Hoffman’s fixer gets a big moment then literally has a building dropped on him) and the final forty minutes is so sliced down it loses all narrative sense.

Megalopolis feels like a bizarre art project, a collage of influences, opinions, concepts and inspirations, as if Coppola had been collecting ideas in a scrapbook for forty years and then put them all in. His heavily-penned script forces clunkingly artificial lines into its character mouths, frequently feeling like a chance to show off his reading list. Marcus Aureilus, Goethe, Rousseau and Shakespeare among others showily pop-up, alongside speeches from the real Cicero. Driver even does a (to be fair pretty good) rendition of Hamlet’s ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy, though it’s a sign of the film’s self-satisfied literariness that I can’t for the life of me work out why he launches into this at a press conference. Laurence Fishburne delivers the occasional narration with such poetic clarity, you almost forget it’s full of dull, gnomic rubbish, straining at adding depth to bland, fortune-cookie level statements.

It’s not just literary influences. The film is awash with pleased-with-itself cinematic references. Most obviously, Metropolis homages abound in its design, while Coppola’s breaking the film up with stone-carved chapter headings is a silent-film inspired touch. As well as Lang, there are clear nods-of-the-head to Abel Gance’s Napoleon (most obviously in its troika shots) while the smorgasbord of influences checks off everything from Ben-Hur to Vertigo to The Greatest Show on Earth (and damningly not as good as any of those, even DeMille’s clunker). All of this is combined with a wild mix of cross-fades, double exposures, sixties-style drug-induced fantasies and half a dozen other filmic techniques that are all very impressive but feel like a young buck looking to impress, rather than providing a coherent visual language for the film. Catiline’s time-stop abilities are some sort of clumsy stand-in for the powers of the film director – calling cut whenever he wants – but what we are supposed to make of the point of this in a film as randomly chaotic as this I have no idea.

The entire tone is all over the place. A scene of tragic maudlin grief will immediately be followed by sex farce. An attempted murder by a Buster Keaton inspired pratfall. A speech so overburdened with philosophical and literary allusions it practically strangles the person speaking it will lead into a joke about boners. The cast splits into two halves: one seems to have been told this is a serious film which requires deathly sombre, middle-distance-starring pontificating; the other half that they are making a flatulent satire. The random mix of acting styles has the worst possible effect: it makes those in the first camp seem portentous and dull; and those in the second like stars of an end-of-pier adult pantomime.

Driver makes a decent fist of holding this together, even if Catiline is an enigmatic, hard-to-understand character whose aims and motivations seem as much a mystery to Coppola as they do to the poor souls watching. But he can deliver a speech with conviction and seems comfortable mixing soul-searching with goofy dancing. Nathalie Emmanuel, though, is utterly constrained by taking the whole thing so painfully seriously that the life drains out of her. On the other side, Aubrey Plaza is the most enjoyable to watch by going for out-right-comedy as a vampish, power-hungry woman who uses her body to dominate men. Shia LaBeouf also goes so ludicrously overtop as a faithful version of the seriously weird Claudius Pulcher – he engages in cross-dressing, murder, incest and drums up crowds by quoting Trump and Mussolini – that it’s either daring or just as much of an unbearably self-satisified art project as the rest of the film depending on your taste.

But the main problem with Megalopolis is that its smug, pat-on-the-back, aren’t-I-clever artistic self-indulgence makes the film painfully slow and terrifically boring. How could a film that features riots, assassination attempts, orgies, murders, an actual meteor strike and magic time-stopping be as dull as this? When everything is thrown together without no emotional coherence whatever. Characters we don’t relate to or understand, who are either po-faced ciphers or flamboyant cartoons, stand around and quote literature at each other, while the director tries a host of flashy tricks he’s liked from other movies and never gives us an honest-to-God reason to give a single, solitary fuck about anything that’s actually happening at any point to anyone in the film.

It is perhaps the ultimate auteur folly. A director creating something that only appeals to him, at huge expense (and I suppose at least he paid for it himself rather than wrecking a studio) where no one was allowed to say at any point “this makes no sense” or “this is heavy-handed” or “this scene doesn’t mesh at all with the one before it”. Instead, it throws a thousand Coppola ideas at the screen, in a film designed to appeal to pretentious lovers of art-house cinema who like to tell themselves Heaven’s Gate is the greatest film ever made or the artform peaked with Melieres and it was all down-hill from there.

To approach the film in its own overblown style: whenever an auteur crafts, Jove plays dice with the Fates to decide on the cut of the cloth for Destiny’s Loom: should it come up sixes, the Muses smile, but should it be Snake Eyes, Pluto himself shall claim his due from those who would seize Promethean fire.

That makes as much sense as chunks of the film.

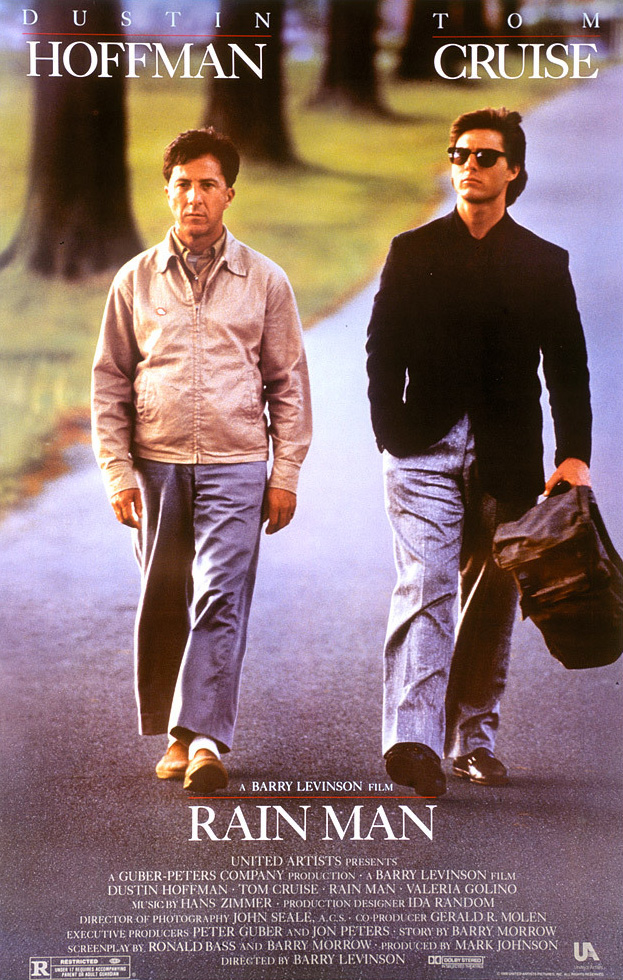

1988 wasn’t a vintage year at the Oscars, so perhaps that explains why this functional film ended up scooping several major awards (Picture, Director, Actor and Screenplay). Rain Man is by no means a bad film, just an average one that, for all its moments of subtlety and its avoidance of obvious answers, still wallows in clichés.

1988 wasn’t a vintage year at the Oscars, so perhaps that explains why this functional film ended up scooping several major awards (Picture, Director, Actor and Screenplay). Rain Man is by no means a bad film, just an average one that, for all its moments of subtlety and its avoidance of obvious answers, still wallows in clichés.