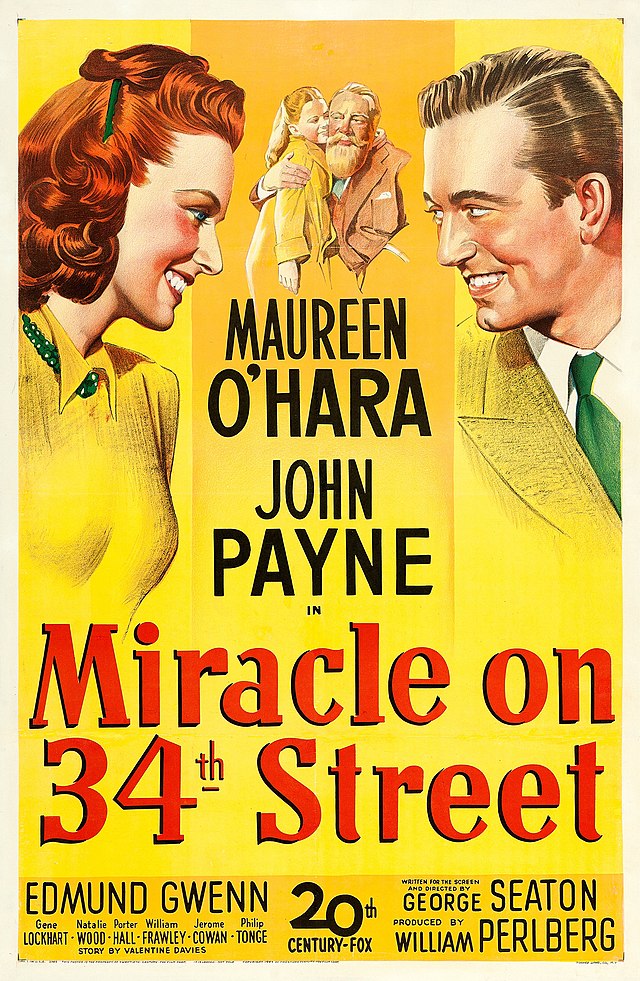

Warm Christmas fable will make you want to believe in Santa all over again

Director: George Seaton

Cast: Maureen O’Hara (Doris Walker), John Payne (Fred Gailey), Edmund Gwenn (Kris Kringle), Natalie Wood (Susan Walker), Gene Lockhart (Judge Henry X Harper), Porter Hall (Granville Sawyer), William Frawley (Charlie Halloran), Jerome Cowan (DA Thomas Mara), Philip Tonge (Julian Shellhammer), Henry Antrim (RH Macy), Thelma Ritter (Peter’s mother)

Santa Claus is a sweet little story we were told as kids, all part of buying into the magic of Christmas. How can we have been so silly as to think a jolly fat man with a red coat and flying reindeer delivered our Christmas presents? It’s the sort of fantasy adults are primed to burst like an over-inflated balloon. As a tribute to the earnest joy of believing in childish things, Miracle on 34th Street should also be the sort of thing the adult in us can’t wait to mock. Instead, its warmth and good-natured sweetness carries you along and makes you want to believe.

It’s the build-up to Christmas, and Macy’s in New York is working overtime to bring the magic to its customers (and turn a tidy profit). Macy’s Day Parade director Doris Walker (Maureen O’Hara) is relieved when Kris Kringle (Edmund Gwenn) takes the place of a drunken parade Santa and then occupies Santa’s Grotto in the store. Kringle is exactly the sort of guy you picture when you think of Santa – and, on top of that, claims to be Santa himself, much to the discomfort of Doris who doesn’t believe in all that stuff and certainly doesn’t want her daughter Susan (Natalie Wood) to. But when Kringle finds himself in court, fighting against being committed to an institution, with only Doris’ boyfriend Fred Gailey (John Payne) to defend him, can he prove there is a Santa Claus and it’s him?

Seaton’s film is an adorable delight which is funny and good-natured enough to avoid the trapdoor of sickly sentimentality. It’s a film about adults getting back in touch with the giddy delight of believing childish things. It flags up every cynical objection – and then gently suggests we’d be happier forgetting them. After all, what’s the harm in allowing ourselves in a few harmless flights of fancy – why should everything be measurable? Kris Kringle comes up against the hard-headed: harried mothers, businessmen, judges and lawyers and wins them over with his genuineness and warmth. He makes people want to believe – and doesn’t that, in a way, make him Santa?

It helps a huge amount that Edmund Gwenn is perfectly cast. Piling on the pounds and facial hair, Gwenn looks the part but also is the part. His performance is kind, considerate and bursting with warmth and good cheer. In a performance full of light, unforced playfulness, Gwenn gets the level of sweetness just right. A squeeze or two more and you would choke on the schmaltz of the whole conceit: but Gwenn is so adorable the audience wants to believe in him as much as the characters.

Especially as this Santa melts some of the cold commercialism of our modern Christmas. Miracle on 34th Street has a lot of good-natured fun at how Kris confounds the latent money-making of Christmas. On hire he’s instructed to memorise a list of preferred products to push on children. Instead he points mothers towards competing stores where they can get the exact gift they want or pick up better quality goods than at Macy’s. Of course, the concept proves so popular with customers that RH Macy is confounded by the goodwill it creates in his customers (and the huge sales it will lead to from their loyalty). Even other department stores start doing the same.

It’s one of the recurrent themes of the film: Kris brings out the best in people. Maybe not always for the right reasons: the shop-owners who want money, the judge who wants re-election. But it shows what benefit a little bit of good can have in the world. Kris also shows how little touches of consideration can change lives. There is a truly heart-warming moment where Kringle meets a Dutch orphan who simply wanted to meet Santa – although her adopted mother warned her Santa can’t speak Dutch. Much to her surprise, Kris launches into fluent Dutch, to the delight of the child. Miracle on 34 Street has several moments where the unstudied delight of children is captured to great effect, not least Natalie Wood’s delighted response to discovering the reality of Kringle’s beard (it also, to be fair, has several fairly cloying child actors).

Eventually the forces of darkness – led by Porter Hall’s twitch-laden store “psychologist”, whose bullying self-importance makes him the only person Kringle dislikes – insist we all put away childish things and chuck Kringle in an asylum. Miracle on 34th Street segues into a Capra-esque court-room drama (it’s hard not to detect touches of Mr Deeds Goes to Town) which pits Kringle’s home-spun honesty against legal cold professionalism. The clash becomes a delightful headache, as both the Judge and DA confront outraged children at home who can’t believe they are putting Santa on trial. It’s a great gag: who wants to be the judge who rules categorically Santa does not exist?

Alongside these gently amusing courtroom shenanigans (with John Payne doing an excellent job as Kris’ inventive lawyer) the film balances an endearing domestic plot. There is the inevitable will-they-won’t-they between Payne and O’Hara (if there is a bit of slack you need to cut the film today, it’s in Fred’s pushy wooing of Doris, including corralling Susan). But also, can O’Hara’s all-business professional, who’s raised her daughter with a Gradgrindish obsession with facts, melt her heart and allow both of them to believe a little bit? O’Hara handles this softening with all the consummate skill of a gifted light-comedian, while Gwenn’s delightful interaction with Wood’s precocious Susan, keen to access a world of imagination she’s never really known, is perfectly done.

it becomes a film about the power of believing. In our modern age we become expected to only base decisions on cold hard facts. Doris has taught her daughter to doubt imagination as a weakness to protect her from disappointment in the world (she is after all divorced, quite daring for a 40s family drama). But its also made Susan less likely to invest in faith, to open herself up to hopes and dreams. Its recapturing the ability to believe in something and be enriched by it that becomes one of the film’s richest messages.

It would be incredibly easy to poke fun at the good-natured naivety of Miracle on 34th Street, where businessmen are money-focused-but-decent and lawyers are amiably ready to indulge Kris with a smile. But it’s a film that zeroes in on an in-built nostalgia for simpler times in all of us. We’ve all been little Susan, sitting in a car desperately wanting to believe in the magical. It’s a film that demonstrates the eventual emptiness of cynicism, encouraging the audience to just put all that aside for 90 minutes and remember what it was like to be a child again. Throw in with that Edmund Gwenn as the definitive Santa and it might just be one of the greatest Christmas films ever made.